Most people think of Memphis as beginning at the Mississippi River where the cobblestones are located and the first stirrings of a downtown taking place somewhere along Main Street between Jefferson Avenue and Beale Street.

It’s sort of like those romantic images of Andrew Jackson, John Overton, and James Winchester once standing on the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff and imagining a city so grand that it should be named for the legendary capital of ancient Egypt, located on another great river, the Nile.

Just as that never happened (the founders were never in Memphis at the same time and there’s an argument about whether Mr. Jackson was ever here at all), the conventional wisdom about Memphis early years is regularly wrong.

That’s why we’ve been excited that City of Memphis is going back to the future by concentrating on the city’s first commercial district – the Pinch – and extending the Riverwalk toward the first public landing – which fronted the Mississippi River at the Pinch District.

A Gut Feeling

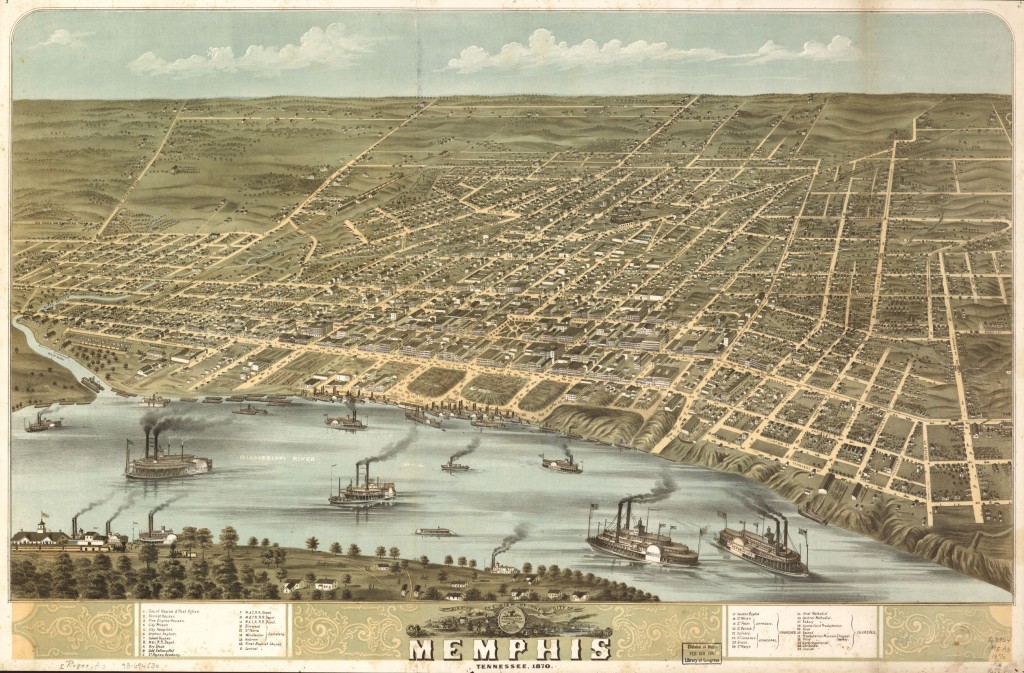

In the first decades after Memphis’ founding, businesses and homes in the Pinch District were located on streets that dead-ended at the Mississippi River. The isthmus that was the forerunner to Mud Island didn’t extend much beyond Jackson Avenue in the Pinch District where the mouth of the Wolf River was located, as seen on the 1870 map shown above.

It was the location of the First Landing in Memphis, notwithstanding the giant octopus on some maps that guarded the city’s front door.

The first store and post office in Memphis were opened by Marcus Winchester, the founder’s son, near today’s Jackson Avenue and Front Street in the Pinch District. He was the first mayor and a powerful man, but not powerful enough, according to some historians, for his career to withstand his marriage to a woman of color.

We all know the story about how the district got its original two word name from the “pinched gut” that characterized Irish immigrants but also because of the impoverished appearance of so many in the melting pot that was the Pinch neighborhood. In time pinched gun was shortened to Pinch, and if Memphis at that time reflected “grit and grind,” it certainly was in the Pinch District.

Hard Times

That grit and grind tagline applied even more to the area following construction of The Pyramid, a project that was supposed to revive the Pinch but instead sent it into a downward spiral as historic building after historic building was razed to make way for acres of Pyramid parking lots. The number of historic buildings declined from 43 to 19, and the area deteriorated to the point that in 2015, the Tennessee Historical Commission threatened to remove its National Register of Historic Places designation.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way, but city and county governments made a fatally flawed assumption: that the new arena would stimulate redevelopment of the historic area because the iconic building would be a 365-days a year attraction.

It was not to be. Proposed year-round use after proposed year-round use was advanced and fell flat – music theme park, Hard Rock Café, eco attraction, and cultural exhibitions – leaving the building to be activated about 30 times a year with basketball games and concerts. Even the inclinator to the apex of the building – long accepted as the only sure bet – didn’t even get built until Bass Pro Shops occupied the building more than 20 years after The Pyramid was built.

