There is no argument any longer that sprawl has been the bane of existence for Shelby County.

Motivated initially by politics, it brought county government to the brink of bankruptcy, decimated Memphis urban neighborhoods, intensified poverty, and institutionalized economic segregation as a fact of life.

No longer is anyone willing to parrot the argument made back then by the Chamber of Commerce, politicians depending on suburban votes, and real estate developers with their disproportionate influence who contended that sprawl was “economic growth.”

Decisions were actually rooted in the belief that county government’s financial support of sprawl would keep White voters inside Shelby County where Republican candidates could still have a chance at the polls (a decision which delayed the Democratic Party takeover of Shelby County Government for at last 10 years but whose inevitability should have been obvious to anyone who could read a demographic trends map) instead of moving outward but also building more homes and roads would pump vitality into the local economy.

Even City of Memphis bought into it, extending sewers freely on the pretense that it would ultimately have the right to annex the areas, propping up its population numbers and its revenues as it chased its former taxpayers who in turn chased lower taxes and newer public infrastructure.

It was a classic failure of planning because it was based on the belief that nothing would ever change. Until it did.

Step 1: Incorporation; Step 2: Annex

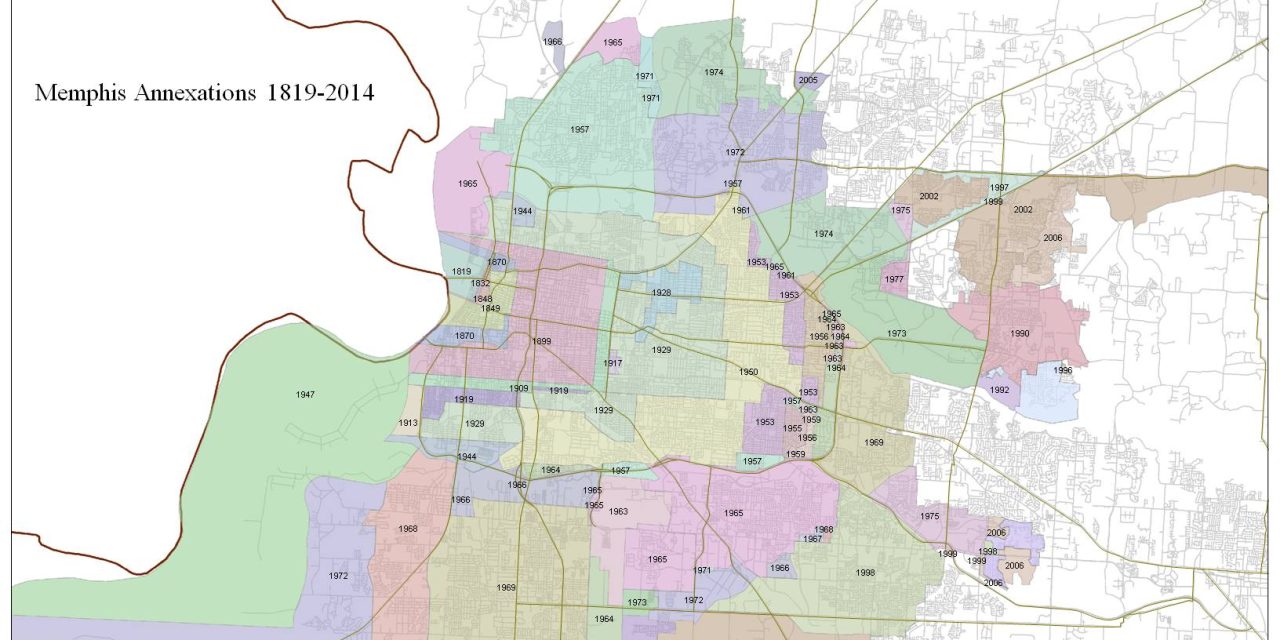

From the beginning Memphis recognized the power of annexation.

The city was only 13 years old when it approved its first annexation in 1832 when it had fewer than 2,000 people living in it. By 1999, it had annexed more land 77 times, including the towns of Manila, Madison Heights, Idlewild, Lenox, and Binghamton, swelling the size of the city to 355.46631 square miles and reducing its density by half, driving up the costs of public services inside Memphis and requiring taxpayers in the urban core to pay for the decline of their own neighborhoods as their tax money was spent on spawl rather than reinvesting in areas hollowed out. Densities of once healthy Memphis urban neighborhoods were cut in half as empty lots where houses once stood were more and more commonplace.

After decades of extending sewers beyond the city limits and annexing the developed area into Memphis, the Tennessee Legislature in 2014 flipped the script. It changed state annexation laws to take the power away from city governments and put it in the hands of the people targeted for annexation. It also blew up the annexation agreements between Memphis, Millington, Bartlett, Arlington, Germantown, and Collierville that set out which city could annex what.

The change in the law, which required annexation by referendum in the future, not only eliminated annexations as they had been known in Tennessee for a century, but led Memphis to do something thought unimaginable only a few years before – it deannexed parts of the city. Gone were Eads/River Bottom, Southwind/Windyke, South Cordova, and Rocky Point and the roughly 11,000 people living there.

City Hall called it “rightsizing Memphis” although it didn’t actually address what the right size really should be but dealt with the political troublesome areas of Memphis who had made the most noise about getting out of city. In that way, it was political sloganeering posing as a thorough analysis, an analysis which could have actually been useful in plotting the best future for Memphis.

