When Rick Masson, Robert Spence, and I negotiated the agreement to bring the Grizzlies from Vancouver to Memphis, it often felt like there was an unseen third party in the room.

We would come to an issue that we considered nonnegotiable. We would draw a line in the sand. After gnashing of teeth, if not raised voices, the Grizzlies’ team would grudgingly make a concession and agreement would be reached.

Or at least that’s what we thought.

Despite thinking that we had settled a contentious issue, the Grizzlies would return to the negotiating table and blow up our agreement by saying, “The NBA won’t agree to it.”

We had no direct communications with the NBA so we were at the Grizzlies’ mercy on what they said, but the end result was the same: it blew up the agreement that had been reached and we never even got to hear it directly from the NBA.

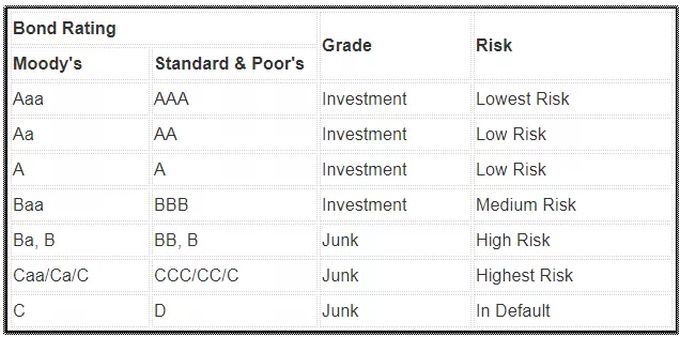

Bond Ratings Aren’t About The Public

That must be how City Council and County Commissioners feel at times during budget hearings.

It’s not unusual for CFOs, in the midst of questions about budgets, to bring discussions to an end by saying something like “our bond rating agencies think…” or “our bond rating could decrease our rating if you do that.”

In this analogy, rating agencies are to local government what the NBA was to Grizzlies negotiations: an unseen party whose opinion is considered definitive. CFOs are the conduits for information and quotes attributed to rating agencies which just happen to support the CFO’s own opinions or position.

But here’s something else that’s never said: bond ratings aren’t about taxpayers. They’re about bond buyers.

Another thing you’ll never hear: despite mayors’ speeches and budget presentations, bond ratings are not THE definitive indicator of smart financial management.

That doesn’t mean that they mayors won’t say again that the bond ratings is confirmation that his administration’s emphasis on core services is working.

The City of Memphis online data hub even lists the yearly bond rating as if it’s a critical measurement of strong financial management; however, it has not been updated since 2021. It lists Standard & Poor’s rating for City of Memphis as AA and Moody’s at Aa2 (both agencies can give higher ratings for municipal bonds).

If anything, bond ratings are to government financial management what Wall Street is to the economy. And like Wall Street, they work in the interest of investors.

Fooling Local Government

Charles Marohn, president of Smart Towns, has said it well: a bond rating “says a lot about where a community is in its life cycle and very little about its management. It doesn’t say anything about how the city analyzes the viability of projects. It says nothing about its financial productivity or return on investment. It doesn’t even say anything about the quality of life there and whether people will want to stick around once the sheen wears off.

“That’s because the ratings agencies don’t care about any of these factors. I’ve met with them and, while the people that work there and do these analyses are smart and interesting, they work for investors. They don’t care if the pipe in the ground doesn’t support enough connection to retire the debt to put it there. They don’t care if the road is really expensive to build and won’t yield anywhere near the tax base needed to sustain it. They don’t care that each new subdivision the city does puts it deeper in a financial hole.

“All they care about is the community’s present capacity to retire new debt.”

The rating agencies aren’t interested in the fact that in Memphis concentrated poverty is intractable, that at least 32,000 affordable houses, that wages are too low, and personal incomes lag. Their concern is only if the bond buyers will be paid back.

“Let’s not let our local governments be fooled about whom they work for,” said Mr. Marohn, who has worked, written recommendations, and spoken in Memphis. They work for the residents, not investors. They should seek the approval of their citizens, not the ratings agencies.”

No Fund Balance Rules

The reputation of rating agencies took a beating after the Great Recession, because they were seen to have culpability in the crisis in the first place. In the intervening years, the methodology and credibility of ratings agencies have been called into question. As a result, bond ratings are no longer the end all, be all for investors, who often see them as a starting point, while CFOs around the country are working directly with investors.

In budget presentations to legislative bodies, the other side of the coin from bond ratings is fund reserves. It too is often used to bring a halt to discussions because of the mystery around how much is needed and how much is too little and how much is too much. The answer regularly and conveniently supports the finance official’s point of view and defies discussion of an esoteric aspect of government operations.

When it comes to the fund balance, rating agencies tend toward more is better, not so much because the fund balance will be there, if needed, during an economic downturn to pay for vital public services, as politicians like to say, but because it ensures bond investors will be paid.