As a result, the vision of hordes of visitors to The Pyramid walking over to the Pinch and eating and shopping in its newly redeveloped businesses vaporized along with hopes of property owners looking for ways to monetize buildings that had stood empty for years. In the end, parking lots seemed the best – maybe only – bet.

In retrospect, it is easy to see a big part of the problem: there was no plan for revitalizing the Pinch District as part of the Pyramid development, no incentives established to help make it happen, and no meetings with property owners in hopes of creating shared strategies that would spark organic growth and attract investment into the neighborhood.

A Fog of Failed Opportunities

At the point that the Sidney Shlenker/John Tigrett partnership imploded and any dreams for their development at The Pyramid along with it, city and county officials were left with an arena that remained to be finished and contracts for concessions, souvenirs, etc., that collapsed with that partnership had to be put back together again in the matter of a few months in order for the University of Memphis to play its 1991-1992 season in the building.

It was accomplished, but just barely, and along with the city/county management of the building – subcontracted to Spectacor – the focus shifted to survival for the arena rather than accomplishing the dream of it as a year-round magnet for visitors to the area.

If that wasn’t bad enough for the Pinch, things only got worse. On opening night, the toilets overflowed and within weeks, it became clear that the sound in the building made the concert experience difficult at best – unless you enjoyed hearing every note twice. It led to a major redo of the sound system that took roughly two years when promoters largely scratched Memphis off its list of concert sites.

This also contributed to even more dashed hopes for spin-off economic benefits for the Pinch, and by the time the basketball schedule could be complemented again by a slate of concerts, a certain lethargy hung over the Pinch and not even the addition of the trolleys could lift it.

Begin at the Beginning

With the opening of Bass Pro Shops, hopes for the future of the Pinch were rekindled, and both the retailer and the district were counting on each other to maximize the overall economic impact. The bridges that served the Pyramid when it was an arena did not serve it as a retail store, essentially because the bridges were a dead-end because of the hotel added to the building, and the Wharton Administration delayed construction of a new bridge until the plans for the Pinch District were fleshed out.

Enter the Strickland Administration, which moved ahead with more resolve on the planning process for the Pinch that had been begun haltingly in the waning days of the Wharton Administration. This year’s final planning report’s four goals were to build on the history and texture of the Pinch District’s sense of place, to create mixed use place, to encourage a walkable neighborhood, and reinforce connections to adjacent institutions and neighborhoods, notably The Pyramid on the west and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital on the east.

These values were baked into the Strickland Administrations vision for the Pinch area as part of what the city calls the “game-changing” Bicentennial Gateway Project, the most imaginative plan unveiled in Memphis in decades. City officials presented the concepts for the plan at an open house at the Memphis Cook Convention Center on Feb. 16, and while there are many components to the vision, chief among them are the rebirth of the Pinch District and the extension of the Riverwalk connecting to the First Public Landing in Memphis.

Like many people who love Memphis history, we have hated the condition of the Pinch District and the lack of respect that the city’s first commercial area received. The area is so central to the development of Memphis itself but more, it was central to the development of the Memphis personality and character.

Four Public Landings

That’s why Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland’s vision for the Pinch area is so exciting. We understand that there will not be lots of cranes in the sky over the neighborhood anytime soon, but we do know that the mayor’s ideas for the district could provoke the kind of organic growth that has been needed since the construction of The Pyramid and decades before.

Meanwhile, we also appreciate the attention to extending the Riverwalk to the area of the First Public Landing in the Pinch in 1819 between Auction and Winchester Avenues. In Memphis history, there were four public landings: the South Memphis Landing between Union Avenue and Beale Street circa 1838; the Center Landing between Poplar Avenue and roughly Adams/Washington in 1844, and the “Cobblestone Landing” (aka Great Memphis Landing) between Jefferson and Union Avenue in 1850.

The Pinch District developed as the city’s first commercial district largely because of its close location to the public landing provided for in the 1819 plan for Memphis. The importance of the landing began to wane by the 1830s with the growth of a sandbar across its frontages. There was a wooden walkway and wharf were built across the bar in 1837 at the end of Winchester Street, but the sandbar’s continued growth rendered the wharf useless by 1838.

By 1841, Memphis did not extend much beyond Poplar Avenue, and in fact, there was only one brick house south of Poplar, and much of the city were open fields and woods known as great places for the hunting of squirrels and game.

