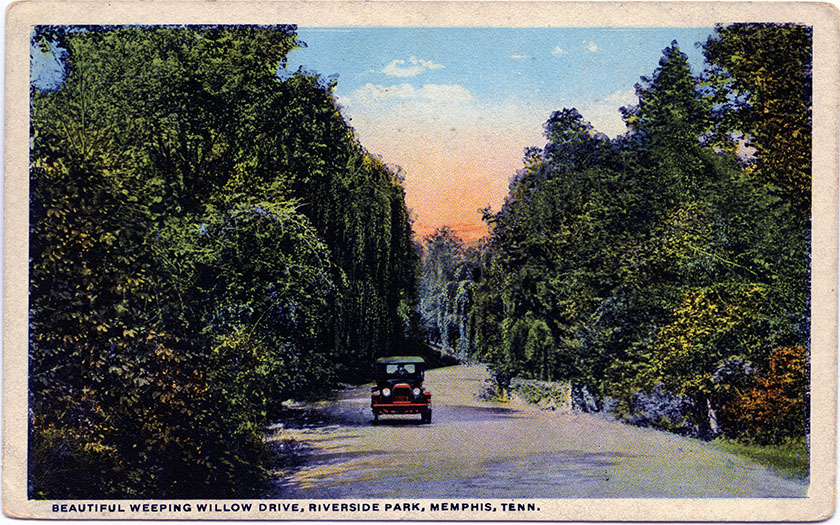

Photo: Postcard of Riverside Park circa 1925

The Young Administration’s recently announced riverfront comprehensive plan has something special in it – the often overlooked, regularly undervalued Martin Luther King Jr. Riverside Park.

When it was just called Riverside Park, it was one of the original grand parks in the “Parkways Strategy” that led to its development along with the parkways and Overton Park, but it has traditionally received less emphasis than its midtown sister.

When it opened 121 years ago at a time when African Americans were forbidden to visit it, it was a destination for White day trippers seeking a journey to the country. Today, its isolation discourages the kind of popularity it deserves and the underwhelming website of the City of Memphis Parks Division does nothing to help out (but then it does little to make any park a must-visit).

Shifting demographics led the South Parkways artery to Riverside-MLK Park to become homes to some of Memphis’s proudest African American neighborhoods; however, the park’s location – divided from “mainland” Memphis by I-55 in keeping with the myriad highway designs that divide African American neighborhoods – and with the Valero Memphis Refinery for gasoline, diesel, and jet fuels crowding it on the south, it’s likely that a large percentage of Memphians have never visited MLK Riverside Park which is 37 acres larger than Overton Park.

Hopefully, the comprehensive plan will develop some strong recommendations to activate the park – which the parks division’s uninspiring website says has a marina, playground, lake, ball field, two tennis courts, 1.2-mile paved walking trail, restrooms, benches, and three pavilions with picnic tables, grills, and benches – and develop stronger connectivity to nearby neighborhoods and the city at large.

The following is my blog post from May 25, 2016 – Finding The Park That Martin Luther King Riverside Park Wants To Be:

The following is my blog post from May 25, 2016 – Finding The Park That Martin Luther King Riverside Park Wants To Be:

The Overton Park greensward parking controversy is a potent reminder of the passion that Memphians feel for their “Central Park,” the centerpiece for one of the most enlightened chapters in the city’s history, the one featuring two great parks and Memphis’ grand parkways.

That they were conceived 114 years ago makes them Memphis’ most elegant testament to the power of visionary city planning and should put them at the top of the city’s bragging rights. And yet, regularly overlooked when we talk about this progressive chapter in the city’s history is that it also produced Riverside Park, now Martin Luther King Riverside Park.

But it’s not just overlooked in the retelling of the history of Memphis parks and the parkways. Its potential has been overlooked almost from its birth, and it presently only hints at what it could be.

But first, the history.

The parks and parkways plan involved two of America’s most famous planning names, Olmstead and Kessler. As the 19th century drew to a close, city government entered into a contract with John C. Olmstead, son of famed park designer Frederick Law Olmstead Sr., and he provided advice on how the parkways could connect two sites, one on Riverside (Cow Island) Road south of the city and another at Lea’s Wood, a virgin forest on the eastern edge of the city. The land for the parks was purchased in October, 1901, and the parks would become Riverside Park and Overton Park.

Greater Memphis Movement

The parks and the parkways were in turn designed by pioneer urban planner and landscape architect George E. Kessler of Kansas City, who, during his 41-year career completed more than 200 projects and 175 plans, including 26 park and boulevard systems. When he began his work in Memphis, he was also creating the master design plan for the Louisiana Purchase World’s Fair in St Louis of “Meet Me in St. Louis” movie fame.

