In 1962, voters in all of Shelby County went to the polls and killed the proposal to consolidate city and county governments, so leaders turned their attention to find a different way to modernize City of Memphis government.

In 1962, voters in all of Shelby County went to the polls and killed the proposal to consolidate city and county governments, so leaders turned their attention to find a different way to modernize City of Memphis government.

Four years later, Memphians went to the polls and voted to change the structure of their city government.

Eight years later, Shelby County voters did the same, reinventing county government’s structure.

In both cases, voters eliminated the commission form of government in favor of a strong mayor form of government.

Before the change, in Memphis, there was the Mayor and Board of Commissioners. The mayor came from the five commissioners who managed the administration and operations of city government, but he had only marginally more power – largely through the bully pulpit – than his colleagues.

There was no City Council because the commissioners served both as the executive and legislative branches, and because they were elected in a citywide vote, there had never been African American members.

The momentum for a different form of government had been percolating for 25 years, and although some important reformers favored a Council-city manager structure, they were willing to support the mayor-Council structure to ensure change.

Change In The Air

In county government at the time, there were three commissioners in the administrative branch – one in charge of health services, one in charge of roads, bridges, and prisons, and one in charge of administration and finance. The legislative body was the Shelby County Quarterly Court whose chairman had over time assumed roles that would normally be considered administrative, blurring the lines of authority so that accountability was difficult and public confusion was widespread.

The Quarterly Court had become more representative as a result of a 1962 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Baker v. Carr, that required for the first time “one person, one vote” proportional representation. Until then, membership of the Quarterly Court overrepresented voters outside Memphis and underrepresented Memphians, particularly African Americans. It was a time when each of the towns was allotted its own seat on the legislative body although the representation of Black Memphians was tokenism.

In 1974, when voters went to the polls, they enthusiastically approved a government structure that largely mirrored the one that was six years old in City of Memphis. One of the prime motivations was for county government to be changed so it replicated the structure of city government in hopes of inspiring consolidation.

At the time of the vote on restructuring county government, consolidation had failed on its second referendum just two years earlier, and it was thought that changing the structure of county government would produce new urgency and interest in consolidation.

Voters failed to take the hint.

An Unexpected Blog Post

Despite the fact that the two large governments looked very much alike and faced each other across Main Street in downtown Memphis, there was not another consolidation vote for 36 years. And when it took place in 2010, it went down in flames outside Memphis and barely passed inside Memphis. The closeness of the tally inside Memphis surprised supporters although it had failed both inside Memphis and outside Memphis in an earlier vote.

I’ve written several times lately about consolidation and options for government modernization, but this specific post was not planned. Rather, it is the product of an incident of unexpected synchronicity.

In the midst of research in the Memphis Room at the Ben Hooks Central Library on a totally unrelated subject, a file pulled for me surprisingly contained information about the 1968 campaign to change the structure of City of Memphis government.

It provides historical context for a city government which is now being considered as part of a new metropolitan government. The arguments for changing City of Memphis government in 1968 are instructive because they were used six years later by the campaign to restructure county government.

For supporters of consolidation, the current 53-year-old structure of City of Memphis government has served its purpose and it is time for a bolder, more innovative governmental structure that can drive progress and growth. For others, that option is drastic when there are options for improving government using interlocal agreements and rationalizing government services.

The Program of Progress

This post is not intended to argue either way but merely to offer a look at an interesting chapter in the history of city government when the POP (Program of Progress) campaign produced a new, improved form of government.

There were pamphlets, newspaper ads, and radio announcements urging Memphians to vote for a different government. One radio announcement script said:

“I am very pleased to join with other civic-minded citizens in support of the non-partisan PROGRAM OF PROGRESS. The PROGRAM OF PROGRESS proposal to improve the structure of our city government represents the collective thinking of citizens from many walks of life. The recommended change in makeup of our city government is based on the advice and counsel of many from the academic world as well as government leaders in several communities.

“The recommended changes would bring our city government in conformity with the structure and practices of the leading, most progressive cities in our country. The principle of separating the Executive from the Legislative goes back to our founding fathers who wrote the Constitution. Every state government and every major city has very wisely and prudently separated the Executive from the Legislative branch of government. Experience has demonstrated that this demarcation in government functions has worked exceedingly well.