Back to the Future

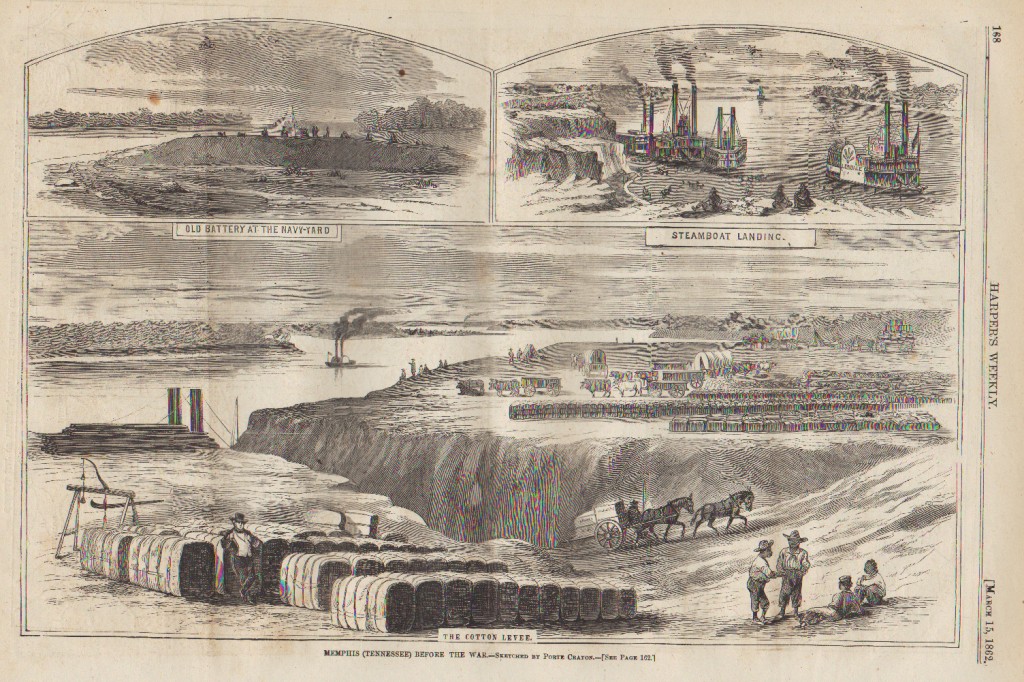

Although city officials tried to discourage flatboatmen, who dominated river trade and often defied local authorities’ control them, from using any locations except the first public landing, they may have won the battle – the “Flatboatmen’s War” – but they lost the war as Center Landing developed as the focus for river travel prior to the Civil War.

If there is any doubt that Memphis is indeed a river city, it is removed by the fact that several of these public landings were operating at the same time. Back then, the riverfront front was largely a broad, smooth, steeply sloping embankment in front of a steep bluff edge.

We digress, but we are excited by the plans for Memphis’ future to emphasize its rich past. While we have written often about the need for a more vibrant core downtown, we would hate for Memphis’ first downtown to be allowed to become a mere footnote in history.

****

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.

This has interesting historical information but the downtown of today is still a total mess. The south riverfront needs more help than does the pinch district. With the interstate, bridge ramps, the cut off tacky Bass Pro Shop and St Jude campus much farther east, there is just no way this entire area will ever develop to be a vibrant part of downtown. It abuts the bland barren government buildings area and those empty firetraps known as 100 North Main and Sterick Bldgs which will never been anything and need to be demolished in the interest of public safety. We need to focus scarce resources more into the core nearer Union and finally do something about the bigger and more majestic riverfront south of this area. More pipe dreams and decades of civic planning about what downtown needs have produced very little tangible improvements. Expect very little. So typical of this city.

First just fix the areas around Beale St Landing and Tom Lee park. The

boat landing seems to be floundering with restaurant and the One Beale development has never materialized. Need to concentrate on one area and do it right. Either do Pinch or the cobblestone park landing. Can’t afford both. Just my 2 cents.

It’s not either – or. And it is possible to afford both if Pinch District is funded with TDZ revenues, not city property taxes. Agree about floundering restaurant – not to mention godawful souvenirs at BSL.

I think the moral of the story is grand rebuilding projects initiated by government almost never work out. There is too much risk embedded in a single structure. I think incremental development in the Pinch District would be the preferred approach. Have the form-based code in place then subdivide the parcels in the way that they used to plat land for the 19th century downtowns. Then let St Jude in conjunction with many small-scale developers build mixed-use structures. The city could help coordinate construction of a collective parking structure or 2. Risk is then spread over a number of developers rather than putting all your eggs in one massive development basket.

I do not see the Pinch District having the potential to be a vibrant, well connected part of downtown. It is very isolated at the north edge and barricaded by the highways. St Jude’s building program will never reach far enough west and incremental mixed-use development of all those empty lots would take decades with huge risks for investors.

The market will tell. We’ll know based on the reaction of developers. But the millions of people shopping next door are a big hook.

These two are close to Pinch area but I’m asking why can’t the city do something to force the owners of the Sterick and 100 North Main buildings to either rehab them or tear them down? There should be deadlines imposed for the sake of public safety. One or both are going to catch fire again. These are huge issues for urban blight when two if downtown’s tallest buildings are empty snd literally falling apart.

The Pinch district area is also very walled off from the Bass Pro Shop. It will take many many years for this area to develop.

The pedestrian bridge being designed now and connecting Bass Pro and the MATA trolley stop to the blocks targeted for redevelopment will increase and strengthen access. It will take many years for the area to develop organically, but there’s no time like the present to give it a spark.

Tom Jones,Smart City

What do you think can be done about those 2 empty skyscraper buildings mentioned (100 N Main and Sterick)? I think it’s very very unlikely either can be rehabilitated. Both are eyesores and totally empty and falling apart. It would likely be cheaper to demolish. What do you think will need to be done