All the talk about the new Ford plant northeast of Memphis reminds me of when I worked in the old one.

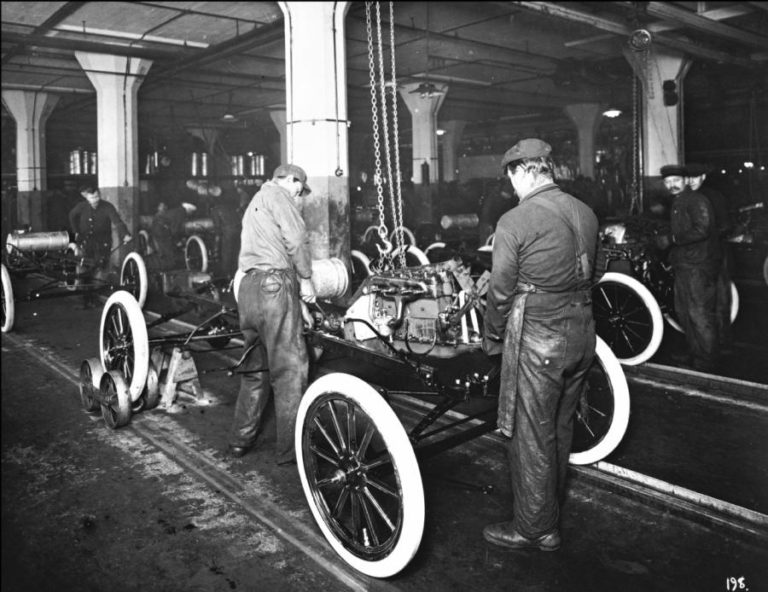

It was a “branch assembly plant.” Built in 1913 at a cost of $150,000, it was a gritty, no-frills box of a building. Five stories, 200,000 square feet. Auto parts were delivered to the fifth floor and the assembly took place as they moved down through the floors until a Model T emerged in the showroom on the first floor or was shipped to a dealership in the region.

It was one of about 30 similar plants built in major cities around the U.S. on the theory that they would reduce the delivery costs for the company by transporting the popular cars shorter distances.

By 1924, the Memphis Model T Plant was obsolete. The multi-floor assembly plant gave way to an expansive one floor assembly line. Ford closed the building and relocated to a 400,000 square foot plant at Riverside Drive and South Parkways.

By 1924, the Memphis Model T Plant was obsolete. The multi-floor assembly plant gave way to an expansive one floor assembly line. Ford closed the building and relocated to a 400,000 square foot plant at Riverside Drive and South Parkways.

From Assembling Cars to Assembling Newspapers

In 1932, the old Ford plant was sold and became home to the Memphis Press-Scimitar and The Commercial Appeal. Their circulation extended from the Delta to the Missouri Bootheel.

But that was years before I got there in 1970 to take a reporter’s job at the Memphis Press-Scimitar. It had a circulation of 150,000 and a subscription cost $1.95 a month. The building still had the feel of a old Ford plant and we never forgot it as soot still sifted from the ceiling decades after the last Model T had rolled off the assembly line.

The Ford assembly plant that was reincarnated into a newspaper assembly plant was located at 495 Union between the vibrant downtown to the west and an artery clogged with automobile dealers and hospitals to the east.

The large box that was the Ford building remained: basic with no frills (except for editors’ offices). The first floor was the lobby, the second was for business services, the third was for The Commercial Appeal, the fourth floor was for the printing presses, and the fifth and top floor was for Memphis Press-Scimitar.

