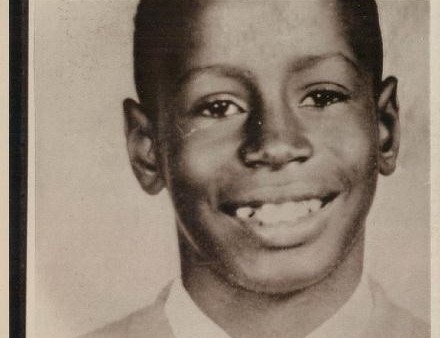

Smart City Memphis remembers the death of teenager Elton Hayes 50 years ago, the trial, and the aftermath.

Part I today: The Introduction to a Teenager’s Murder

Next is Part II: The Incident; Part III: The Trial; and Part IV: The Outcome and Aftermath

**

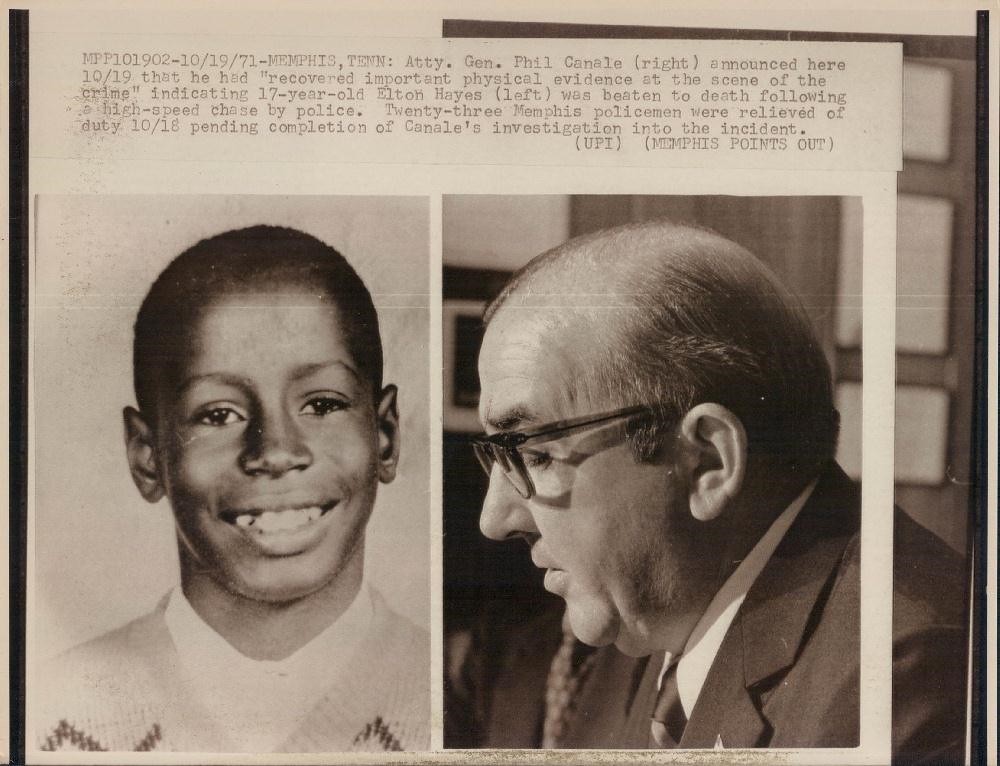

It was 50 years ago today that 17-year-old Elton Hayes was beaten to death in a ditch outside Memphis by law officers after a high-speed chase.

Their initial report claimed he died of a traffic accident but that explanation was shattered when it became obvious that he died from blows to his head.

His death three and a half years after the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. punctured the prevailing rhetoric of the time about a new racial understanding and reconciliation by Chamber officials, politicians, and civic leaders.

The African American teenager’s death took place on an isolated country road and it would rock the community. His death intensified questions about the state of race relations here, because unlike the assassination, his killing could not be blamed on an outsider. Instead, it had been carried out by Memphis policemen and sheriff’s deputies paid to protect the community.

The broken body and shattered skull of the bloodied African American teenager was unmistakable proof that under a veneer of progress, racism still thrived. His death set off days of protest, sometimes violent, that underscored the seminal fact: Black Memphians had reached a point of no return and they would not ignore the police brutality that had become a regular part of their lives.

When Elton Hayes died, Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb was in the last two and a half months of his turbulent term in office, forever linked with the incalcitrant politics that brought Dr. King to Memphis to defend the rights of city sanitation workers and led to the civil rights leader’s murder. It was a time when the Memphis’ population was almost 40% Black but only three of the 13 members of newly created Memphis City Council were African Americans – Rev. James Netters, Fred Davis, and J.O. Patterson Jr.

When Criminal Court Judge Otis Higgs Jr., the only Black criminal court judge in Tennessee, was selected to preside over the trial of the lawmen charged in Mr. Hayes’ death, it not seen as mere coincidence but as an act intended to defuse the racially-charged emotions surrounding the trial.

Elton Hayes’ life was taken from him in the early hours of October 15, 1971. His death became a watershed event in the history of modern Memphis and Shelby County. It is often overlooked today although it is a case study of how the system, even when it appears to be aimed at justice, may be orchestrated to deny justice.

The bitter seeds of discontent that followed the verdict by the all-white jury provoked a blunt and volatile debate about how to create a just community. It’s a discussion that continues today so many decades later.

Elton Hayes would now have been 67 years old.

Beginning today on this blog, I’ll remember the teenager, the impact his killing had on Memphis and Shelby County, and how ultimately no one was held accountable.

**

The first journalist who knew 17-year-old Elton Hayes had been murdered October 15, 1971, by law enforcement officers was Susan Adler Thorp, a Memphis Press-Scimitar reporter and recent graduate of the University of Missouri assigned to write obits on the day of the teenager’s death.