All In

By the end of annexations as we knew them, Memphis’ land area was bigger than Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Atlanta – combined. And in the process, more than 170,000 Memphians had moved out of 1970 Memphis into the green pastures incentivized by county funding.

Looking back, it is interesting how Memphis was all in on annexations. The Memphis and Shelby County Planning Commission in 1967 wrote a report, Annexation: A Must for a Growing Memphis, that even urged more aggressive actions to annex areas like Whitehaven and Raleigh. It also predicted that by 1990, the county population would be 1.3 million, which is 44% more than it is today, 35 years later.

But the planners were not alone. Former Albuquerque mayor and author of the influential 1993 book, Cities without Suburbs, was telling Memphis leaders that “the ability to annex land from its surrounding county is a primary determinant of its fiscal health” with his underlying message of “keep up the good work.” In subsequent years, it seems that he was talking more about the need for resilience and the potential of regionalism, but Memphis had cast its lot firmly with annexation.

In an October 25, 2023, Smart City Memphis blog post, Memphis Flexes Its Sewer Power, John Branston quotes the Golden Rule as stated by developer Cary Whitehead Jr.: “He who controls the sanitary sewer rules the world.”

Memphis Is Shrinking

By the time Memphis wisely shut down its beneficent sewer policy, it had managed to disguise population loss from 1970 with aggressive annexations which misled many urbanists into thinking the city’s population remained stable. With the loss of the ability to annex and with Memphis nakedly exposed, it’s more than evident that it is a shrinking city.

1980 – 646,174

1990 – 610,337

2000 – 650,100

2010 – 646,889

2020 – 633,104

2023 – 618,639

And just as no one stepped forward decades ago to consider a scenario of a time without annexation, the city awaits someone to step forward to consider strategies for a city that is losing population.

But back to the subject of sprawl, the “great migration” in Shelby County began around 1970 in the wake of the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., school busing, the abandonment of downtown, the deflated civic spirit, negative national media coverage, and mounting economic woes. White people voted with their feet and it led thousands of them to move outside of Memphis, but that wasn’t all: the era of White flight was followed by Middle Class Flight which saw Memphis at the top of the rankings for cities dealing with middle class loss.

A telling data point: in 2000, 11.4% of the population of DeSoto County was African American, but by 2023, it was 35.2%. The sprawling out-migration was now color blind as both Black and White middle income families left Memphis and Shelby County.

The result of this historic movement of people in the Memphis region has been multi-dimensional but the issues that were challenges in 1970 became more intense and entrenched as a result of decades of sprawl.

The Price of Economic Segregation

Most of all, in study after study, Memphis was among the cities with the most economic segregation…and sprawl exacerbated the issue because of disinvestment in urban neighborhoods, blocked the inability to bring promising programs for our children to scale, and the lack of political will to drive a stake in the ground with a specific vision and plan to increase Black wealth, the single most significant economic development opportunity in our region.

That’s why More for Memphis is more than just a promising comprehensive plan to improve opportunities for economic mobility. It’s also a test for whether political leadership has matured to the point that they hear the priorities from the grassroots and can craft a way that allows local government to participate hand-in-hand with nonprofits and neighborhoods. In addition to political leadership, it requires the nonprofit organization which has overseen and managed this process to do something that is often the hardest: share power with grassroot leaders and give them the power to control their own destiny.

So many of the problems outlined in the More for Memphis plan were deepened because our community took its eye off the ball as it spent billions on sprawl. As a result, economic segregation metastasized limited access to jobs, long commutes and the need for everyone to own a car, increased costs of public services, reduced earning potential, and trapping families in cycles of poverty.

The impact of lost income from growing up in a sprawling neighborhood rather than a compact one is $3,000 a year, according to new research by the University of Utah. Co-author Kelsey Carlston wrote: “If someone grew up at a tract in a 10th percentile spawl, so very low sprawl, rather than a 90th percentile sprawl, which is very high sprawl, their expected annual income was $2,864 higher, which was almost 10% or a few percentage points in the income ranking.”

Put another way, while children from low-income families see reduced earning potential in sprawling areas, the opposite appears true for wealthy families.

Robbing Low-Income Children of Their Future

It’s an especially bleak fact of life for Memphis low-income children.

Tomeka Hart Wigginton summed it up in a column in MLK50: “A whopping 36% of Memphis’ Black children suffer poverty; only 10% of her white children do. To that end, analyzing Opportunity Insights’ research and tools, Mandy Spears of the Sycamore Institute found that “a child who grew up in a low-income home in Midtown had about a 16% chance of becoming a high-income adult. One mile away in North Memphis, a low-income child had less than a 1% chance.”

When the New York Times charted this same factor a few years ago, it concluded that poor children in Memphis had the worst odds of any place in the continental United States – at only 3%.

Looking in the rearview mirror, it’s easy now to see the price Memphians ultimately paid for doubling the land area. But for me, the main lesson of these years is that Memphis and Shelby County moved blindly to annex more and more without pausing long enough to consider what the ramifications might be for inner city neighborhoods and to consider that unlimited annexation might not always be the law of the land. More than anything, we adopted the talking points of the special interests to the point that we could not fathom that we could be wrong.

Hoping that things will be better is not a business plan. A real plan requires scenario thinking that explores all options and brings the community together behind a shared understanding and commitment to a mutual future.

**

Join me at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram where these blog posts are published and the conversation continues.