There has never been an arena built in Memphis with the same quality, better acoustics, TLC, and comfort as the Mid-South Coliseum.

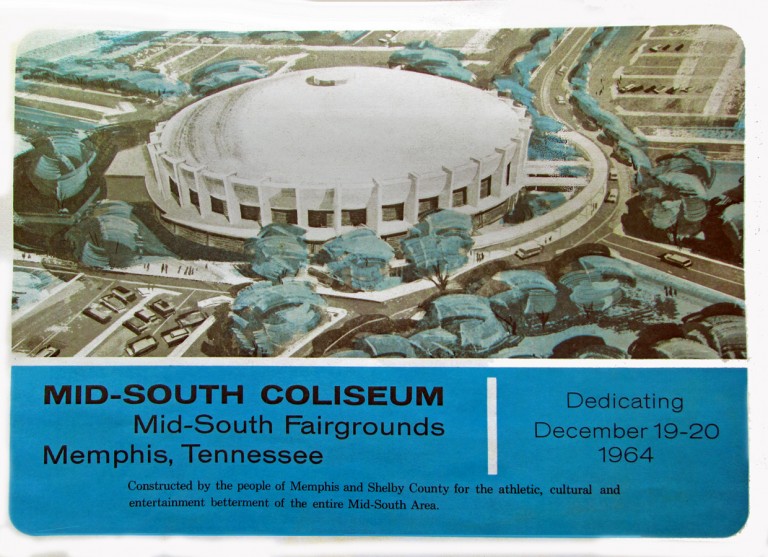

It was the culmination of a dream that began in the late 1950s for a new, all-purpose, “blue chip” public arena, and when the doors were thrown open in 1964, the building produced a burst of civic pride (building on the momentum created by the opening of the Roy Harrover-designed Memphis International Airport a year earlier) not seen again until the opening of AutoZone Park and FedExForum roughly four decades later.

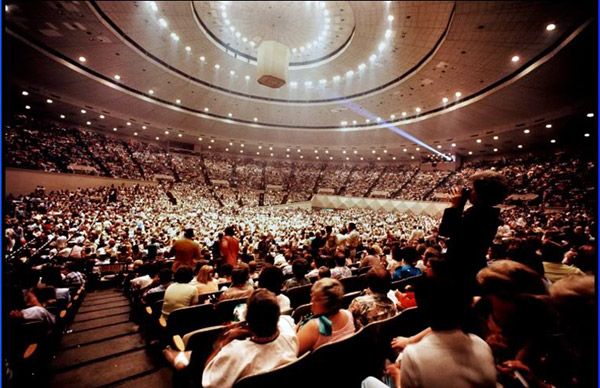

Anyone who bought a ticket for an event in the Coliseum’s early years remembers the terrazzo, the brick, the glazed ceramic tiles, the symmetry, easy access, lack of obstructions, and its overall comfort. It was impossible to imagine that another arena in the South could compete with it.

Although the building was similar to the coliseum arenas opened in 1960 in Jacksonville and in Mobile in 1965, it was markedly different in one respect: it was not planned as a segregated facility. Considering that Henry Loeb was serving his first term as mayor, and would later be immortalized for his infamous resistance to the unionization of Memphis’ sanitation workers which brought Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to the city, it is a historical irony that plans for the building were developed by the Loeb Administration and apparently always envisioned integrated audiences.

The Early Years

Multiple locations were evaluated by city-county planners for the Coliseum, including some outside Memphis, but in the end, the Fairgrounds was selected. City of Memphis and Shelby County, respectively paying 60% and 40% of the costs, selected Merrill G. Ehrman of Furbringer and Ehrman as lead architect with support from Robert Lee Hall & Associates. Before they even began architectural drawings, they toured recently built coliseum arenas, and when those visits were concluded, they proposed a coliseum structure for Memphis whose cost would ultimately be $4.7 million ($47.5 million in today’s money).

The Coliseum’s first event in October, 1964, was the Ringling Brothers Circus, and it was followed by its first stage show, the WDIA Goodwill Revue, which also was its first sell-out and set an attendance record that stood for years. In its 42-year history, the Coliseum was the go-to place for legendary concerts and Memphis State University basketball games, where the building design created a loud, dynamic sixth man for its teams.

In the Coliseum’s earliest years, the university had an all-White team, but when it integrated its team in the late 1960s with a single African American player and went to the Final Four in 1973 with a largely African American team, the city’s love of basketball was finally and irrevocably color blind. In addition, the building was home to Memphis Wings ice hockey team (it was mainly about waiting for the fights), the American Basketball Association (it was mainly about waiting for Dr. J to visit), and countless wrestling matches (which for some is remarkably what the building is remembered for).

