Looking back, there’s no real argument that suburban sprawl was not a direct hit on the city at its center, draining Memphis of its people and its resources and crippling its fiscal health while new infrastructure in the suburbs demanded by developers was taking Shelby County Government to the brink of bankruptcy.

Along the way, our community bought developer propaganda that stated over and over that sprawl was growth rather than simply the biggest migration of people out of Memphis. Lost in the talking points was the fact that it was mostly taxes paid by Memphians that were paying for the infrastructure that was subsidizing the developers in the first place.

It was a cynical policy decision that ultimately required Memphians to invest in the deterioration of their own neighborhoods. That’s because the investments in sprawl required local government – primarily county government – to make a choice — between sprawl and urban neighborhoods.

Sprawl won. Neighborhoods lost.

Mayors Fought Against The Interstate

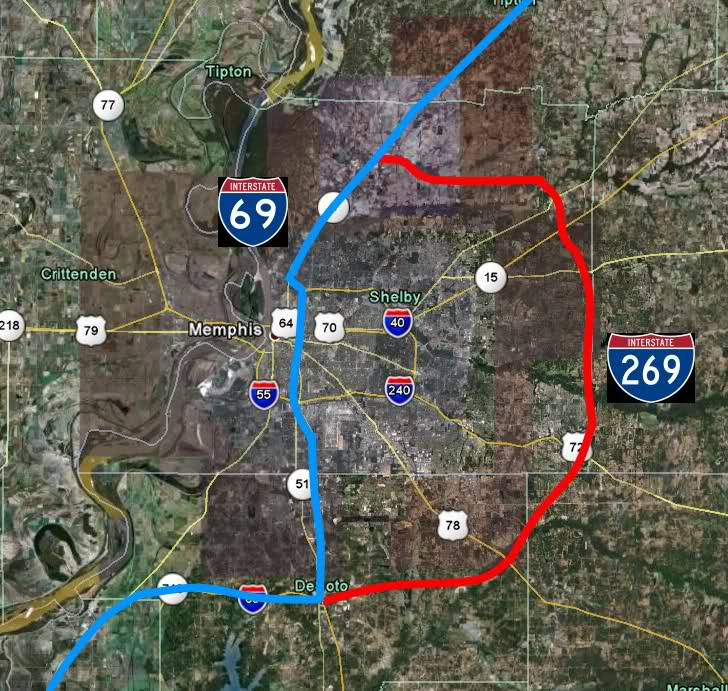

The mayors of Memphis and Shelby County – Willie W. Herenton and Jim Rout respectively -deserve credit in opposing I-269, citing its negative impact on Memphis but also questioning the need for the interstate loop hugging the eastern borders of the county. In the end, Mississippi politicians in Washington jammed it through the Congress and plowed over the mayors’ objectives in their haste to deliver the greenfields for their own developers, which in turn, gave the pork barrel project the green light to continue through Shelby County.

As a result, I-269 is a case study of how politics can obliterate smarter policy and how manipulation of public processes can benefit an influential and politically connected few. It’s also a case study of how difficult it is to mount a regionalism movement when suburban leaders seem oblivious to the importance of a strong city to their own future.

Because of this, forgive us if we don’t share the celebratory media coverage and the hyperbole from suburban politicians as the completion of I-269 draws near, forgetting that the Sierra Club once called I-269 one of the 50 worst highway projects in the U.S.

The construction of this unjustifiable interstate highway is one of the saddest chapters in the modern history of Memphis and Shelby County. Unfortunately, its negative impacts are just beginning.

Here’s our post from June 9, 2009, about how this interstate came to be:

Perhaps what local government needs most is a Department of Connecting the Dots.

While one public agency talks about creating a workforce that can compete in the knowledge economy, another gives tax freezes to companies that perpetuate low-wage, low-skill jobs.

While one government launches a “sustainability agenda,” no government seems able to rein in sprawl-inducing projects that make Memphis the most economically segregated of the top 50 metros.

While one department talks about keeping and attracting twenty-first century workers, another operates a public transit system that’s barely in the late-twentieth century.

While one division of city government works to revitalize urban neighborhoods, the projects of another make them more disconnected and less walkable and bikable.

The Symbol Of Unconnected Dots

If there’s a poster child for this disconnect, it is I-269. It’s essentially the latest gift to developers, but for Memphis, it’s the gift that keeps on giving, fueling trends that already batter the city’s ability to compete.

The Brookings Institution recently released a report that showed that jobs created within three miles of downtown are decreasing while those more than 10 miles from downtown are climbing. It underscored an earlier study by the think tank that showed that Memphis is a national leader in the loss of middle-income families and neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, the economic segregation caused by sprawl results in concentrated poverty that is the seedbed for our city’s most serious problems and derails our best efforts to address them. Projects like Tennessee Highway 385 and I-269 promise only to make them worse, because every problem becomes harder to deal with in cities that are economically segregated.

In other words, at the precise time when every city, county, and state agency should be focused on encouraging infill redevelopment that revives and stabilizes Memphis neighborhoods, our transportation investments hollow them out, and leaders appear unable to turn the tide and abandon the idea that sprawl is “growth.”