The City of Memphis’ 445 acres at the Wilderberger Farm became Riverside Park, whose construction moved more slowly than Overton Park’s. Upon its opening in 1903, it was considered remote and largely inaccessible, requiring a four-mile carriage ride from Memphis or a 20-minute trip by river steamer, according to the Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. There are stories of daylong excursions by steamer to Riverside Park where families took picnics and ate them overlooking the Mississippi River.

As part of Mr. Kessler’s work over 13 years, he also redesigned three of Memphis’ four 1819 public squares and designed three small parks – Forrest, Confederate, and Gaston Parks. In total, by 1906, when the parkways were officially completed, Mr. Kessler had designed, developed, and opened 1,750 acres of parkland for Memphis in one of the earliest efforts to apply modern comprehensive urban planning and design principles in the South.

Memphis’ motivation for all this park development was its desire to rebrand Memphis in the wake of its devastating Yellow Fever epidemics and loss of it city charter. As the 20th century began, the city had quadruped its size through annexations and the parks and parkways were part of a progressive civic agenda, ushering in what is now considered the city’s Gilded Age and what was called at the time the “Greater Memphis Movement.”

Memphis’ motivation for all this park development was its desire to rebrand Memphis in the wake of its devastating Yellow Fever epidemics and loss of it city charter. As the 20th century began, the city had quadruped its size through annexations and the parks and parkways were part of a progressive civic agenda, ushering in what is now considered the city’s Gilded Age and what was called at the time the “Greater Memphis Movement.”

A Parkways Strategy

Mr. Kessler’s original concept of meandering boulevards around Memphis evolved into a rectilinear design that incorporated and improved existing streets. At the terminus of the parkways at Summer Avenue northeast of Overton Park, he measured out a mile “speedway” for buggy racing, but that was put to a stop when the public pressured officials into enforcing a speed limit on the entire parkways system as automobiles became more prevalent – there were about 1,000 by 1910. (Most Memphians traveled aboard the extensive trolley system, Memphis Street Railway, which ran 150 cars daily over 109 miles of tracks.)

In an early demonstration of the power of smart planning, Overton Park and the parkways soon became among the most desirable residential areas in Memphis, according to Beverly Bond and Janann Sherman’s Memphis: In Black and White. There’s no reason something similar, a “Parkways Strategy,” could not have the same effect today, attracting people into Memphis, particularly middle class families. It was a fact of life that African Americans were excluded by government policy from these popular areas at the time, denying them the wealth accumulated by white families in the form of real estate. Today, a Parkways Strategy could be a way to strengthen, stabilize, and rebuild areas and increase wealth for all Memphians.

From the beginning, Riverside Park was a lower priority than Overton Park, and Mr. Kessler was pressured by City Fathers (the term was especially apt at that time) to concentrate his attention on the eastern park. As a result, it quickly became a showplace with bridle paths and a bandstand for nightly concerts at dusk. A golf course was added in 1904 and a meager menagerie made up the zoo when it opened in 1908, having evolved without any city planning.

African Americans were forbidden from visiting the zoo or using the parks. Following the collapse of Reconstruction and as the population increased after yellow fever, African American elected officials, police officers, and school board members elected in 1870s and 1880s gradually disappeared as the Democratic Party built its resurgence on a foundation of white supremacy and disenfranchisement.

Letting the Park Be What It Wants To Be

We say all this to emphasize the point that South Parkway and Riverside Park were not beacons of African American wealth or recreation. African Americans were forbidden for more than half a century buying property or visiting the park. It is one of the chief ironies that South Parkway today traverses some of Memphis’ most durable and proud African American neighborhoods, and Riverside is largely off most people’s map because of its location, which pretty much eliminates an accidental discovery of the park’s surprises. Even with directions, it can be a challenge.

Riverside Park never received the attention that Overton Park got, and it was said in the early 20th century that the intention was to make it a nature park. We suspect that it backed into this description because the money and attention were being focused on Overton Park, which was seen as doing more to drive revenues and population growth.

At any rate, the inattention to Martin Luther King Riverside Park today, a century later, seems a tradition built over the intervening decades, and it’s hard to detach its treatment from the same lack of attention given to area neighborhoods. Today, it remains unprogrammed, facilities feel perfunctory, and yet, it is arguably Memphis’ most spectacular park setting.