The problem is that when fund reserves are too large, it means governments are hoarding money that could be better spent on neighborhoods.

The sizes of fund balances and the policies to determine them vary across the country.

While some places agonize over removing any money from fund balances, as if it is violating some Golden Rule of public financial management, it’s worth remembering that city and county governments are generally resilient. There was even a time during the Herenton Administration when the fund balance was depleted – and the bond rating did not go down.

Demystifying Terms

While it’s inarguably good for governments to have fund reserves in the event of the so-called “rainy day,” how large they should be is a contentious issue because there is no one answer that works for all governments.

Because CFOs cloak explanations about bond ratings and fund balances in arcane terms and confusing language, whenever they are brought up, they are essentially a trump card for stopping discussions and questions in their tracks.

Local legislative officials regularly accept what they are told about bond ratings and fund reserves, because over the decades, only a couple of them have come from a financial management background and know the questions to ask and how to evaluate what they were being told.

As a result, when the subject of bond ratings comes up and finance officials raise the specter of a downgrade, no one even asks how much more a lower bond rating would actually raise cost for bond payments.

The first step in more productive budget discussions is not to allow the use of financial terms to shut down debate and for budget committee members to conduct their own due diligence to understand not just the meanings of the terms but how they impact city and county budgets and to remove their mystery.

**

Join me at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram where these blog posts are published along with occasional articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

The solution is to get a plan, change internal financial management and get new bankers. But, get a plan first.

Smart City Memphis, with all due respect, I think you got this one wrong.

While investors rely heavily on a rating agency’s credit assessment to gauge the financial health of an entity and to make their investment decisions, City and County bond ratings are absolutely about taxpayers since investor decisions (based upon these ratings) drive the City’s cost of financing capital.

Today, the City of Memphis competitively sold $135 million in bonds to finance capital projects. The Bonds were rated “AA” (negative outlook) by S&P Global Ratings and “Aa2” (stable outlook) by Moody’s (which is the same as last reported on the data hub on January 24, 2024). BVAL, who publishes Bloomberg’s widely accepted market benchmarks, reports that the spread between “AA” and “A” rated municipal tax-exempt rates to be approximately 0.20% today. On today’s bond sale, this difference equates to a total interest expense savings of $2.5 million – a meaningful impact to the City’s resources funded by taxpayers.

The “mystery” of rating agency analyses can be found in their published standard criteria and methodologies. Each of the rating agencies takes a holistic view of the City’s financial position, including management, budgetary performance, financial stability and economy when assessing the credit quality of the City. In fact, Moody’s rating methodology assigns 30% of their assessment to the “Economy” (including resident income and economic growth) noting “A city’s or county’s economy provides important indications of its capacity to generate revenue at the local level.”

And, yes, the rating agency criteria includes an assessment of a city’s or county’s available Fund Balance as a component of “Financial Performance” as indicative of the resources available to fund services and unforeseen contingencies, including, for example, a budget shortfall. The financial stress caused by the global pandemic spotlights an example of the need for these “rainy day” funds to keep our governments running.

Bond Ratings may be about Investors, but Cities and Counties – and ultimately taxpayers – want to obtain the best and highest credit rating possible to attract the lowest cost of capital from these Investors! Bond Ratings are definitely about the taxpayers.

Thanks for the comment, Lisa. Can you answer a few questions: Over what period of time is the $2.5 million savings? What was the term of the $135M issuance? And what was the interest rate? Are the proceeds from the bond issuance to be spent largely on refunding previous bond issuances or is the $135M to finance new infrastructure?

See https://emma.msrb.org/IssueView/Details/9AF5D33F1D034A83A42525E20907F2BA for more details. The Final Official Statement will be posted within a week.

^^ Not Anonymous, from Lisa 🙂

Lisa- cannot thank you enough for providing the link to this information! What a great resource.

“Because CFOs cloak explanations about bond ratings and fund balances in arcane terms and confusing language, whenever they are brought up, they are essentially a trump card for stopping discussions and questions in their tracks”.

Let’s talk about this comment for a moment. I would expect any appointed or elected leader to ask questions if they do no understand the terms or language being used in any situation where it impacts decision making. It sounds like this is less a failure on the part of a CFO or the ratings agencies and more a failure of city leaders to ask questions and understand the subject matter.

Thanks for the link. It’s apropos of the point I was making about CFO explanation. When I selected it, I got this message: No official statement is currently available.

As i mention above, the Official Statement will be available within a week of sale and prior to the bond closing when money is exchanged. The bonds were sold just yesterday, so time is needed to finalize the structure and prepare the documents with final numbers. Please don’t be quick to jump to your conclusions. It is standard timing in the municipal market.

I’m not drawing any conclusions from the message. I’m just asking questions to get more information.

It would be good if City of Memphis put all of the vitals on its website under the finance department.

PS: I used to deal with Marlin Mosby back in the day on bond issuances.

I remember… I learned from the best!