Part 1 of this post was published Monday and can be read here:

***

Mass Hypnosis

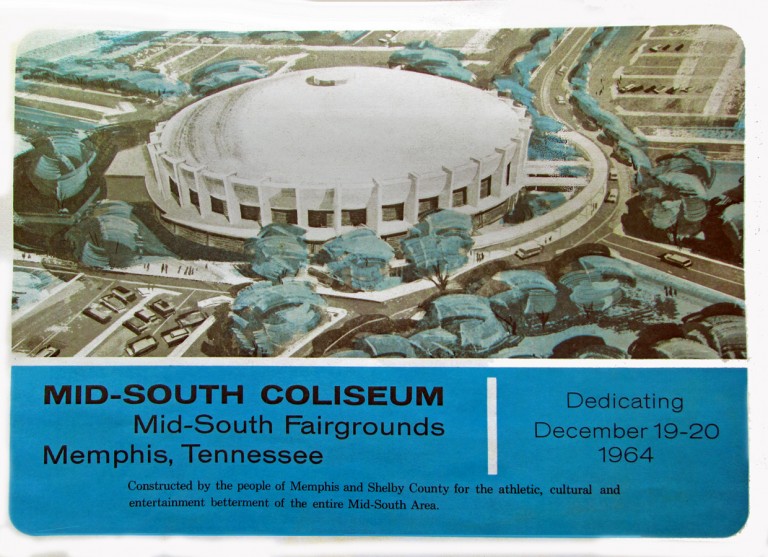

Truth be told, The Pyramid could not compete with the quality of the Coliseum’s construction materials – and certainly not its acoustics – and in retrospect, it’s unbelievable that our gullible community could be convinced by backers in the business community that a “first class, state of the art” arena could be built for $39 million (although the final cost after scope changes was approximately $62 million).

Nor were the new arena’s comfort and sight lines as good as the Coliseum. While the University of Memphis did not want an arena with 20,000 seats, the building’s seating was expanded by several thousands of seats to satisfy one county commissioner whose vote was crucial for approval of the new arena.

With competition between the two arenas, it was no surprise that both ended up losing money, but what was truly remarkable was that the Coliseum managed to hang on until 2006, when it could not comply with the requirements of the American for Disabilities Act (ADA) and city and county governments were not going to pay for it to be compliant.

When the potential of a National Basketball Association team moving from Vancouver to Memphis surfaced, it became glaringly obvious how cheaply the Pyramid had been built. The cost to upgrade it to NBA standards was almost exactly the same as building a modern arena, and with the 2002 memorandum of agreement with the Grizzlies, the community set out to build a new arena.

Closed For Business

Meanwhile, Memphis and Shelby County Governments made sure in its agreement with the Memphis Grizzlies, there would not again be a time when public arenas competed against each other to the detriment of taxpayers. As a result, the governments entered into a non-compete agreement that gave FedExForum priority on all bookings and the arena’s best chance to maximize its revenues.

In return to that proviso and to all predictions to the contrary by pundits, the Grizzlies agreed to city and county demands for it to pay all operating costs of the FedExForum which were estimated at the time to be at least $5 million a year. Even more, if the non-compete agreement had not been signed, it would have likely meant that taxpayers would pay operating losses at FedExForum, The Pyramid, and the Coliseum.

In Nashville, that city’s government paid millions of dollars every year for the operating losses for its National Hockey League arena. Negotiating the non-compete agreement was one of city and county government’s finest hours.

By the time the Coliseum closed for good in 2006, it had languished for several years, and the fact that it managed to stay open longer than the Pyramid is remarkable. (Its closing was part of the City of Memphis’ strict ADA settlement agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice.) After all, at that point, the Coliseum had stayed open 42 years old and The Pyramid had managed to stay open only 13 years before it was obsolete.

Underutilized Public Assets

In 2004, with the move of the Grizzlies from The Pyramid into FedExForum, Memphis Mayor Willie W. Herenton and Shelby County Mayor A C Wharton appointed a special committee to consider jobs-producing uses for the two empty arenas, The Pyramid and the Mid-South Coliseum, and they named Robert Lipscomb, director of Memphis Division of Housing and Community Development and executive director of Memphis Housing Authority, to direct the process.

After public hearings in the early years following creation of the special committee and a report by Looney, Ricks and Kiss about a family-oriented focus, the Tennessee Tourism Development Zone (TDZ) was identified as a funding source that would allow City of Memphis to access more than $300 million in state sales taxes to redevelop the former Fairgrounds site that was acres and acres of asphalt. In time, the construction of Tiger Lane and improvements to Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium were approved with the idea that when the TDZ was approved, City of Memphis would be repaid.