Hammering It Home

To their credit, both city and county governments opposed and lobbied hard to prevent I-269 from ever happening; however, in a high stakes game of political gamesmanship, Mississippi held all the cards, and former U.S. Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott owned the deck.

Lott was supported by former U.S. Representative from Texas and House Whip Tom (Hammer) Delay, who had earlier suggested that the I-69 Coalition hire someone who would be uniquely skilled in presenting its case in the nation’s capital. That person just happened to be his brother, who was paid about $300,000 a year. To DeLay’s hammer, Lott played the nail.

Memphis Mayor Willie W. Herenton and Shelby County Mayor Jim Rout were relieved when they thought their fierce opposition and relentless lobbying of the Tennessee Congressional delegation had blocked the interstate add-on that jerks eastward at Millington and runs along the far eastern border of Shelby County (dipping into Fayette County to open up those green fields to residential development and a rail yard) before swinging downward across unspoiled North Mississippi landscape. (I-69 itself reflected the premise that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line.)

Faced with defeat, Lott added wording to a federal bill that essentially took the decision out of Tennessee’s hands while stepping up construction of the interstate through his home state. In the end, it was like many road and highway projects in the region, born from a tradition of political patronage between government and developers that is embedded in our local DNA.

The Law Of Unintended Consequences

The project cost is now moving toward $1 billion, and backers now justify it with terms like smart growth, knowledge economy jobs, New Urbanism, and open space protection. They also claim that Memphis will benefit from new economic growth and development as a result of I-269.

At the same time, the cause and effect — connecting the dots — between sprawl, the climbing Memphis tax rate, and an economically polarized city are overwhelmed by the megaphones (political, civic, and media) enjoyed by those who drive such projects.

The inattention to the urban center that fuels our regional economy is symbolized by I-269, but its impact will be real and immediate. It will further produce an economically polarized city where fewer and fewer Memphis workers are paying more and more in taxes — including those spent for services and amenities that are in truth regional.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

I 269 helps people escape the city of Memphis

Good article. Unfortunately people don’t have a bigger understanding what urban and rural sprawl does.

This interstate will greatly benefit DeSoto County and northern Mississippi. It’s a way people can avoid having to drive through Memphis.

The suburban sprawl was going to continue whether or not this highway was built. Most middle class people will always prefer to live in a distant suburb that is safe and not in the crime of Memphis.

Sprawl is a rot that tends to consume the old city. We can hope that Memphis is just 20 years behind other cities, as people across the country have come to recognize that high-density living is actually easier living. Other old cities are coming back, maybe we will see the same for old Memphis in the next 10-15 years. If not, Collierville, Southaven, etc will ultimately find that the suburbs cannot be secure without the city.

David Ciscel issued early warnings about sprawl. In case you haven’t read it, here’s 2000’s The Cost Of Urban Sprawl in the Memphis MSA: https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/bridges/winter-2000/the-cost-of-urban-sprawl-in-the-memphis-msa

If Memphis is successful in refusing to extend sewers to the unincorporated county, then Fayette, Tipton, and especially Desoto will experience massive sprawl. They are already owned by greedy developers that have plagued Shelby County for so long. Much of Desoto is now experiencing the worst traffic problems in the metro area.

If only we could somehow see some of the growth and revitalization of our inner city neighborhoods like has been happening for several years in Nashville. Old houses in close in neighborhods are fetching $350-$450K and then torn down and replaced with a new house selling for up to $750!

Similar to I-269, middle TN has route I-840 which has been a huge help with traffic and to the economy in middle TN since it services ass the auto manufacturing in the area. Nashville and it’s surrounding areas are totally booming with a white hot economy and growth in the city, suburbs and surrounding towns.

Nashville has enough people moving into the city that it’s able to mask the problems that developed in the city as people moved in all directions but there are some trend lines that concern city officials. Officials in Nashville have lamented the construction of I-840 which, while making it have an Atlanta feel, also had sprawl’s too familiar negative effects.

And the population and economy are growing and strong in surrounding areas like Clarksville, Lebanon, Murfreesboro, Franklin.

This interstate is a great example of a backward-thinking concept and the city of Memphis will continue to struggle to grow because of it.

Apparently no one cares about the uplifting and economic development of Memphis – more reasons why there is crime and people move to suburbs.

Department of Connecting the Dots is much needed.

Only at “Smart” City Memphis would a major infrastructure project be viewed as a bad thing for the city. Thanks for my weekly chuckle. As dynamic cities like Dallas, Houston, STL, Nashville, Phiily, DC, SF, Salt Lake, etc, etc welcome such stimulators, we bitch about I-269 and if our delicate city can support a second concert venue. Quite sad, actually.

Howard, those cities expanded ONLY after the core cities were bursting at the seams. Since 269 is complete now except for the Lewisburg-Hernando stretch, there is not much we can do about this.

Here’s what we NEED to do first. 1) keep working on infill projects. 2) support the Mayor’s cutoff of sewer projects to the places outside the city limits, that doesn’t help the city at all. 3) work to get at least ONE, if not TWO more bridges over the Mississippi.