The most direct route from downtown is south on I-55, exiting at Mallory Avenue. About the time you think you’re driving into Valero Memphis Refinery, there is an entrance just to the right that takes you into the Martin Luther King Riverside Park. The northern entrance is at Riverside and West Person, and again, you may need a compass to find it. Regardless of which entrance you choose, you need directions because there are no signs on the highways to tell you that there is a nearby park 37 acres larger than Overton Park at 379.32 acres (we don’t know what happened to the missing 65.7 acres purchased by City of Memphis 115 years ago). (Since posting this blog post, we received a note explaining that the “missing” acreage – the difference between the land bought by the city originally and the land now within the park – was because City of Memphis sold the land in the early 1990s to Valero for parking. The emphasis of parking over parks goes back farther than we thought.)

A Rich Chapter In History

When Riverside Park opened, it overlooked Presidents Island, which then really was an island in the Mississippi River. It all changed in the late 1940s when the riverfront park became a lakefront park, resulting unsurprisingly from the work of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who led development of an earthen dam 6,800 feet long, six million cubic yards of industrial fill, a pumping station, and a levee.

When they were through, the island had been turned into a peninsula, and the Mississippi River had been replaced with McKellar Lake, a deep water harbor that is overlooked today by Martin Luther King Riverside Park. As was often the case with Corps of Engineers’ projects, it today appears more like a monument to the glory of engineering than smart planning.

That doesn’t mean that Presidents Island doesn’t have a rich and interesting history that opens a window into Memphis history, and it should be explored in historical exhibits at the park. In 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau used the 10,000-acre island as home for freed slaves and 1,500 former slaves stayed there until they were absorbed into the community. Years later, the infamous slave trader and Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest contracted to establish a penal farm there to raise corn and cotton. Shelby County Government paid him 10 cents a day per inmate in return for his supplying food, clothing, and housing.

In 1877, Forrest died of dysentery from drinking impure water, and while no one knows precisely the source, it is possible, in a burst of karmic justice, that he got the impure water on Presidents Island. Unsurprisingly, there were reports of prisoner mistreatment and a grand jury recommended changes in the penal farm’s operations. Upon Forrest’s death, his son, William, signed a new contract. It seems poetic justice that in 1968, City of Memphis voted to add Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s name to the park’s official name.

Beyond Good Enough

In 1878, during the Yellow Fever epidemics, Presidents Island was a refuge for people fleeing Memphis, and a quarantine camp was set up there as well. Later, it was a site of large and small farms raising corn, cotton, soybeans, cotton, hogs, chickens, and turkeys. Enough farming was still under way in 1950 that a one-room schoolhouse was built.

One more note: During Prohibition, the island was a refuge for moonshiners and the smoke from stills was a regular feature for observers in the park.

We say all of this to make this point: Martin Luther King Riverside Park is a window into an interesting chapter of Memphis’ history and offers a rich opportunity to be a “cultural and historic park” that tells the story of a river city through markers, apps, oral histories, and more.

That said, for Martin Luther King Riverside Park to become what it should be, it will need more attention than the Division of Parks can deliver at a time when city budgets are stretched thin and when outside imagination is needed to reach, in the words of Hyde Foundations chair Barbara Hyde speaking about Shelby Farms Park, beyond the “good enough for Memphis” attitude to find out what the park wants to be.

A Different Approach

Shelby Farms Park Conservancy, Overton Park Conservancy, and Memphis River Parks Partnership (a partner in the new riverfront comprehensive plan) have proven the power of a different approach to expanding park aspirations and to delivering on a vision to be the best that public space can be. Perhaps, what is also needed at Martin Luther King Riverside Park is a conservancy that brings the best of public and private sector thinking to this historic, great Memphis park.

Martin Luther King Riverside Park is a product of Memphis’ greatest chapter of city building, the one that produced the parks and parkways, and it can be so much more than it is today. Walking through the park, it is easy to imagine what it can be.

And in keeping with the park’s history, Mr. Kessler inspires us. He wrote: “While parks are of inestimable value in making a city inviting to desirable residents and visitors, furnishing pleasant drives to those who can afford these luxuries, adding to the value of real estate, and promoting the general prosperity, these are matters of small consideration when compared to the imperative necessity of supplying the great mass of the people with some means of recreation to relieve the unnatural surroundings in crowded cities.”

We have the distinct feeling that Mr. Kessler would tell us that Martin Luther King Riverside Park was never finished, and there’s no time like the present to do that.

***

In early 2010, Josh Whitehead, former planning director for Memphis and Shelby County Office of Planning and Development, wrote three posts for us that were a fascinating tour of the parkways. You can read them (we apologize in advance for the formatting):

South Parkway:

East Parkway

North Parkway

***

Join me at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram where these blog posts are published along with occasional articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.