Many effective grassroots advocacy campaigns need a villain and unfortunately for Mr. Lipscomb, he was given that role. After the process to find a better use for the Fairgrounds was about nine years old, the debate about its future was triggered, and in the process, he was vilified and his motives were questioned in ways that make Donald Trump’s comments seem tame. By that time, he had evaluations and reports that the Coliseum could not be repurposed for a revenue-producing use, much less a use than complied with the non-compete agreement.

Contrary to mythology, he had assembled a team and tasked them for more than a year to consider how to save the Coliseum, what the costs would be, and what the uses could be. In fact, in one of the two dozen presentations about the Fairgrounds development that he made to Memphis City Council, there was a time when a majority of that body urged him to ask them to vote to raze the building. He declined, because he still held out hope that someone would step forward with the money and the concept to use it.

Later, in the face of criticisms about the lack of more recent public meetings about the Fairgrounds, a firm was hired to conduct some more and the Urban Land Institute was hired to bring fresh eyes to the Fairgrounds opportunity. In the end, the ULI team could not identify a way to put the Coliseum back into a use consistent with its former uses, recommending the preservation of a part of the building for something akin to a pavilion stage.

Finding A New Future

Various possible uses have surfaced – from a brewery to an events and concert venue to a one-of-a-kind experiential art installation. There is no lack of ideas. The lack is the money to execute them.

Estimates are that $40 million would be required to return the Coliseum to its former glory and that is likely conservative (City of Memphis estimates several years ago put the price much higher). 1) Two significant barriers remain: a concept that would capture the public’s imagination and mobilize a groundswell of support for it to become reality and 2) a financing and fundraising plan that offers realistic potential.

The fact that the Coliseum is still standing and that the Strickland Administration left it standing should be considered progress. That said, the Young Administration is likely to take the same passive approach to the Coliseum.

While some people are hopeful that wording in the City of Memphis agreement for Tourism Development Zone revenues to be used for Fairground redevelopment, it is in truth cold comfort. It does little to ensure the Coliseum cannot be razed if City of Memphis wants the site for another use as the commercial development begins or if the ambitions for youth and amateur sports expands.

Needed: A Realistic Business Plan

Challenges can always surface as quickly as the proposal to tear down the building for a soccer stadium. If the State of Tennessee had provided enough funding for that to happen, the old arena would already have a demolition plan. In other words, there is no promise that the Coliseum can stand in perpetuity so supporters are hoping for a new sense of urgency with creation of the newly formed Coliseum Conservancy.

The Coliseum Coalition has been the grassroots organization fighting to keep the dream of an active, renovated Coliseum alive. It’s unclear why the organizers of the Coliseum Conservancy did not simply join forces with the existing group because the Coalition could benefit from the political and funders firepower that the Conservancy appears to have.

As the Urban Land Institute said, “nostalgia is not a business plan,” so whatever is to come must make sense on a spreadsheet in black and white and be backed by a business plan that guarantees that it can be financially self-sustaining. As history has proven, the Coliseum should not build its future on the premise that city and county government will come to its rescue.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.

In the second to last paragraph: Is it the Conservancy or the Coalition that appear to have “political and funders firepower”?

This 2-part serves as a worthwhile summary. By the time I finished reading, I was left with numerous questions. Why did the Coliseum board go against the Mayors? Were they really so naive as to think they could openly defy elected leaders and yet still recieve the needed, substantial infusion of public funds? Why does there remain a well defined desire to repurpose the building? Is it entirely rooted in nostalgia and/or because the building exists? What was the logic and reasoning at the time for why that exact location was selected?

The Conservancy brings the political and funders firepower. Thanks for asking the question. I’ve clarified that sentence.

The Coliseum board had a strong executive director who convinced the board that she had a plan that would continue to make the facility financially self-sustaining and board members saw the Coliseum as a significant part of Memphis’ history and decided to buck the mayors position on closing. I believe the members were indeed naive in accepting her financial projections and assuming that city/county would step up and fund capital needs and deferred maintenance after being rebuffed by the executive director and board. It was not to be.

I accept the Coliseum Coalition’s sincerity in its belief that a productive use can be found for the building – https://coliseumcoalition.org/.

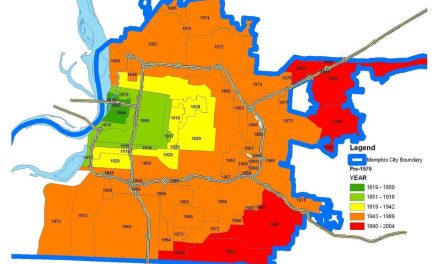

The location that was selected for the Coliseum was seen at a convenient mid-point for most of the city and county. It also was a political compromise between those who wanted it built outside of Memphis and those who argued for a downtown location.

Thank you for the follow-up!

In so many ways, be it access, impact on surrounding neighborhoods and uses, the ability for both the Coliseum and the stadium to be something other than just anchors for convenient parking….. the location compromise has ultimately proven to be a lose-lose proposition.