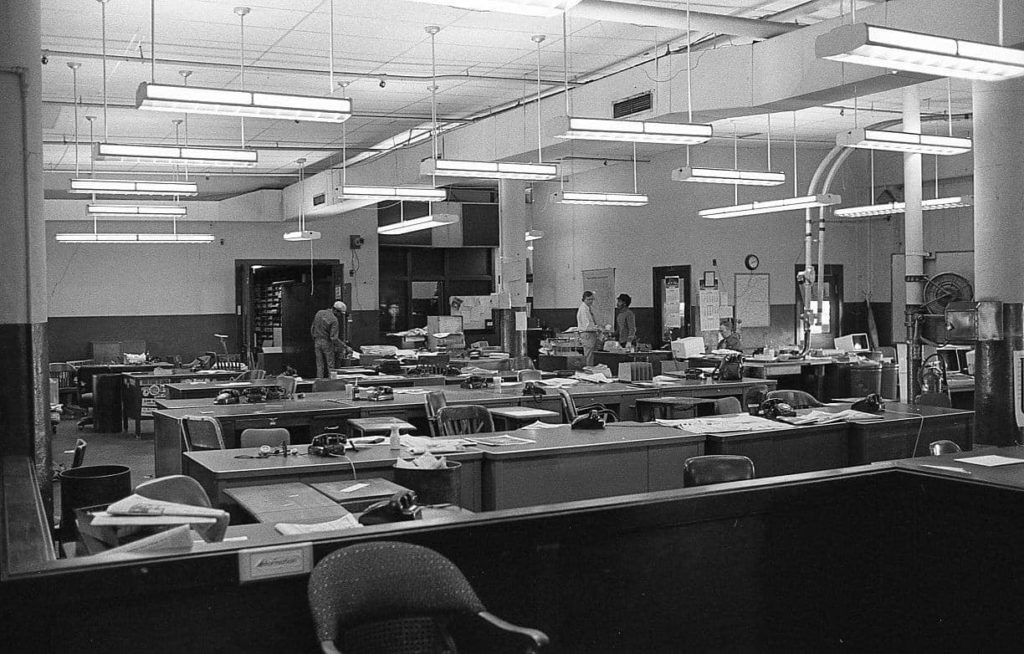

On the newspaper floors, dozens and dozens of desks were pushed head-to-head with the cacophony of reporters talking over each other as they called sources, took information from callers, and transcribed stories dictated by reporters at news events outside the building. The rhythmic sound of dozens of typewriters was constant and somehow reassuring. Stories were edited on the copy desk next to the windows facing downtown whose superior view was tempered by extremely hot summer days.

One Of A Kind

It was a different time and a world away from today’s daily newspapers (or what’s left of them).

The newspaper floors were a time capsule. They looked essentially like newsrooms from 30 years earlier in one of the classic black and white movies set in newspapers in the Thirties and Forties. And it was populated by an eclectic group of characters and eccentrics that no screenwriter could fathom.

There was the “ding, ding, ding” when news bulletins came over the teletypes. There were switchboards, classified ad salespeople, typesetters, typewriters, paper boys, letterpress printing, and hot type. When the presses rolled, the whole building shook. Radiators hissed, there were 16 feet ceilings and floors were 16 inches thick, and the elevator used most often by employees often didn’t make it to the top floor. There, the word “colored” had been covered up but could still be read on the restrooms.

There was the “ding, ding, ding” when news bulletins came over the teletypes. There were switchboards, classified ad salespeople, typesetters, typewriters, paper boys, letterpress printing, and hot type. When the presses rolled, the whole building shook. Radiators hissed, there were 16 feet ceilings and floors were 16 inches thick, and the elevator used most often by employees often didn’t make it to the top floor. There, the word “colored” had been covered up but could still be read on the restrooms.

The paper in the bathroom was newsprint on which we also typed our stories. The air was often thick with cigarette and pipe smoke and the smell of alcohol sometimes wafted through sections of the newsrooms. After being edited on the copy desk, news stories were sent by pneumatic tubes to the press room where type was set and turned into aluminum plates for the presses which shook the building when they ran. There were visits from politicians and celebrities and blasé reporters barely gave them a second look. The place hummed with activity, and there was always the air of expectation that something exciting was about to happen and that any day could produce another hilarious anecdote repeated time and time again. Like the time Eldon Roark, an avid and tournament-winning tennis player wrote a headline printed in one edition before it was corrected that the new tennis center on Southern Avenue had good courts but were really hard on the balls.

Once Upon A Time

Six beat reporters downtown had their own offices and I was one of them, sending in my stories in the beginning by teletype from my third floor corner Courthouse office. It was such a simpler time that I was given a key to the building in case I ever needed to get in after hours. Later, downtown reporters’ teletypes gave way to a newfangled toy, a first generation fax. Reporters clipped their news stories onto a roller which spun rapidly and accompanied by a shrill sound once the phone on the other end answered and until a copy of the story was received at the news desk.

Reporters at the Press-Scimitar seemed to always be staring down a deadline. They was one at 7:30 a.m. for the edition that went outside Shelby County, another at 11:30 a.m. for the edition delivered to home subscribers, and finally, one at 2 p.m. for the newspaper boxes and the “news boys” on street corners.

There was the movie and book critic who put the books he didn’t want outside his office and rarely deigned to speak with rank-and-file reporters; a columnist who could arrive at work inebriated but who could always turn out his copy without difficulties; the elderly reporter who had never done anything much but write obituaries; the sports department with people like George Lapides, George Bugbee, Ken Jones, and Bobby Phillips; an editor who cared more about the society page than other sections of the paper and on the rare occasion he appeared in the newsroom, we knew he must be lost.

