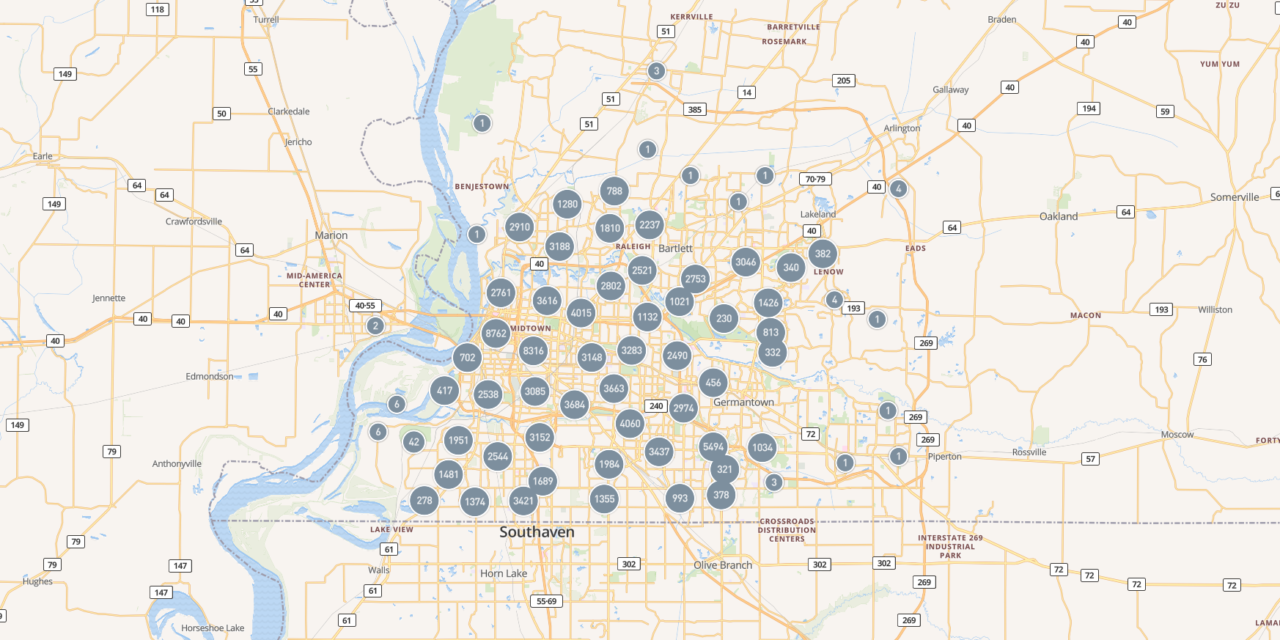

Map: Memphis Crime Last 12 months: numbers represent charges

If we knew the answers, we wouldn’t have the problem.

That truism is especially accurate when applied to the problem of violent crime.

It’s why Mayor-elect Paul Young’s reaction to the recent murder of a St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital was concerning: He promised to get with local law enforcement officers and community leaders to discuss a plan on moving ahead. It’s the approach often used in Memphis with the same people discussing the same ideas with the same results. Instead, his new administration needs to take new approaches, consider new ideas, and access new intellectual capital.

In the meantime, Republican State Senator Brent Taylor asked Governor Bill Lee for state government’s help in dealing with crime in Memphis, but it is a terrible idea on some many levels. First, state politicians never fail to inject their reactionary politics into everything they touch and Memphis has no need for that overlay while searching for actual answers. Second, asking state politicians for help is like asking the arsonist for advice on firefighting. After all, it is their “guns here, guns there, guns everywhere” simplistic gun laws that have intensified violent crime in Memphis and increased the risks for police officers patrolling city streets.

That’s not to say that we’ll find the answers talking to the usual suspects and expecting the innovations that are needed. It’s hard to remember how many summits we have had since Mayor Jim Strickland defeated AC Wharton right years ago by promising to get crime under control.