An often forgotten footnote: the first NBA games played in Memphis were the eight “home” games in the Coliseum for the St. Louis (later Atlanta) Hawks.

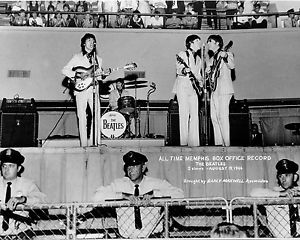

The good news was that the Coliseum opened in time for the British Invasion, with concerts by the Beatles, Rolling Stones, the Dave Clark Five (which sang less than 30 minutes which felt like its entire repertoire), Herman’s Hermits, Peter and Gordon, and Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders, but it also opened in time to become the hub for Memphis rock and roll and soul music with concerts featuring a young unknown singer named Otis Redding and Memphis music legends like Rufus and Carla Thomas, Booker T and the MGs, and more. There were also concerts by Memphis bands Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs, the Gentrys, and others.

Good and Bad

Essentially, every big name band, group, or singer found their way to the Coliseum, and the building earned a place in music history when the concert by the Beatles was credited with the reason they quit touring. We all know the story: coping with the controversy that erupted when John Lennon said the band was more popular than Jesus, the group decided to give up touring when two people threw a cherry bomb onto the stage in the evening concert and the Fab Four thought one of them had been shot. Then again, the incident had followed death threats, a Beatles record burning, city officials threatening to cancel the concert, Ku Klux Klan pickets, a Christian Youth Rally sponsored by 100 ministers at the same time as the concert, and John Lennon himself suggesting that the band not come to Memphis because of its violent tendencies.

For many, the pinnacle of the Coliseum’s history took place in four sold-out concerts by Elvis Presley over two days March 16-17, 1974, and three days later, when he performed one more sold-out concert in order to record an album for RCA.

If the music was the good news, basketball was the bad. In the first six seasons of Memphis State basketball, there was only one winning season. In fact, the dismal Moe Iba years included three years when there were 20 total victories and 56 losses for his “pass the ball around for five or six minutes and take a shot” teams. About the same time, the NBA games became a one-year phenomenon, and the American Basketball Association’s five years with three versions of the Memphis team – Pros, Tams, and Sounds – failed to capture the public’s interest even when Larry Finch and Larry Kenon were drafted.

