Thumbnail: Memphis launches a $1 million housing trust that is underwhelming when compared to other cities. It cries out for a robust program to increase home ownership and give all Memphians an opportunity to create wealth.

**

It’s a tale of two cities.

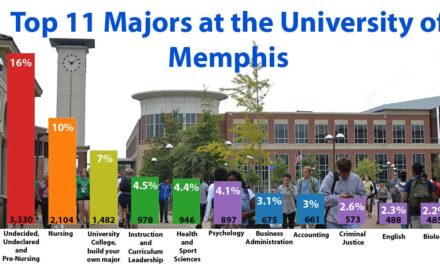

In Charlotte, 18 months ago, voters overwhelmingly approved $50 million in housing trust bonds and $55 million in neighborhood improvement bonds to execute its Framework for Building and Expanding Access to Opportunity through Housing Investments. It’s a detailed plan of action to expand the supply of high-quality rental housing and homeownership opportunities, improve existing rental housing stock, and support self-sufficiency as a result of the proximity of jobs with affordable housing.

In Memphis, about a year ago, the Memphis Affordable Housing Trust Fund was launched amid the fanfare of a major news announcement. Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland said it would be used “used to rehab and construct multi-family and single family housing in our city for people that just can’t afford it.”

City of Memphis funded this bold promise with $1 million.

Meanwhile, in Nashville, its housing trust fund receives $10 million from city government. St. Louis provides $5 million to its housing trust fund every year. In Louisville, its city-county government provides annual funding of $10 million.

Serious Challenges

In truth, there’s no correlation between the $1 million and the scope of the challenge in Memphis. After all, the city has an affordable housing deficit of 33,000 units. In addition, there are 30,000 vacant residential lots; 12,500 vacant houses; and 2,500 vacant apartment units.

It’s why Memphis 3.0 calls for housing of all kinds.

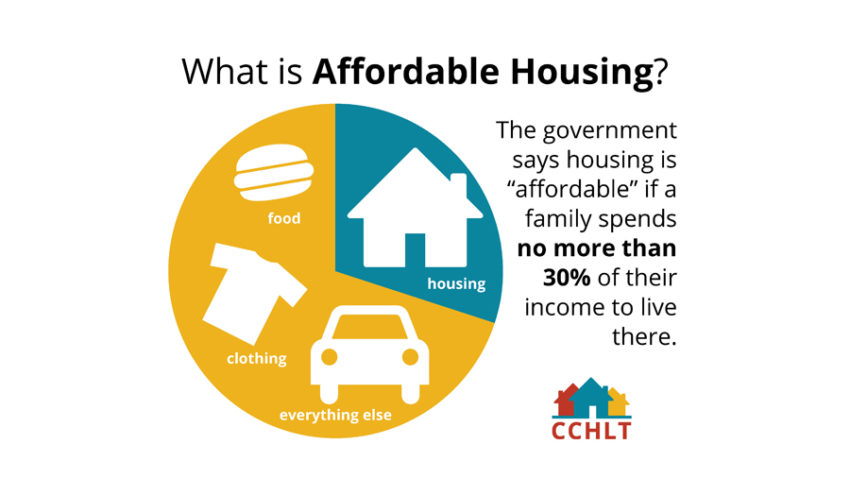

For context, consider that 43% of all employed Memphians make less than $15 an hour and to afford two-bedroom housing, an hourly wage of $17 is needed.

That said, it takes a wage of $15.19 an hour to afford two-bedroom housing in Frayser, North Memphis, Oakhaven, and South Memphis and $16.15 an hour in Whitehaven. And two-bedroom housing in the 38103 zip code is $25.58 an hour.

Already, in Charlotte, which has a long history of funding affordable housing, many are doubtful that the $50 million makes enough impact on the city’s housing needs. The affordable housing deficit in Charlotte is essentially the same as Memphis.

