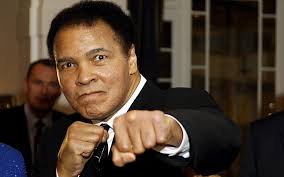

Muhammad Ali always said he was the greatest, and as far as I was concerned, he was.

He was one of my earliest heroes – brash, larger-than-life, courageous.

He exemplified a new generation, he gave voice to those of us who opposed the war in Vietnam and he inspired us to take action. After all, if he was willing to give up everything he loved for his beliefs, surely we could take a stand.

He was an icon before we knew what icons were. He was fearless, changing religions, names, and directions. He was a lesson in resiliency, refusing to be broken for his political positions. As a result, his biggest battles were outside the ring, where he took boxing to an art form.

Fighting outside the ring against forces trying to force him into conformity and shape him to their political points of view, he enflamed his opposition even more by changing his name from Cassius Clay and becoming a member of the Nation of Islam when he was only about 22 years old, later becoming a Sunni Muslim.

Getting Up When Knocked Down

As recently as six months ago, he said: “I am a Muslim and there is nothing Islamic about killing innocent people in Paris, San Bernardino, or anywhere else in the world. True Muslims know that the ruthless violence of so called Islamic Jihadists goes against the very tenets of our religion…Speaking as someone who has never been accused of political correctness, I believe that our political leaders should use their position to bring understanding about the religion of Islam and clarify that these misguided murderers have perverted people’s views on what Islam really is.”

For those who had watched his life, the comments were unsurprising. He’s been speaking out for 50 years. Back then, in a then-homogenized America, he became a pariah to so many, attacked and persecuted relentlessly by politicians and the media.

The forces arrayed against him set out to teach him a lesson and put him in his place. But it was not to be. Shunned by his friends and marginalized in his sport, his greatest battles were to be fought outside the ring and his steadfastness to his values and his faith were in the end his crowning legacy as he weathered the attacks and refused to back down.

He also taught the lesson of getting up when knocked down. He was convicted of draft evasion and sentenced to five years in prison, but the conviction was ultimately unanimously overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Ali’s Memphis Chapter

By then, he had become a role model for much of his generation, and when he returned to boxing after four years of exile, there was a new spirit of support even as he went down to defeat, setting up the unforgettable “The Rumble in the Jungle.”

His exit from boxing deserved better. He did not quit at the top, and slowly, it was clear that he should retire. That said, he did it on his own schedule, and that was to be expected.

He won very possible accolade for his boxing prowess, but here, he is best remembered as a role model for racial pride, social activism, and his refusal to go along to get along.

He had a Memphis chapter to his story with the Muhammad Ali Town II Cinema at Beale Street and Fourth, which was spearheaded by Memphians George Miller and Calvin Taylor. An added bonus for them was the time they spent with Ali in the Caribbean for several weeks while hammering out the deal as he trained. Ali came to Memphis in 1976 for the grand opening, where he engaged Rep. Harold Ford Sr., and City Councilman Mike Code in a faux boxing match and enjoyed himself so much that he said he just might retire to the city.

Not Me, Champ

In 2002, I was attending a conference in Louisville, which was also attended by Carol Coletta. After a brief tour of downtown, we returned to the historic Brown Hotel, where the meetings were being held. We were chatting when the door of the elevator opened, and we were barely paying attention as we started stepping on.

It was then that we noticed that the two people in the elevator were Muhammad Ali and his wife.

We didn’t acknowledge him, assuming that he was tired of strangers always intruding into his life. And yet, as the elevator began moving, he turned his head toward us and smiled impishly. We smiled back, but didn’t speak, still assuming that it was more polite to remain silent.

At that point, he slowly raised his fists in front of his body, smiling and motioning for me to put up mine. By then, we were all grinning, and I said: “Not me, champ.” He laughed, the door opened, and they got off on his floor.

Later that evening, he was a guest of honor at the conference, which was being held in his hometown. By then, he had been struggling with Parkinson’s for 18 years, and as a result, his body movement were slow, his speech was slurred, and he had developed tremors. And yet, the same charisma was present, and it seemed to me that there was an aura around him.

Knowing that he could not stay for the entire evening’s meeting, I walked to the head table and asked him to autograph my copy of his biography. Displaying the good humor for which he was known, he didn’t just sign the book; he signed it five times on various photographs on various pages.

On the photos that were taken before he changed his name, he signed Cassius Clay. On the later photos, he signed Muhammad Ali. Clearly, the change in his name was the dividing line in his life as much as it had been in ours.

Ali would be sad and dismayed at the violence and death that brothers are committing in cities all over the country. The downtown Memphis shootings this weekend and death of a police office are horrible and a stain on our city. It’s happening far too often especially here in Memphis.

RIP Ali. May your legacy be peace.

“If the measure of greatness is to gladden the heart of every human being on the face of the earth, then he truly was the greatest. In every way he was the bravest, the kindest and the most excellent of men.” -Bob Dylan on Muhammad Ali