Memphis and Shelby County leaders have received yet another wake-up call, and after more than 20 years emulating Rip Van Winkle, the question now is whether anyone will finally step up to address the fact that Memphis is a shrinking city.

That is not to say that taking such a stance is free of risk.

After all, a mayor in Detroit lost his office largely on the pushback to saying his city should be smaller; however, is that risk greater in allowing Memphis to continue to drift into the future with no specific action plan for a declining number of people on its 295 square miles?

The latest wake-up call?

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Shelby County was #1 in the entire U.S. in the most population loss between July, 2023, and July, 2024 for counties with more than 20,000 people. The county lost 3,379 people, and analyzing data from U.S. Census Bureau, it’s unquestionable that the loss was inside Memphis. The overall population of the smaller municipalities is stable.

Memphis Has Already Shrunk

A few years ago, 60 Minutes broadcast a post mortem on the death of Detroit. Its conclusions: Detroit had simply gotten too big to deliver public services efficiently or affordably.

Is it possible that the same diagnosis applies to Memphis, which today is delivering public services over an area two times larger than Detroit?

It’s conceivable that pushback in Memphis on reducing its size would not be as severe as it was in Detroit. After all, Memphis has already reduced the size of the city. In 2021, the city carved South Cordova, Southwind-Windyke, Eads, and Rocky Point and its about 11,000 people out of Memphis.

Then too, looking back, there are now widespread questions about whether Memphis aggressive annexation policy for 35 years was wise public policy. After all, several dozen annexations increased the city’s land area 60% while the population grew by 6%, peaking with a population of 650,100 in 2000 before declining almost immediately.

In other words, Memphis was raising revenues for public services from essentially the same number of people but now the service area was dramatically larger. The math just doesn’t work.

After 1970, when City of Memphis decided to use aggressive annexation to chase Memphis taxpayers moving out of the city’s 1970 border, city government failed to treat it as the choice that it was – a choice of shifting money to pay for services in the new sprawling areas or focusing on inner city neighborhoods that were declining for lack of investment.

In the end, sprawl won, and in effect, taxpayers in the inner city ended up paying for their neighborhoods own decline as their tax dollars were needed for new infrastructure and to expand services in the newly annexed areas.

What is the Right Size?

Memphis dodged a bullet in 1997 but the Tennessee Legislature had effectively put a target on its back. In 1997, the Tennessee Legislature passed the “tiny town law” of 1997 that would have allowed the incorporation of new cities in Shelby County – and a dozen proposals quickly sprang up.

Although it was ultimately declared unconstitutional by the Tennessee Supreme Court, the Legislature wasn’t done. In 2015, it changed the rules of annexation in a law that effectively meant that Memphis would never annex again. No longer could cities unilaterally annex areas. Instead, the areas could only be annexed with the approval of the people who lived there.

Memphis’ history of aggressive annexation was over. And yet, the Legislature continued to target Memphis with consideration of a law that would have forcibly removed some of the latest and loudest annexation areas. City of Memphis announced that it would launch a “measured approach to rightsizing process” for the city.

But that’s not what it really was. It was a political, not a planning, exercise. It was actually about doing just enough to get the state legislature off Memphis’ back. The ultimate question about Memphis’ right size was left unanswered.

That doesn’t mean that it’s still not a question that deserves an answer. Are 295 square miles too much for City of Memphis to manage and deliver services? Does a different size make more sense in terms of efficiency, tax fairness, and in Memphis 3.0’s emphasis on density as a driver for a better Memphis (density today is half of what it was in 1960)?

Density Cut In Half and Now Driver for Memphis 3.0

These are not easy questions with easy answers, but yet, they are worth asking. Perhaps the answer would be that the right size for Memphis is exactly the same size it is today, but maybe, just maybe, a smaller or more compact size makes more sense.

It’s worth remembering that the population of Memphis was 650,200 people in 2000 and today that has declined by 31,461 to today’s level of 618,639. Projections are that the population will continue to decline.

Memphis masked the beginnings of this loss by propping up the population with annexation after annexation, but that bubble burst when the Legislature changed the rules of the game. In other words, annexation meant the total number of people in Memphis stayed relatively the same over five decades despite 170,000 people moving out of the 1970 city limits of Memphis.

While Memphis is making a big bet on increased density in Memphis 3.0, adding more and more land over several decades dramatically reduced density in Memphis. In 1960, the density was 3,857 people per square mile. Today, it is 2,085 people.

On the surface, the reduction in density complicates the recommendations of Memphis 3.0, but again, does it or not? Answering the question of the right size of Memphis would tell us. It is especially timely considering tight city budgets and how public services cost more for low density neighborhoods.

Needed: Candor

Even if that study does not take place, it does not obviate the need for a leader to take a risk and pursue answers about the city’s loss of population and what plan could be developed to address it.

It would first require Memphians to decide what they want – do they want a plan giving incentives for college graduates to remain here and incentives for more people to move to Memphis or do they want a plan that focuses on improving existing neighborhoods and quality of life or do they want to set a priority list for investments aimed at long-term growth?