Summit after Summit

Just two months ago, Attorney General Steve Mulroy hosted state and local officials in a closed-door “summit” to improve communications and reach general consensus on ways to improve crimefighting. It’s hard to point to any solutions that flowed from it.

In March, yet another “crime summit” was held with City Council members, Memphis Police Department, Mr. Mulroy, state lawmakers, and school leaders. It was heavy with talking points and light on new ways to fight crime. While the summit was actually under way, two Memphis police officers were shot while responding to an armed person call.

In January, the Memphis Shelby Crime Commission held a summit that called for more resources, partnerships, and paradigm shifts in addressing the problem of youths involved in crime. We had heard it all before. In June of last year, the United States Attorney’s office, along with an array of north Memphis leaders, conducted the third “Better Community Summit” to reduce violent crime.

In February of last year, the Crime Commission released another five-year “Safe Community Action Plan” and more than anything, it suggested that the organization had outlived its usefulness in the face of violent crime skyrocketing since 2016.

In November, 2021, the Crime Commission and the Greater Memphis Chamber held a “crime summit.” It was attended by the usual suspects with the usual talking points.

2016: A Landmark Year

Speaking of 2016, that was the year that Mr. Strickland was elected mayor and Bill Gibbons became head of the Crime Commission and University of Memphis Public Safety Institute. Today, the violent crime rate is 43% higher and property crimes have risen by 58%.

This year, Memphis is expected to reach its highest crime rate since the Crime Commission was created in 1997.

To repeat, if Memphis had the answer, it wouldn’t have the problem.

So, here’s hoping that Mr. Young’s answer to crime prevention is not to have a summit or to meet with the usual suspects but to think outside the box. In doing that, he could take a lesson in the creation of the Crime Commission in 1997.

The Crime Commission only exists because of the persistence and leadership of the late Ira Lipman, founder of Guardsmark and a pioneer in the private security industry. He was successful in pushing the city and county mayors to support his idea for a think tank that would report on trends in crime prevention, track what other cities were doing that were successful, and recommending innovations to reduce crime.

An Early Lesson: Increase Intellectual Firepower

To that end, he hired two national criminology experts to advise and set things in motion and in the early years, they would test ideas and push the envelope in a city where too many people went along to get along. At the time, the Crime Commission’s pledge was to make Memphis-Shelby County one of the safest communities of its size in the nation by 2011.”

By that year, the overall crime rate, the major violent crime rate, and the major property crime rate had all decreased. Today, 12 years after that date, the goal has been left in the dust.

It’s obvious that all the Crime Commission’s grand safe community plans over the years – rinse and repeat – and redundant summits have not worked, and yet, for the past decade or so, the answer of reducing crime has been for too many people is to gather the same people to discuss the same issues with the same results – crime goes up. It’s worse than the well-known definition of insanity because people are getting killed, the lives of families are disrupted, new types of crimes like carjackings have proliferated, and Memphians who have never questioned living in the city are talking about moving out.

In large part, we have persisted in old school policies and strategies when other cities have tried innovative ideas, such as taking a public health approach that disaggregates the responsibilities of police so they aren’t in situations where mental health professionals would be better suited; PSTs to handle all traffic accidents and other reports that should not require a commissioned officer; community street teams trained as mentors and interventionists; targeting drag racing and carjackings; credible messenger interventions, restorative justice, and other strategies to create an ecosystem of prevention.

Systemic Change for Systemic Results

But Memphis also needs systems change.

First, it should create the Memphis Office of Violence Prevention. It should be modeled after similar agencies in other cities like Providence and Newark where this approach has made a difference in implementing a new culture of prevention and an actual ecosystem to drive it. It should resist conventional wisdom about crime, it should loudly advocate for better ways to fight crime and for smarter gun laws, and it should coordinate services in hopes of bringing promising programs to scale.