My suggestion is to extend westward from the 300 connector to Highway 51 North (yes, goodbye DeWitt Spain Airport), put a new I-40 bridge there and run it west directly into the current west 40/55 interchange at West Memphis. Next, once completed, tear down and build a newer, wider Memphis-Arkansas Bridge complete with a new interchange at Crump Boulevard.

As much as we don’t like 269, it is here, and we need Democrats in power to get Interstate 69 built from here to the Kentucky border, not just for us, but for all of West Tennessee as well.

Steve S., are you familiar with the MBJ’s “Crane Watch” or Cushman Wakefield – Commercial Advisor’s 901 RENews? Check it out, good info. I think there is something like 300+ development, redevelopment, infill, etc projects in some state of progress in the area, representing $12-13B in investments. Good news for all.

I will check those out, thanks.

I looked at the MBJ crane watch report. Then I looked at the same one for Nashville. We are a sleepy little town compared to the dozens of massive projects underway in Music City.

And the NBJ is reporting that Nashville will be awarded a major league soccer team tomorrow making 3 pro sports teams up there and a new stadium to boot.

Two things:

1) As we have said repeatedly, no city in the Southeastern U.S. can match Nashville’s growth, so it’s an unfair comparison. There are other cities that make more sense as peer cities.

2) I-269 is a done deal, but we need to exert the political will and obtain the knowledge and skills to stop any other anti-urban, pro-suburban gifts to developers that fuel sprawl, increase economic segregation, and stimulate more people to move out of Memphis.

Most of all, every road is not a good road, and we need once and for all to rid ourselves of that notion.

Anony, amazing what infrastructure development and an educated community will do for an area. I heard one time that the assets Memphis has, airport, rail, the mighty Miss, roads, are far, far superior to anything Nash has, but, the problem is, the difference is, Nash is a government town run by business while MEM is a business town run by gov. I think the I-269 expansion will fully benefit Memphis.

In the past 20 years, there have been a numerous gut punches to Memphis by suburban politicians, and this shows that these guys were not just in our own legislature but also Mississippi pols. It’s time to say, enough is enough. We will fight back. We can’t just lay back and look for someone on a white horse to rescue us. We have to rescue ourself.

Memphis seems to have been waiting for another Fred Smith to “save” the city. That’s never going to happen. It’s also arguable that putting our our eggs in the FedEx and distribution sector has not played out so well for the local economy since the majority of those jobs are lower wages. Memphis business and government leaders have been historically weak and their lack of foresight and complacency has driven this city to an all-time low.

I have to disagree about the Airport being a huge asset. It may be good for FedEx and cargo packages, but it is totally sub par for passengers with only 80 flights per day total. Our weak Airport hurts businesses large and small. Nashville’s Airport has 4X more flights and passengers. Most importantly Nashville is growing very fast and has a much better educated population with higher income levels. As always, Memphis is losing population and is far behind in its economy snd educated work force.

Memphis is more on par with cities like Birmingham AL, Jackson MS and Louisville KY. I think Little Rock is better off in most categories compared to Memphis.

I read somewhere once that Nashville has 2x the number of people in their msa that can afford an airline tic v Memphis, and, Little Rock, a much smaller city v MEM, has as many as MEM. Airlines are in business to make profits, and if there is not a market for their services, well…

All of the airlines carefully analyze each city they fly to. Any study of demographics shows that Memphis has a lot of poverty and a small corporate and tourism market. If there isn’t the demand there are few flights. This is why our airport sucks.

Bart:

For God’s sake please don’t mention guys on horses around here…

We’ve waited on guys on horses to save us for decades. That’s how we got Sidney Shlenker and John Tigrett and countless others. Then we look to other cities and try to copy what they do but that doesn’t work because it didn’t have Memphis same profile. Then we chase the latest magic answer or big project and 10 years later, we’re surprised that nothing’s changed.

We need to take responsibility for our own future with our own solutions and plans.

Highly doubt any more bridges across the Mississippi are in the cards.

I understand the need for the interstate between I-55 and I-22/us 78.When I-22 was first thought of 40 years ago, it was going to go from I-240 to Birmingham. There is no way that could be done today. So obviously you need a way to route traffic up I-22 into the heart of Memphis. I have no idea why that section isn’t I-22. As for I-269 from I-22 to I-40, it’s the most ridiculous and biggest waste of money on transportation in ages. I can’t think of one good reason to build that section.

You lost me when you quoted the Sierra Club. Whatever caused the issue of Memphis current state of depravation (which can be argued for days) the lack of a desire to HONESTLY and AGGRESSIVELY address the top of the nation crime problem has contributed more to said demise than all other positions combined. And I suspect the continuing downward spiral will continue…and the days of comparing Memphis and Nashville have long been gone…probably forever.

As an interstate truck driver, I can only see a benefit to the I-269 corridor being built. It will greatly relieve congestion on US 78 heading south towards Mississippi for trucks by linking I-269 to I-55. I can’t wait for it to open.

Smarty should try driving through Memphis every 5-10 years. All the way through.