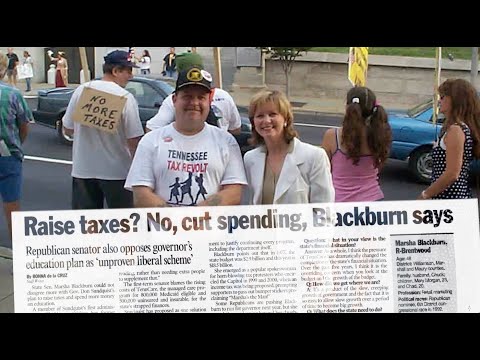

U.S. Senator Marsha Blackburn is taking victory laps about her 2001 role when she was a state legislator in killing consideration of an income tax for Tennessee.

Left unsaid is the fact that she incited a small riot in the state’s Capitol to get her way, by dynamiting the norms of legislative deliberations, by betraying the governor who had given her the job as state film commissioner that she leveraged into election to the Tennessee Legislature, and ensuring the state has one of the most unfair tax systems in the country.

It came at a time when state legislators, at the urging of Republican Governor Donald Sundquist, were considering an income tax as one way to address the nine-figure budgetary crisis confronting State of Tennessee at the time. It had been a proposal raised by Sundquist’s predecessor, Ned McWherter, and with no good options for balancing the state’s budget, state officials had essentially backed into the income tax as an option.

It was a show of political courage by Sundquist, a conservative Republican governor who would dare to consider that the income tax might be the path to more accurate projections of state revenues and to installing a fairer tax structure, meaning that the tax burden is graduated based on income and people who earn more pay more. This is the opposite of the existing tax structure which calls for those with the least to pay the most.

This upside down, regressive tax system remains in place in Tennessee, forcing local governments to rely on sales taxes and property taxes, both of which are regressive, as primary sources of revenues.

The Worst Kind of Elected Official

Unfortunately for Sundquist, a few years earlier, he had jump started Blackburn’s career in government when he named her in February, 1995, as executive director of the Tennessee Film, Entertainment, and Music Commissions, where she stayed for two years and used as the platform in 1998 to run and win an election to the Tennessee Senate.

As Sundquist regularly pointed out in years after he left office, his lapse in judgement was rewarded when she led a mutiny against him. In his words, she represented the worst kind of elected official, a grandstanding, holier-than-thou opportunist, and a politician who would do and say absolutely anything in her pursuit of power.

On July 13, 2001, her behavior that is now commonplace surfaced when she triggered an angry, anti-tax mob to descend on the Tennessee Capitol. Today we would place it in the context of several similar events in later years in states like Michigan and the ultimate of its kind, the January 6, 2021, attack of the U.S. Capitol.

Arguably the father of the modern Republican Party and certainly the Republican Party of Shelby County, Lewis Donelson has urged several Democratic governors to push for an income tax, and in his second term, Sundquist was ready to dismay his GOP base and consider it.

Venerable political reporter Jackson Baker reported in Memphis magazine that Donelson believed “strongly that the state sales tax that Tennessee relies upon is inherently regressive, penalizing the least among us for the sake of the more powerful, and stunting the state’s economy.”

The Riot

Donelson was right but Blackburn lit the fuse that exploded in the middle of deliberations by her colleagues in the state legislature. Rather than engaging in the debate and normal course of business, she instead fired off emails to far right talk show hosts that they needed to mobilize the public to drive to the Capital to right against the income tax.

The talk radio shock jocks whipped up by Blackburn in turn whipped up the crowd by claiming falsely that the proposed income tax would gobble up to half of their incomes. That was despite studies and charts that showed that the income tax would in turn reduce sales tax to the point that Tennesseeans would have a lower overall tax burden.

As a result, in the middle of their session, legislators were impeded in their negotiations by a throng of people – the Los Angeles Times reported there were 2,000 in the mob – who overwhelmed law enforcement and roamed Capitol hallways, harassing, berating, and shoving anyone recognized as a legislator, and causing damage as they pounded on locked doors.

They trapped legislators in their chambers with screams of “thieves” and waved signs reading “Tax Revolt!” and “No Income Tax.” Rocks were thrown through office windows, including the governor and the house speaker. A state employee trying to lock a door against a pushing mob injured his hand.

Overwhelmed by the size and vitriol of the crowd, the Tennessee Legislature adjourned. The income tax was dead. The no new taxes outrage would produce another state budget that failed to adequately fund services needed by Tennesseeans by several hundreds of millions of dollars.

We Versus They

Marsha Blackburn had gotten her way.

Legislative norms, collegial conversations, and loyalty to the process were discarded, contributing to a “we versus they” approach that would metastasize in coming years. spelling the demise of the Democratic legislative majority and fueling the outrage machine that Blackburn would use to catapult into the U.S. Senate.

Lost in the aftermath of the pitched battle was the answer to the ultimate question: would Tennesseeans be better off and pay less in overall taxes with an income tax.

Today, Tennessee is one of only seven states that do not have individual income taxes, and conversely, our state has the second highest sales tax average in the U.S. The average for Tennessee is 9.55%, and first place is held by Louisiana at 9.56%.

One justification for defeating the income tax was that passage would drive people out of the state. Our own experience in Shelby County undermines that argument. After all, Mississippi has an income tax of 4.7% for income over $10,000, and despite that, DeSoto County has benefited from a huge out-migration of Memphians.

For example, DeSoto County’s population is 193,247 – three and a half times more people than the 53,930 in 1980. Its sales tax average is 22nd among the 50 states.

Higher Taxes For Those Who Can Afford It The Least

It is a simple case of cause and effect. If you cut government revenues in one place, the effect is to for increases in revenues in another place. Cutting income resulted directly in dependence and increases in Tennessee sales taxes.

What rejection of the income tax enshrined in Tennessee – and ratified later with a constitutional amendment prohibiting an income tax from ever being enacted here – institutionalized the regressivity of our state tax structure.

One fact says it all: Tennessee has the third most regressive tax system in the U.S. It means that the lowest income families pay three times as much of their incomes in taxes as the wealthiest 1%. It also leaves governments in Tennessee, including the ones in Memphis and Shelby County, with a heavy reliance on sales taxes, property taxes, and fees, which is what makes the tax system so regressive in the first place.

Put another way, when politicians brag that Tennessee is a “low tax state,” they are basing that on our lack of a state income tax but what they are really saying is it’s a low tax state for higher income families.

State government’s own Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations wrote in 2007: “In other words, not only do the rich, on average, pay a lower effective state and local tax rate than lower-income people, they also collectively contribute a small share of state and local taxes than their share of all income. This limits states’ ability to raise revenue, particularly as inequality increases. Research shows that when income growth concentrates among the wealth, state revenues grow more slowly, especially in state that rely more heavily on taxes that disproportionately fall on low and middle-income households.”

Here’s the tale of the tape -state and local taxes paid as a share of income for non-senior residents, Tennessee:

12.8% – Lowest 20%

9.4% – Middle 60%

3.8% – Top 1%

**

Join me at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram where these blog posts are published along with occasional articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.