“A more streamlined form of government can help our city make even greater progress in the future. It is my hope that the people of Memphis will vote for these proposed changes which are motivated not by political consideration but by civic concern for the welfare of our fine city.”

POP Publicity

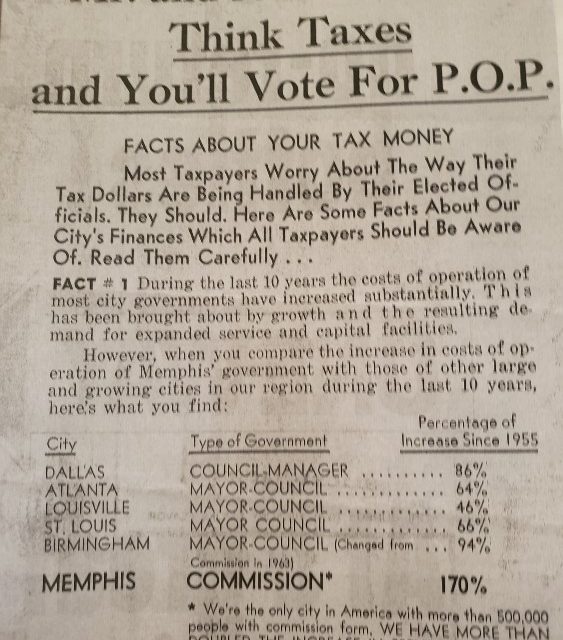

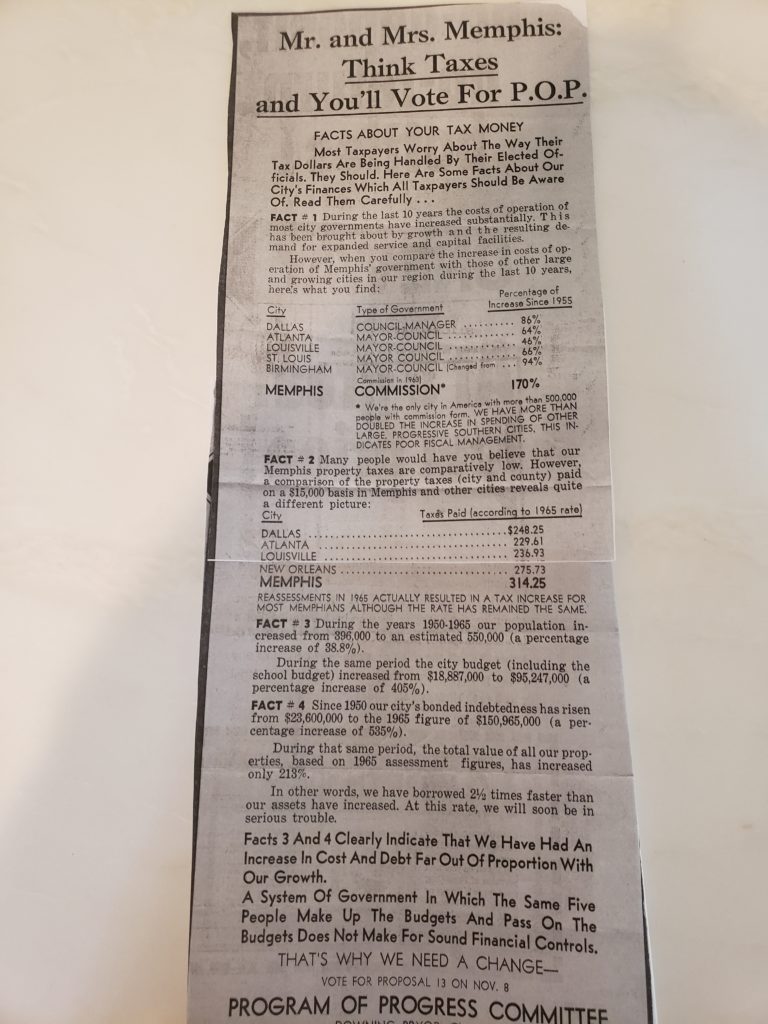

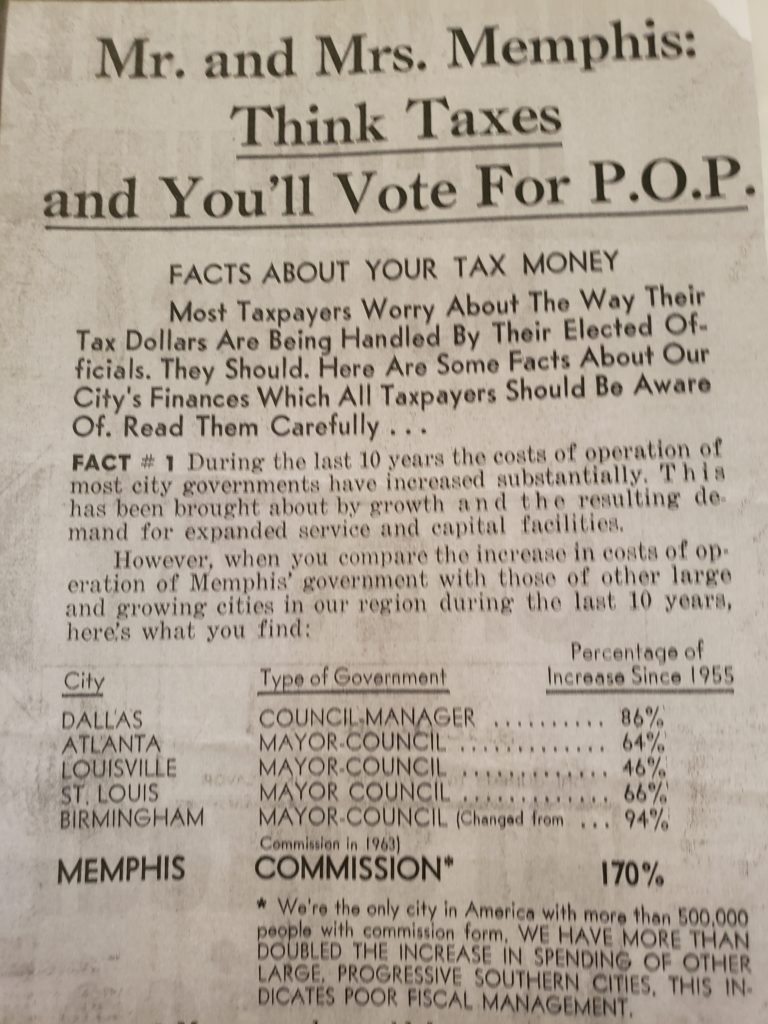

Meanwhile, newspaper ads said the cost of government and the amount of property taxes in Memphis were much higher than Dallas, Atlanta, Louisville, St. Louis, and Birmingham. It said the population of Memphis from 1950-1965 increased 38.3% while the city budget increased 405% and bonded indebtedness rose 535%.

“In other words, we have borrowed 2 ½ times faster than our assets have increased. At this rate, we will soon be in trouble,” the ad said. “A system of government in which the same five people make up the budgets and pass on the budgets does not make for sound financial controls.”

The directors for the Program of Progress Committee set their goals as 1) to study present government of the City of Memphis and other suitable forms of City government, 2) to hold public hearings, meetings, and discussions for proposed changes in the present charter, 3) to prepare the draft of a proposed new charter or amendments to the present charter, 4) to submit the same for public study, discussions, and approval by the members of the organization, 5) to undertake to educate registered voters in the city as to the desirability of change in government, 6) to inform the voters of the City of Memphis of the details and advantag0000es of the proposed new charter, and 7) to campaign for approval of the new charter at the polls in the elections called for such purpose.

The directors and their plan of action were put in place but membership to the program was opened to everyone. It implemented the meetings, the data gathering, the research, and debate that led to the public vote.

A New Chapter

As part of the campaign, the committee issued white papers, including one on the various forms of city governments in the U.S. Memphis was the last major city with a commission form of government.

Then-mayor William Ingram did his best to blow up the process because he decided that the movement to change government was aimed at him. The weak mayor-Council form of government had no persuasive advocates and although the Council-city manager form had some major advocates, the consensus ended up the recommendation to a strong mayor-Council form of government.

It not only promised more accountability, clearer lines of authority, and more checks and balances in the form of a City Council, but the first Council promised the potential of African American members. In the end, three of the 13 Council members were Black although just under 40% of the Memphis population was African American, beginning a history of underrepresentation that continued for decades.

Memphis voters approved the change at the polls 52,177-33,061, and it took effect January 1, 1968.

The new government was immediately challenged three months later when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in Memphis as a result of the recalcitrance and racism of its first “strong” mayor.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.