Antonio Adams has seen it firsthand.

That’s why he’s so passionate about City of Memphis policies that have approved projects but failed to calculate – much less budget – for their life cycles with future costs of maintenance, upkeep, and improvements.

He’s watched local governments issue 30-year bonds for a project or infrastructure without a single question about whether it will need additional funding in the ensuing decades before the bonds are paid off.

He’s seen it in the rushed approval of development or infrastructure because of the promise of immediate fees and more property taxes. It’s a decision that’s made on the basis of the quick cash deposited into local government budgets in the near-term but with no thought about the long-term liability that comes with it.

Before Mr. Adams became city government’s chief operating officer, he was director of General Services, a job that put him in charge of 300 public facilities and overseeing 3,000 acres of parks. Rarely a day went by that he was not confronted with the challenge of significant deferred maintenance or needed improvements without the budget to address it.

Risky Short-Term Thinking

For him, Mud Island is the poster child for this kind of thinking. It’s a 42-year-old reminder of city government’s tendency to chase magic answers but when money was approved for its construction way back when, there was no projection of long-term financial needs for maintenance and upkeep, leading to its deteriorating condition today and even higher capital obligations for city government.

But more than a model of short-term thinking, Mud Island conjures up Memphis’s inclination to chase big ideas backed by an obligatory economic impact study that strains credulity while promising a big pay day.

The latest example of that seems to be Liberty Park.

In retrospect, it’s clear that the grand plans and the massive private investment required for it to be self-sustaining may be as elusive as a serious awareness of how the High Five entertainment venue can be the answer to 155-acre Liberty Park when Memphis’ experience with an identical “entertainment center” at the original Peabody Place project failed spectacularly.

City of Memphis recommends a 30-year contract with High Five with possible extensions of 40 more years. In endorsing this first private development at Liberty Park, it was said that High Five would generate $7 million a year, which would in turn produce about $650,000 for the Tourism Development Zone.

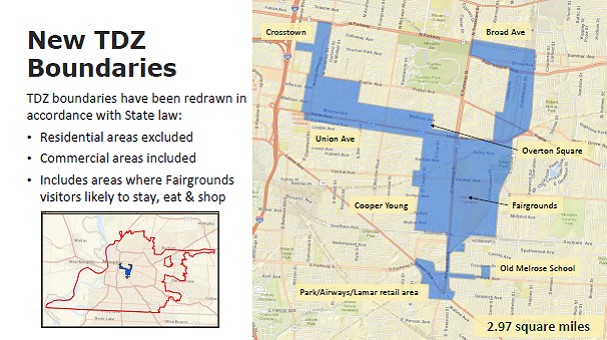

However, that may be misleading. That’s because the amount of new TDZ revenues is calculated by first determining the current amount of sales tax revenues collected in the 2.97 square mile zone and then multiplying that amount by the percentage of countywide sales tax growth and adding in that amount. Only then do you have the answer for how much new TDZ revenues you have to pay off the bonds for Liberty Park.

In other words, the higher the increase in countywide sales taxes, the greater it will cut into the $650,000 attributed to High Five. Meanwhile, this year, payment for the $103.2 million in bonds for the new Memphis Sports and Events Center comes up short by $1.7 million and the City of Memphis faces an increase in the annual bond payment from $2.3 million to $3.4 million in two years.

Gambling on the Future

What’s also as risky as the amount of TDZ revenues produced by High Five is whether it can be an attractor for the quality retail tenants that Liberty Park envisioned in its original planning and that are needed to generate enough sales taxes to pay the annual bond payments. And if City of Memphis has run true to form, it’s moved ahead on the decades-long lease without getting a Dun & Bradstreet report to test High Five’s financial capabilities.

Back to the original point of this blog, the question is also if City of Memphis has conducted a long-term analysis of future financial requirements for the massive sports and event center’s life cycle.

The original 2009 plan for the Fairgrounds, aka Liberty Park, was for the commercial development to be on the order of a shopping center comparable to Saddle Creek in Germantown with national brand retail. It’s questionable that kind of retail will see its future as being adjacent to High Five.

In a sentence, Liberty Park may need to be patient – even if it means decoding some difficult financial realities in the short-term – and execute a bolder vision and higher standards for Liberty Park. After all, City of Memphis needs to make the wisest possible decisions since it is investing marquee real estate along one of the city’s most prestigious streets, Central Avenue. It feels like another case of Memphis pursuing a quick fix rather than waiting for the economy to improve to the point that major retailers are making investments in projects like this one, creating the kind of community asset that Memphis will be proud of in 50 years.

As for the tourism development zone, one reason for its revenue shortfalls is because its original revenue projections included the expansion of Kroger and the undeveloped Overton Square. Both would produce significant new sales taxes but ultimately the full impact was lost when City of Memphis delayed approval of the so-called youth sports facility at the Fairgrounds until after both had been constructed.

Needed: A Policy for the Long-Term

But I digress. Back to the point of this blog post, short-term thinking and short-term funding have resulted in widespread deferred maintenance needs. Mud Island may be a stark example, but it is hardly alone.

As for Mud Island, it’s reached the point that without a clear plan, it really makes no sense to spend the large amounts in capital funding required from the City of Memphis if the aim is to return it to its 1982 condition. After all, time has not been kind to Mud Island, and not just related to deferred maintenance.