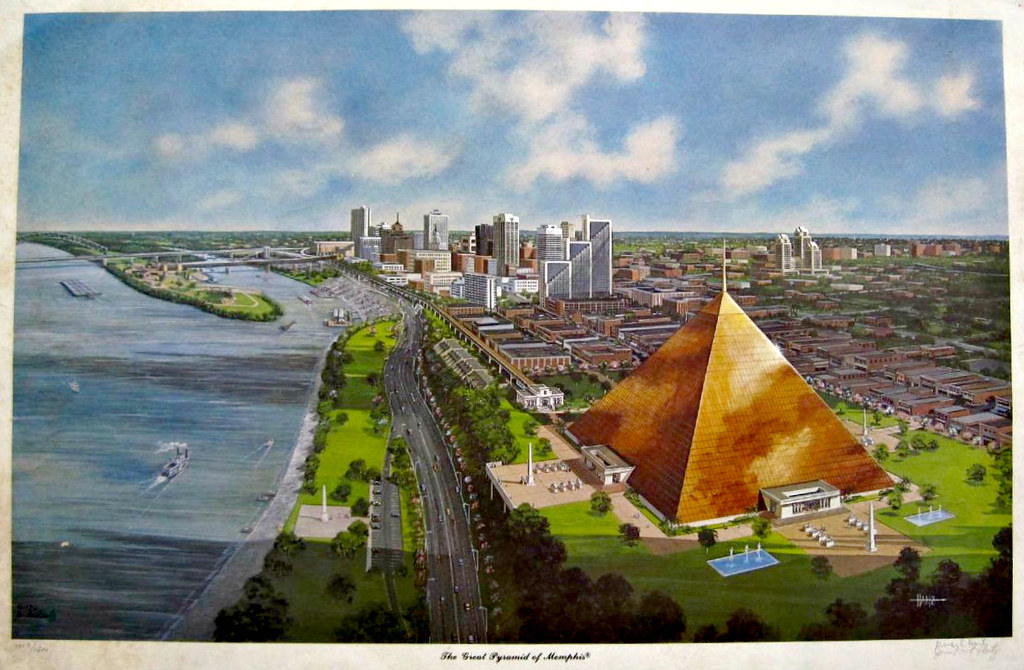

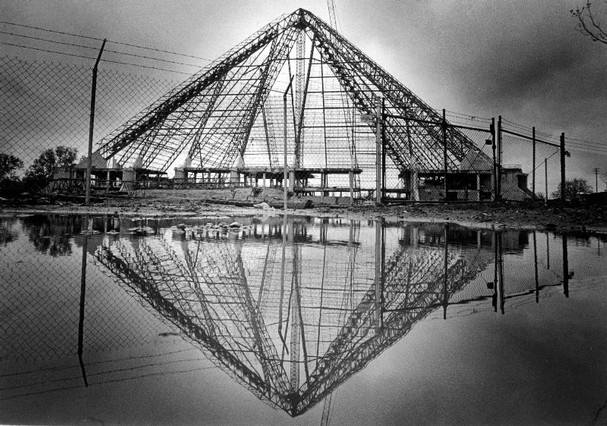

Eventually, the University of Memphis basketball program’s success and promoters’ complaints that they needed a bigger building produced pressure for a larger arena in the mid-1980s. Meanwhile, the idea of a large pyramid being built as an icon for Memphis had been around for decades, and at one point, it had even been suggested for Shelby Farms Park and at another time, as part of a domed Fairgrounds plan by Memphis architect O.T. Marshall.

Building An Icon To Get A Downtown Arena

The full court press for a new arena and the desire for a city icon converged in the late 1980s. Government officials who wanted the new arena downtown – which produced an outcry for people more accustomed the midtown location – were captivated by a golden pyramid on the South Bluffs drawn up by Mark Hartz. They made the argument that it should be downtown on the riverfront where it would be seen by the most numbers of people. There had been a brief discussion about “raising the roof” of the Coliseum, but because of the way the building was constructed, it was not practical or cost effective for it to provide the increased number of seats envisioned.

Once the downtown location won out politically (it was always a contentious decision with the public which, in a poll years after it opened, were still split 50-50 on the question of whether it should have been built downtown) the question was whether it should be built on the south bluffs or where it is located today. It seemed clear that the south bluffs location would be more prominent, but the Auction and Front Street address was chosen after Memphis developer Henry Turley and architect Tony Bologna convinced key leaders that the south bluffs were prime for residential development and that handling the parking demand there would be difficult. In support of their position, they made a film of the drive down Riverside Drive that showed that the pyramid would be largely invisible for motorists driving down that highway because it was on the bluffs above them.

As a result, the current Auction and Riverside location was chosen although Shelby County Commissioner Vasco Smith said it felt to him like a “voodoo site where something bad had happened.” Fortunately, for Memphis, Mr. Turley and Mr. Bologna’s vision of the south bluff’s development has come to fruition, which would not have been possible if The Pyramid had dominated that part of downtown.

More Pyramid history: Looking Back At Sidney Shlenker And The Pyramid, Part 1 and Part 2

It was thought by city and county officials that with the opening of the Pyramid Arena, the Coliseum would close, and in preparation for the day, city and county governments offered the building at no cost to University of Memphis for women’s basketball and special events, but the university declined out of concern about maintenance costs and deferred maintenance and capital improvements.

A Battle It Could Not Win

But the closing of the Coliseum was not to be.

When city and county mayors told the Coliseum board members to close the building, they refused to comply (although they had been appointed by the mayors). Instead, the board members essentially declared war, deciding to keep the Coliseum open and use the substantial balances in the building’s bank accounts to do it. However, the Coliseum needed $10-15 million in renovations and upgrades, but when the uncooperative board asked city and county mayors for the money, it was an easy answer: the mayors said no.

The sides hardened even more when the Coliseum Board, in an effort to prevent city and county governments from tearing down the building, filed a successful application in 2000 to place the building on the National Register of Historic Places. The application sealed the fate of the building, because while the city and county governments could not close the Coliseum over the wishes of the board, they could refuse any funding while the board depleted its bank accounts.

The decision by the “runaway board” essentially cost Memphis and Shelby County taxpayers tens of millions of dollars because to stay open successfully, the Coliseum had to become a competitor to the Pyramid, driving down rental rates and revenues at the new arena, creating deficits approaching $2 million a year that had to be paid by city and county.

Despite public perceptions, The Pyramid was not making big profits from the University of Memphis basketball season. In exchange for the university’s contribution of about $15 million to the building construction budget, it received a sweetheart deal that meant that its entire year of basketball produced less revenue for The Pyramid than a single sold-out concert.

Despite its board best efforts, with the opening of the Pyramid in 1991, the Coliseum began a slow descent into obsolescence. Most marquee acts were playing The Pyramid, and even if they didn’t, it was because the Coliseum had undercut the promoters’ costs there, which meant that the Coliseum was settling for less and sinking into the red with its operating budgets – $400,000 in losses in its last year.

**

Part 2 will be published Wednesday, April 3, 2024

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.