There was the movie and book critic who put the books he didn’t want outside his office and rarely deigned to speak with rank-and-file reporters; a columnist who could arrive at work inebriated but who could always turn out his copy without difficulties; the elderly reporter who had never done anything much but write obituaries; the sports department with people like George Lapides, George Bugbee, Ken Jones, and Bobby Phillips; an editor who cared more about the society page than other sections of the paper and on the rare occasion he appeared in the newsroom, we knew he must be lost.

The morgue was headed up by a small man who organized countless newspaper clippings, reporters’ notes, almanacs and reference books, and more. It appeared to be a room of chaos to everyone else but he and his assistant delivered information to a reporter on a specific subject in short order. Like almost everyone else in the newsroom, he was a character. He was once asked for a file on Muslims and when it wasn’t forthcoming, the reporter went back to the morgue and said, “Do you have the file on Islam yet?” “Make up your mind,” he retorted.

The Cast Of Characters

The “slot” with the city editors and editing staff was west of the reporters’ desks with a great view of downtown. One masterful editor could take a three-paragraph story, edit it, and return it reduced to three sentences.

Managing editor Ed Ray was the embodiment of an old school newsman. He was gruff with a soft side. He began as a sports reporter when he was 14 years old, he was sports editor at 19, and was a managing editor by the time he was 24 years old. He was an old school newspaperman and impossible not to respect.

City Hall reporter Clark Porteous had covered the Emmett Till trial in Mississippi where he was praised by his African American colleagues as a reliable liaison for them with prosecutors and law enforcement; the trial was seven years after, as a Neiman fellow, he had written a novel about a lynching in Mississippi. Susan Adler Thorp would join him in covering City Hall and the formidable pair had an uncanny knowledge about the building’s behind-the-scenes political machinations. Kay Pittman Black, covering federal courts, came from a prominent Biloxi family and had covered the civil rights movement where she had such good sources that she was shadowed by the FBI and Memphis Police Department who spread rumors aimed at diminishing her effectiveness to get the truth from the street into print.

Roy Hamilton covered courts and moved to county government when I was assigned to courts; his purple prose was featured in stories he wrote for true crime magazines under the name of Roger Hemingway. Police reporter Menno Duerksen for UPI covered the Nuremberg Nazi Trials and had dodged bullets reporting on the creation of the State of Israel before coming to Memphis where frustration with an editor once led him to throw his typewriter out his police station office window onto Second Street. Ed Topp was an editorial writer and member of a prominent, first family of Memphis whose ruins of the family mansion was deteriorating on Beale Street across the street from the paper where its shell was occasionally a place for reporters’ lunches.

Michael Donahue was the most likeable copy clerk in history and would rise to become a reporter who seems to know everyone in Memphis arts, entertainment, and culture. Mr. Roark and Robert Johnson had their fingers on the pulse of the city and turned out columns day after day after day. A reporter was taking down information about a traffic fatality when he realized the victim was his mother. An obit reporter called a husband to get the vitals about his wife only to learn he hadn’t been told that she had died.

It was a very White reporting group with only one Black reporter, which sadly reflected newspapers across the U.S. at the time. Crisis erupted when the person selected for the yearly “Teenager of the Year” award was African American.

At its height, about 1,500 people worked in the newspaper assembly plant at 495 Union. The Press-Scimitar would be closed by Scripps-Howard in 1983 after its circulation had dropped to 80,000 – a circulation either of today’s Memphis daily newspapers would covet.

The Real Newspaper

The old Ford plant was demolished in 1978 and its modern architectural replacement, according to former Commercial Appeal reporter Jimmie Covington, felt “more like an insurance company.” “The old building was the real newspaper,” he said. Meanwhile, the electrified American flag atop the building with its 45 stars was moved to the top of the press box at what was then called Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium.

Former reporters who worked in the old Ford plant are scattered across the country now. Most of the surviving ones are in their late 60s and 70s and their vivid memories of the old Ford plant and the way newspapers used to be could fill several books with their anecdotes.

Susan Adler Thorp, once a reporter at the Press-Scimitar, repeats a favorite:

“A man without a shirt on the press floor started banging a pipe on the presses. Someone called the psychiatric hospital and men in white coats charged out of the elevator on the fifth floor. They were carrying a strait jacket and said to (columnist) Bob Johnson, ‘we understand someone here has lost their mind.’ Bob turned in his chair and waved his hand toward the newsroom and said: ‘Take your pick.’”

*****

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

Incredible narrative. The change in the physical relationship between the old and new building and the city and how it reflected or foretold the evolution of the newspapers themselves is particularly poignant.