More to the point, its uses are outdated, its amphitheater is a dinosaur in the world of venues and a better venue could well be on the south end of the island, and the real estate’s future is unclear but its highest and best use remains to be discerned. Rather than look for yet another quick fix, patience is a virtue when it comes to Mud Island, particularly as long as City of Memphis’s position is that it’s looking for private investment to make it happen.

The reality is that with little budgetary flexibility, deferred maintenance for City of Memphis buildings, streets, parks, community centers, libraries, Mud Island, and more is relegated as a lower priority for City of Memphis.

Without a complete inventory of all the deferred maintenance needs, it may feel insurmountable for the Young Administration and City Council as it shifts its attention from one pressing problem to the next without a plan to tackle what is likely a price tag of several hundreds of millions of dollars.

Despite that, it’s a good time for the City of Memphis administration to set in place – with City Council official approval – an official policy that states that no new project in Memphis will be approved without an accompanying evaluation of impact on future budgets in deferred maintenance and other life cycle factors.

Sprawl Was Not Growth

Arguably the starkest example of this short-term thinking isn’t found just at City of Memphis, but at Shelby County Government, which went to the brink of bankruptcy to fuel financially unsustainable sprawl. It paid for major infrastructure and schools under the delusion that the historic out-migration of residents from the city’s traditional urban core was actually growth. This delusional sales pitch was backed by business leadership and the Chamber of Commerce which praised this illusion of growth and encouraged an accelerated schedule of annexations by City of Memphis.

Incredibly, as Memphis pursued new territory in its chase to grab up former Memphis taxpayers, it was never presented as a choice, say, do we spend hundreds of millions of dollars on sprawl or do we invest within the traditional city borders to enhance quality of life and protect neighborhoods from decline and lower densities?

It is the greatest irony that the rush for spawl meant that its costs were being borne by the neighborhoods left behind. It was the taxpayers in the core neighborhoods that were in essence paying for the decline of their own neighborhoods. The three decades closing out the 20th century was a time when 170,000 people – almost the population of Chattanooga – moved out of the 1970 city limits of Memphis, cutting densities in half and driving up the costs of public services for neighborhoods that were more sparsely populated.

In Shelby County Government, when a handful of brave planners questioned the wisdom of the genuflection to sprawl and pointed to its unsustainability, their opinions were summarily dismissed. (There were politicians’ considerations that trumped all logic but that’s a subject for another time.) The planner’s rejection even included a time when they tried to mitigate the impact of sprawl with a study about Germantown Parkway. It urged more New Urbanist kinds of development and a rejection of the strip mall mentality.

Shelby County Board of Commissioners adopted it as official policy but before the ink was dry on the recommendations, commissioners were approving zoning and developments that flew in the face of good planning, delivering the ugly stretch of highway that is there today.

Plenty of Blame To Go Around

That said, all the blame should not rest with Shelby County Government because regulations at the time gave city government the authority to approve or disapprove of developments within five miles of City of Memphis boundaries. Unfortunately, City Council rubber stamped request after request, going for the short-term gain rather than casting votes based on what was best for the long-term and better city character for the future.

And yet, it was not only that Memphis and Shelby County Governments never treated sprawl as a choice, never discussing the dire implications on core Memphis neighborhoods and local government.

Choices matter and it appears that if Mr. Adams has his way as COO, he will call for more discussions of life cycles, deferred maintenance, and smarter decisions about the long-term rather than the short-term. Hopefully, unlike in the past, there will also be someone – maybe the mayor and city planners – who will lay out what Memphis should become in the future and the policies to take it there.

**

Join me at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram where these blog posts are published along with occasional articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

Yes, blame for the toxic sprawl which has doomed Memphis/Shelby for some time goes to both City and County. In 2000 I had a bright intern who mapped the city’s infrastructure spending. It was ALL spent on the outer ring and could be summed up by saying ‘ widen all of the roads leading out of the city to 7 lanes and build new sewer systems into the bean fields in order to facilitate flight’. As you said, the leaders of both governments thought incorporating spawl was the only way for us to grow- they were exactly wrong. We will pay for that mistake for a long time.

Seeing as High-5 is essentially another version of Main Event and Dave & Busters (and overlaps with a few, smaller local businesses), to what degree will it attract new spending to the city as a whole and what percentage will be reallocating existing spending to the TDZ? This runs full circle with the concept of holistic considerations- robbing Peter to pay Paul- which is directly related to the city’s ability to maintain investments over the long-term.

Steve: Great point. Shelby County suffered from a topography that led to unbridled extensions of the sewer system. It was so inexpensive that it fed the myth that sprawl was growth.

Anonymous: You are so right. Is High Five creating new economic activity or simply moving existing economic activity to that location is the kind of question that I’ve only seen asked once – when city and county were considering the agreement with the Grizzlies to move here? The Chamber of Commerce issued an economic impact study that said that the team would create something like $1B in impact. Instead, county government asked U of M researchers to answer the more nuanced question – how much new economic impact would the team produce after removing the shift in some revenues from other activities/restaurants/events?

Also, I got this relevant email from a reader: And cost-efficient maintenance begins with maintenance-savvy design. We learned decades ago not to put fences in parks because they double maintenance costs. You have to weed-eat the fence line every week during summer. Pick trees that don’t create root problems for machinery. Watch what you plant. On Central Avenue they added a median strip along by U. of M. and planted Crepe Myrtles. Everyone knew they ‘d have to pull them out because you couldn’t see students crossing among the trees. Sure enough, they did pull them out a couple years later. Common sense would be a good starter.