Note: I am proud to once again write the City Journal column for Memphis magazine. The following is the column from the December, 2024, issue. You can subscribe to Memphis magazine here. Tom Jones

Here’s the column:

A discussion on social media about population loss prompted former Memphian Chris Clifton to sum up the city’s challenge: “It’s all about having critical conversations about outcomes and the leadership to take us to our new Memphis.”

Clifton, former executive vice-president and chief operating officer of the Greater Memphis Chamber and now head of economic development in a South Dakota city, cut through the angst about the city’s loss of people to get to the essence of the question that remains to be answered: what exactly is the plan for Memphis to address its declining population?

The data prompting the question are unquestionably brutal. They led former Mayor Jim Strickland in 2020 to call population loss Memphis’s #1 challenge; however, his administration’s response was to challenge the U.S. Census Bureau’s tally rather than mount a process to understand and address the forces and factors producing the loss.

City Hall alarm bells sounded because the Census Bureau reported that Memphis had lost 13,785 people in the 10 years between 2010-2020. Despite that burst of concern, little has been said when the Census Bureau more recently reported an even more sobering fact: that between 2020-2023, the trend accelerated with the loss of an additional 16,786, which meant that Memphis has lost 28,250 people since 2010.

Memphis often lags national trend lines and there are those who hope that this is another case where Memphis will eventually play catch up. And yet, hope is not a business plan.

Such a plan should get the special attention of local government. After all, fewer people translates into fewer taxpayers, fewer people buying homes and paying property taxes, and fewer purchases by people paying sales taxes. To top it off, for many programs, it means reduced money from programs in which the federal government bases funding to local governments on their population.

Although population loss was common in almost all large cities during the pandemic, most are bouncing back; however, Memphis’s challenge runs much deeper and began long before the pandemic. What’s gotten little attention is there were indications for decades that the city was losing people.

For decades, Memphis papered over the problem by propping up its population with an aggressive annexation program with city government chasing taxpayers as they moved outward in Shelby County. In 1970, there were 623,988 people living inside the Memphis city limits. By 2010, there were 449,930, a 28 percent loss, living in 1970 Memphis. Almost 180,000 people had moved outside those 1970 mcity limits.

After 1970, Westwood, Raleigh, Cordova, Countrywood, Hillshire-Stonebridge, and dozens of pockets of unincorporated areas were annexed, preserving the overall population. Its 650,100 population in 2000 even fooled the Brookings think tank which commended Memphis for keeping its population stable.

It assumed Memphis was like many other cities, landlocked by surrounding towns and managing Memphis from shrinking. For example, St. Louis is frozen in place by 86 municipalities in St. Louis County. Louisville has 96 cities in Jefferson County, Indianapolis has 16 cities in Marion County, and in Fulton County, Atlanta is surrounded by 15 cities. By comparison, local government here is much simpler with seven cities including Memphis and 300 square miles of unincorporated area. Through annexations, Memphis doubled its land area but that came to a hard stop 10 years ago when the Tennessee Legislature blew up the state’s law that allowed the city to have unbridled annexation by requiring the consent of the residents in the proposed annexation area to become part of Memphis.

In other words, Memphis’s current boundaries are set in concrete and whether it loses or gains population in the future is up for debate. It is unknown if the prevailing trends continue and if they do, for how long. A report by economic research and strategic communications firm Younger Associates projects more than 176,000 new residents in West Tennessee by 2045 all 21 counties, including Shelby County. Meanwhile, the Tennessee State Data Center at University of Tennessee Knoxville predicts Shelby County will continue to lose population for the next 32 years.

Memphis doesn’t have time for a debate. It can be argued that since 1970, Memphis has been a shrinking city but masked it with annexation. Now, without that option, the task is to determine how to effectively manage a city losing population. Cities like Cleveland, Detroit, Baltimore, and Philadelphia have confronted it with urban innovations, collaborations, and resident engagement to manage, if not capitalize, on changes in the city’s makeup.

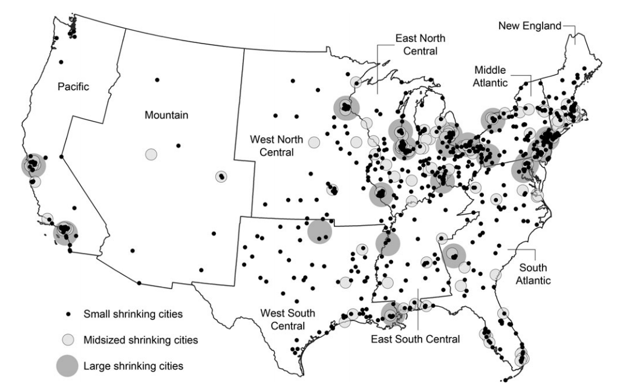

Memphis is not alone. Studies have indicated approximately 40 percent of cities are dealing with population decline, and the good news is that about 30 percent of them are economically prosperous, many by becoming talent magnets.

While business leaders often use population loss as a proxy for fragile economic health, population loss does not condemn Memphis to economic decline in and of itself, and if there is a lesson to be gleaned from other cities, it is that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to population loss. Rather, solutions that work for each city must be organic and appropriate to its trends and conditions.

In other words, if losing population is to become the norm for Memphis, it suggests that city leaders should begin now to plan what that Memphis will look like. What are impacts of a shrinking population or conversely, what is the play to attract new people?

As Chris Clifton advised to a city he knows well: “It’s all about having critical conversations about outcomes and the leadership to take us to our new Memphis.” It’s advice that should summon up a sense of urgency to get that conversation under way sooner rather than later.

**

Join me at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram where these blog posts are published along with occasional articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

Memphis’s largest issue is that we do not have a well connected metro. Unlike other cities that have lost copious amounts of their peak population (take Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, etc.) many people have not just move to the outer rings but have moved away from the area altogether. The metro areas of each of the cities I mentioned above all continued to grow its metro population despite a shrinking city, allowing each to retain some level of economic success and a hope for how its future could continue. We are in a unique geographic and historical area, where both issues work against the prosperity of the city without significant intervention. Without building a strong regional coalition, this area will wither.

Thanks, Trenton, for your comment. You are exactly right. I have written blog posts that completely agree with you, and add this nuance: Memphis is also different from the cities you mention in that as you leave the core county of the MSA and travel outward, key economic factors like income and educational attainment are less than Shelby County (except for DeSoto County). That is different than the cities you cite and as a result, those cities benefit from the higher incomes and talented workforce that support a vibrant regional economy and accrue to their advantage.