If Memphis is to increase its density, it’s already obvious that neighborhoods do not want more existing homes converted to duplexes or fourplexes, more multi-family housing, or more absentee ownership. Perhaps, the best scenario of all for increasing density as laid out in Memphis 3.0 is to lure back some of the 170,000 people who moved out of the city and into the ‘burbs.

At this point, we have many more questions than answers, but that’s because there’s been no real process to find the answers – provocative, data-based, and action-oriented answers.

Most of all, it requires leaders willing to be honest about the depth of the challenge confronting Memphis.

After a recent commentary by me about Memphis’ population loss, a member of the Greater Memphis Chamber’s Chairman’s Circle asserted that I was wrong because Memphis was growing. He spoke adamantly about it because that’s what he’d been told. He was likely confusing MSA population with Memphis population because the Chamber often refers to Memphis bragging rights by using MSA data. _

The U.S. Census Bureau numbers couldn’t be more graphic. For 25 years, Memphis has been losing population. We should not give in to cheerleading that says otherwise because it distracts us from taking action.

If Detroit Can Do It…

Meanwhile, as for Detroit, its transformation from gloom and doom to boom proves one thing: the power of risk-taking leadership that addresses a city’s toughest problems.

Only a few decades ago, the city was the poster boy for urban decay and failure. It had lost more than half of its population. Its poverty rate remained intractable. It entered bankruptcy a dozen years ago. Its downtown was mostly a ghost town. Neighborhood blight was rampant. City services were failing.

The city seemed finished. There were few life signs and few reasons for optimism.

And yet, today, it has defied all expectations. Population is growing for the first time since the 1957. Housing values are rising. Murder rates are the lowest since 1969. Government services have been reformed and no longer are people waiting an hour for a response from police.

All in all, Detroit is a city that refused to die. And much of it has to do with the election of Mayor Mike Duggan in 2014. He resigned as president and CEO of the Detroit Medical Center to run for office. After failing to qualify, he mounted a write-in campaign and won the primary with 52% of the vote and later the general election with 55%. He never looked back, receiving more than 70% of the votes in subsequent elections.

He did not sugarcoat Detroit’s problems. He put them out front and mobilized others to join him in the fight for their city’s life.

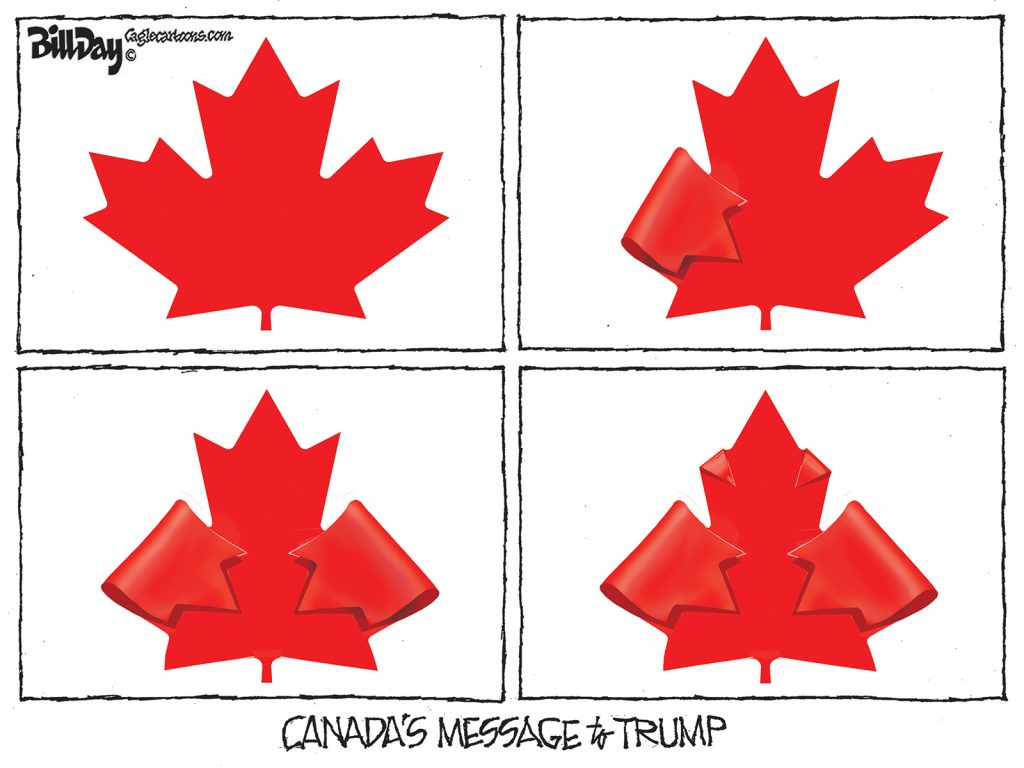

Memphis shouldn’t allow itself to reach similarly dire conditions. Like Detroit, it requires candor in presenting the structural challenges before it and embark on a long-term plan that can turn things around.

**

These commentaries are also posted on the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram along with occasional articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.