Second, the Crime Commission should be disbanded or reorganized. The circular relationship it has with the UM Institute of Public Safety is not serving the community’s best interest. It’s not uncommon for the work of the Public Safety Institute headed by Bill Gibbons to produce recommendations of the Crime Commission headed also by Bill Gibbons and when the Crime Commission recommendations are adopted by city government, their effectiveness is validated aby the Public Safety Institute where they originated in the first place.

The Crime Commission’s main role these days seems to be producing regular reports about crime data which are public information and available in other places. What Memphis needs is a serious data hub where policies are objectively evaluated and where police data is broken down by race/ethnicity/general to identify racial disparities, mental health cases, arrests by types of crime, solve rates, use of forces cases, recidivism, incarceration rates, bail bonds, and key indicators of the effectiveness of the criminal justice system such as criminal court caseload, time to disposition of a charge, etc. Despite Senator Taylor’s largely political request to Governor Lee, this is data that we already have; we just need a reliable system where they are posted.

Creating the Data Hub We Want and Need

And if we’re really serious about having a data hub that can illuminate and drive policy, it should include indicators that provide an even broader context for considered crime prevention strategies: economic independence, affordable child care, housing conditions, mental health and physical health, schools, and other data that allow us to determine the effectiveness of whatever plan is developed and adopted by the Young Administration.

As the mayor of St. Louis, Tishaura O. Jones said after her election two years ago, it’s about “putting the public back in public safety.” Meanwhile, by September, the number of murders in St. Louis has decreased by about 22%. That said, murders in Baltimore fell 22%, New Orleans 24%, Milwaukee 24%, Detroit 10%, and Nashville 4%. Memphis? Homicide rate up 77%.

Leadership Matters

It does not mean these cities are not still deeply concerned about violent crime but there is proof that leadership matters.

Leadership matters, as other cities have proven with mayors who take fresh looks at the inefficient, ineffective systems that result from neighborhood disinvestment, poor mental health services, low officer morale, and strained relations between community and police.

As Mayor Jones said in her Platform for Public Safety: “The city must reject the false choice between being ‘tough’ on crime and addressing the root causes of violence. We must address the small groups responsible for the large percentage of violent crimes. Officers are spending too much time responding to routine calls instead of addressing violent crime. We must invest in resources that will actually make us safer, such as treatment for substance abuse and mental health disorders, programs that lift people out of poverty, and meaningful criminal justice reforms.”

The End of Doing the Same and Expecting Different Results

Mayor Jones began by declaring that gun violence was a public health crisis and emulated the national model of Focused Deterrence and the Community-First Approach to Public Safety in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Meanwhile, in Newark, the number of murders, robberies, aggravated assaults, burglaries, and theft from autos are all down as the mayor’s office and Rutgers-Newark School of Criminal Justice developed the Newark Public Safety Collaborative. It offers an alternative to traditional police-centric models, it makes data analytics and research accessible to change agents, and emphasizes place-based predictive analytics.

In these cities and others, their leaders recognize the truth in the adage, if we knew the answer, we wouldn’t have the problem. And that’s where Mr. Young can show real leadership, reaching out to his mayoral colleagues for advice and answers, by increasing intellectual capital brought to bear on these issues, and by understanding that what we have been doing has not worked.

If there’s to be another summit, it can’t be like the ones that have gone before. What’s needed now is an evidence-based summit of national experts and innovators, mayors from cities where policies have reduced crime, researchers and academicians, heads of reform movements, intervention groups like Geoffrey Canada’s Harlem Children’s Zone or Father Greg Boy’s Homebody Industries, and others.

It’s way past time to admit that the definition of insanity applies to too much of what has gone on in Memphis crimefighting plans – doing the same thing and expecting different results.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

I’m about one, post summit, “We have a crime crisis right now and it requires an all hands on deck approach to tackle the problem”, statement away from putting the house on the market. Do local “leaders” honestly think people who have a choice are willing to just live with this issue?