By John Branston

Things could be worse. And they have been, for Memphis and for the country.

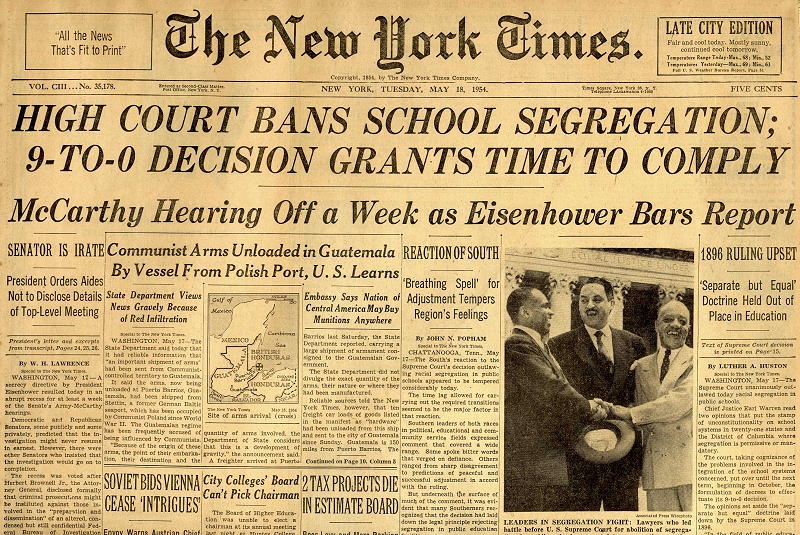

May 17th was the 70th anniversary of the U. S. Supreme Court’s segregation-busting Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision. Coincidentally, I spent a couple of days more or less simultaneously rereading Bruce Catton’s A Stillness at Appomatox and the third and final volume of Shelby Foote’s Civil War narrative. Catton was from my home state, Michigan, and Foote, the gold standard of interviewees and talking heads, from my home town of Memphis.

Both hefty books covered the post-Gettysburg slaughters at the Wilderness, the Petersburg crater fiasco, and Spotsylvania where tens of thousands of soldiers were killed. Even after that, federal generals Meade and Sheridan were keen to keep fighting and on the other side Lee was loathe to use the word “surrender” before yielding to Grant, Lincoln, and his own better angels.

Grim as they were, the 70th anniversary stories and the books were a welcome relief from the screaming on television and sordid updates on the Trump and Stormy Daniels trial. It may well be obscene and bizarre to lump them in the same story, but now as then we are a country divided. Just not as divided as we used to be in 1863 when men fought for keeps with muskets, bayonets, and cannons, or 1954 when separate-but-equal was the law of the land until the Brown decision.

There were actually two Brown decisions. Brown II called for desegregation “with all deliberate speed.”

Which meant slow. In 1958, Gerald E. Young, 8 years old, tried to enter all-white Vollentine Elementary School. He was turned away by, among others, the attendance officer and assistant superintendent backed by local bluebloods on the school board.

In 1960 – a full six years after Brown and Brown II, Dr. Wilson Northcross and the Legal Defense Fund filed suit on behalf of 8-year-old Deborah Northcross. Two years later, 13 first-graders (one returned to his segregated school) integrated four of the Memphis public schools in a grade-a-year plan. Ms. Northcross, too old by then, was not among them although she later graduated from Central High School.

“Desegregation gave whites the impression we wanted to be with them, and that was not the point,” she said on the 50th anniversary of Brown. “It was a matter of school choice and educational equity.”

Integration began in earnest after the Supreme Court’s 1971 decision authorizing busing as a means to change “all deliberate speed” to full-speed ahead. One of the more prophetic statements in the massive court record came from a dissenter on the appeals court bench named Paul Weick.

“The burden of eliminating all the ills of society should not be placed on public school systems and innocent school children,” he wrote.

On the prevailing side was Judge Robert McRae, who tried to go slower than full speed ahead but faster than a grade at a time. After his “Plan A” failed he cut to the chase with “Plan Z” authored by the courageous but unfortunately initialed O. Z. Stephens.

“There would have never been any rest in this city until it was tried,” Stephens said years later. “Plus, the Constitution said we had to.”

A total of 26 inner-city schools were never integrated, either because there were not enough white students to go around or the masterminds figured white students would refuse to attend them. As indeed they did. White enrollment hit the tipping point of 30 percent by 1980, 20 percent a decade later, and is now below 10 percent – most of them clustered in a handful of “optional” schools.

With charter schools, the surrender of the Memphis schools charter, private schools recruiting minority students, and half a dozen municipal school systems bordering Memphis, the menu of education alternatives would have been unimaginable in 1954.

Various and sundry polls, documentaries, books, movies, and news stories will retell the tale this year. But there is a fairly simple way to figure where someone stands on the great issues of the day.

Ask “Do you have children, and where do/did they attend school?”

**

John Branston covered Memphis as a reporter and columnist for 35 years.