Charlotte Chamber of Commerce Leads

The final phase of Charlotte’s four-phased investment plan calls for an additional $170 million in bonds for neighborhood and housing improvements, bringing the total funding since 2014 to $759 million.

The campaign in Charlotte was led by its Chamber of Commerce although it would require a property tax increase, a position in stark contrast to the Greater Memphis Chamber of Commerce, whose default talking point is about high taxes in Memphis.

As the Charlotte Chamber seemingly understands, the tax rate is not about its how much it is, but how much value results from it. After all, some of the cities with the highest tax rates are the most economically successful.

When business leadership here can see beyond their tax bills and advocate for a reduction in the almost $1 billion in taxes that are given away in PILOTs every decade and for a plan of investment that creates more opportunity so more Memphians can engage in America’s primary source of wealth – homeownership.

Data Points

Here are some facts our business community doesn’t talk about but nonetheless underscores the need for an actionable, step-by-step plan to improve Memphis:

* Homeownership in Memphis declined from 66% to 59% from 2010 to 2017. No major city had a bigger drop in owner-occupied single-family housing.

* African American rental rates increased 26% from 2010 to 2017 while white rental rates only rose 3%. A major factor was the emergence of “vulture” firms who rushed into Memphis in the wake of the Recession to purchase as much as 20% of all homes on the markets in order to put new coats of paint on them and recruit renters to replace homeowners, and then inevitably evict them. In other words, renters lured into “lease to buy” houses not only lost their equity but they also got a bill for fees and court costs for the eviction lawsuit.

* Two-thirds of all Memphians in the central city – 652,1919 – live in strongly declining neighborhoods, which have lost nearly 33,000 people since 2000.

* About 27% of Memphians earn less than $20,000, which means housing costs take up a disproportionate share of income. Nationally, 88% of households with a median income of less than $20,000 are financially burdened to pay for housing.

* While City of Memphis only came up with $1 million for an affordable housing program, EDGE doled out more than $30 million in tax breaks for apartment developers. At the same time, a PILOT requirement that 20% of the units have to be affordable is largely window dressing when it comes to alleviating affordable housing.

Modern Red-Lining

Memphis MSA’s #1 economic opportunity is to close the racial income gap, which would in turn produce $22 billion in new GDP. On the rare occasion when the conversation turns to ending the income disparity, it focuses on workforce development, $15 as a living wage, any job is a good job, and other topics, but rarely talk about the connection between home ownership and wealth.

At the same time, the homeownership gap between whites and African Americans is now wider than it was during the Jim Crow era. A major factor is modern day redlining, which arguably isn’t as blatant as the racist government policies of the past but the results are the same, limiting opportunities for Blacks.

Despite banks’ boasts about supporting homeownership, the truth is an entirely different story as households that can afford an affordable house receive mostly lip service and no loan.

An analysis of 31 million government mortgage records showed that people of color were much more likely than whites to be denied a conventional home loan in 61 metro areas. Because of it, maps of mortgage approvals and home values in Black neighborhoods look the same as they did decades ago, and there is no reason to believe this is not the case for the Memphis metro.

Getting Serious About Investments

Here’s why this matters: economic inequality is the most significant challenge facing the Memphis region, and more and more research suggests that housing inequality may be the biggest contributor to the economic divide. That’s because without the wealth that comes from housing and land value, wealth is depressed for many people who traditionally have been African American.

And research indicates that the main catalyst for housing inequality is coming from the expanding gap within cities and metro areas, not between them. This economic segregation is exacerbated by factors like safety, schools, amenities, and access to jobs, and with no real, well-funded plan of action to increase home ownership and improve neighborhoods in Memphis, the racial income disparity is unlikely to change.

Meanwhile, other cities like Charlotte, St. Louis, Louisville, and Nashville will continue to make the investments that will have impact on housing, neighborhoods, and ultimately, economic health.

City of Memphis says it cannot afford to make this kind of major investment, but the question actually is, can it afford not to make it?

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.