At 5:30 a.m., shortly before she made her calls to area emergency rooms to learn about any overnight deaths, law officers had brought Hayes’ body to John Gaston Hospital at 5:30 a.m. Doctors and nurses were told that he died when he was “thrown from a truck,” the police report stated.

As part of the obituary writer’s routine, Ms. Thorp called John Gaston Hospital. A nurse answering the telephone at John Gaston Hospital gave her the name of Elton Hayes and lowered her voice, saying she had never seen the kind of injuries he suffered from a traffic wreck.

The nurse said it looked more like he had been beaten to death, and Mrs. Thorp dutifully forwarded the information to the Press-Scimitar city desk which forwarded the information to the reporter on the police beat. The beat reporter was a fixture at the Memphis Police Department and was favored by the men in blue for his sympathetic coverage of all things MPD. As usual, he accepted the explanation by police officials about Mr. Hayes’ injuries.

Three days later, The Commercial Appeal broke the story, sparking furious outrage about the incident and the failed cover up. Five days of protests and scattered violence ensued.

In Orange Mound, where Mr. Hayes lived, there were reports of rock throwing, fire bombings, and vandalism. Post Group News reported: “Memphis was pushed to the edge of riots, with unrest seething in every segment of the African-American community. In Orange Mound where Hayes lived, there were reports of rock throwing, fire bombings and vandalism. Students left schools in large numbers and congregated on Park Avenue to vent their frustrations and grief. After several reports of students throwing rocks and bottles at passing cars, police cut off traffic between Pendleton and Hanley and ordered in helicopters. Mayor Henry Loeb declared a citywide curfew from 7 p.m. to 5 a.m.”

The headline in the October, 1971, issue of The Black Panther read: “MEMPHIS IGNITES: “NOBODY WAS HURT UNTIL THE POLICE OFFICERS GOT THERE.” It was accompanied by photographs of Mr. Hayes in his casket. At his October 19 funeral, his face was so swollen and distorted his family said it was hard for them to recognize him.

The Shelby County Medical Examiner ultimately ruled that Mr. Hayes died from multiple blows to the head that bruised his brain and caused a hemorrhage, blowing apart police claims that he died as a result of a traffic fatality.

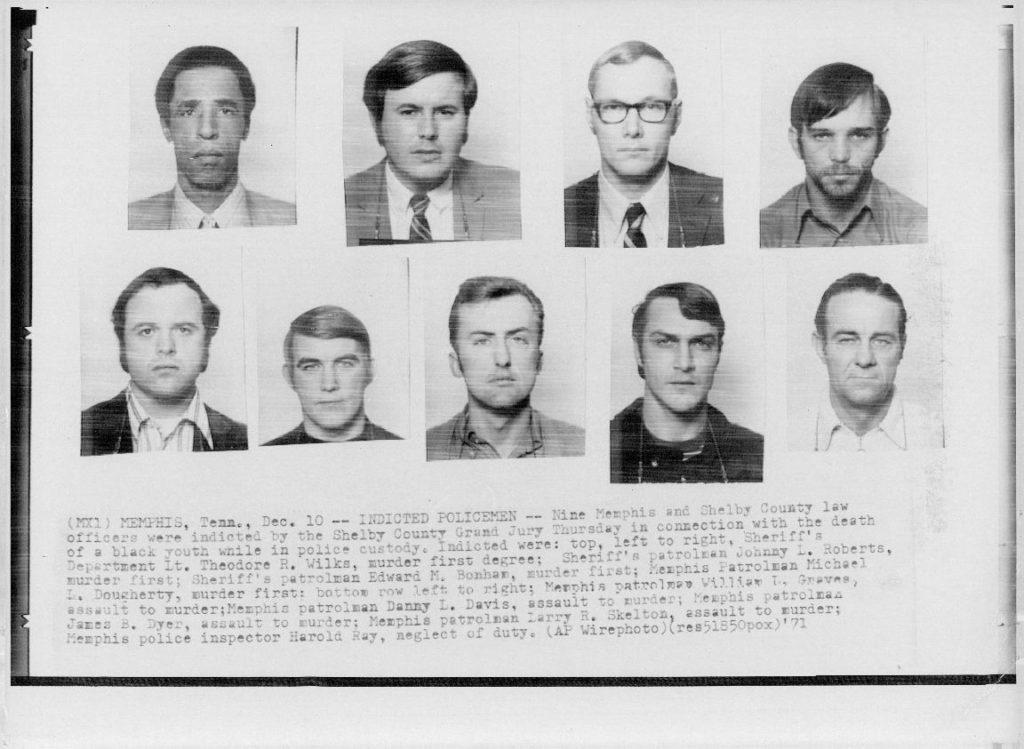

About seven weeks after the incident, on December 9, 1971, indictments were returned by the Shelby County Grand Jury’s nine White and three African American members.

About seven weeks after the incident, on December 9, 1971, indictments were returned by the Shelby County Grand Jury’s nine White and three African American members.

Three sheriff’s deputies – Lt. Theodore R. Wilks and Patrolmen Edward M. Bonham and Johnnie L. Roberts – and one city policeman – Michael J. Dougherty – were indicted on first degree murder charges. Four city policemen – Danny L. Davis, Larry R. Skelton, James B. Dyer, and William L. Graves – were charged with assault to murder in the beating of Calvin McKissack, Mr. Hayes’ 14-year-old companion in the truck. Police Inspector H. R. Ray was indicted on a charge of neglect of duty, a misdemeanor. All of the defendants were White except for Lt. Wilks.

Next: The Incident