Some business leaders recently expressed their concern about Memphis’ population loss.

Better late than never.

The truth is that Memphis’ population has been dropping since 1970, and by 2009, I wrote a blog post concluding that Memphis is a “shrinking city.”

Many people like these businesspeople believe that population growth is and of itself a proxy for economic growth. And yet, research has found no connection between the prosperity of cities and either their size or their population loss. More about this in a future blog post.

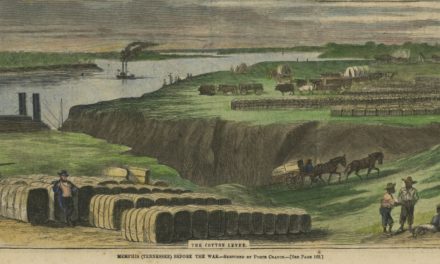

Back to this blog post’s point, take the 1970 city limits of Memphis. The population at the time was 619,757.

Here’s the population within those 1970 borders over time:

619,757 – 1970

568,677 – 1980

528,064 – 1990

500,370 – 2000

445,841 – 2010

449,930 – 2013

Using the 1960 city limits of Memphis as context, the decline in population by 2013 was 41%.

Fooling Ourselves

It’s a decrease in population of 27%, or put another way, 170,000 people moved out of the Memphis of 1970 as they were incentivized by sprawl that was labeled by the media, political, and business leadership as “growth.”

It never was. It was a massive, historic out-migration that decreased Memphis’ density, hollowing out core neighborhoods, triggering the decline of the middle class in those areas, and driving up the costs of the city’s public services.

Over this time, Memphis was like the proverbial frog that slowly boils to death because it doesn’t notice the temperature is rising. Memphis’ political and business leadership seemed oblivious to the demographic realities happening in front of them, and as a result, they did nothing to call attention to reality, instead treating more than a dozen annexations as a reason for celebration.

Their focus was on the new land brought into Memphis rather than on the core neighborhoods being left behind. In the end, both city and county governments were at fault, but Shelby County Government required residents of the urban core were required to pay for sprawl at the expense of their own neighborhood’s decline as sprawl brought the county government to the brink of bankruptcy.

It was the series of annexations created a false sense of security because it kept the overall Memphis population at roughly 650,000. However, while leadership was being lulled to sleep, Memphis needed a plan for a shrinking city rather than rushing headlong to annex more and more land area.

Tough Times

Contrary to conventional wisdom that chalks it all up to Mayor Herenton, the largest exodus took place between 1970 and 1980 when 57,987 people left our city. It was a time of dramatic turmoil in Memphis, reeling from the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The Peabody Hotel was boarded up, Beale Street was in shambles, the Chamber of Commerce flirted with bankruptcy, 17-year-old Elton Hayes died in a ditch after the truck he was driving was stopped by city police and county deputies, and school busing roiled the school district.

It triggered a crisis in city identity and racial understanding. In a ranking of cities who lost middle class families, Memphis was near the top. The underpinning of annexations was Memphis’ pursuit of taxpayers as they moved east and south but also a political strategy based on keeping more white voters in Shelby County.

No amount of annexation is cosmetic enough to prevent the inescapable conclusion that in our pursuit of new taxes, we may actually have escalated the decline of the urban center. Operating on the theory that annexation areas were the sources of much-needed new property taxes, city government took a decidedly optimistic viewpoint of the overall net fiscal effect.

Considering Options

When the 20th century dawned, Memphis covered an area of 18.5 square miles with a density of 7,125 people per square mile. No one would have expected that Memphis should have stayed that small, but even by 1970, it was only at 217.4 square miles (a doubling of the size of the city in about 20 years since 1950).

Today, the size of Memphis are about the size of New York City – 297 square miles to 305 square miles. The overlay of public services over such a massive area stretches already underfunded services even more, and to suggest in hindsight that Memphis needed a serious debate over the relationship between the size of the city and the effectiveness and economy of its public services.

Maybe, just maybe, the optimal size for highly efficient public services and the best quality of life would have come from a smaller Memphis. If not for the Tennessee Legislature changing state law regarding annexation, Memphis might have expanded to almost 500 square miles under the existing annexation reserve agreements with the other Shelby County towns.

It was one of the extremely rare times when legislators intended to take a political shot at Memphis and probably did it a favor. Otherwise, Memphis could have annexed until it was size of Los Angeles.

A New Perspective

The density of Memphis is down to just over 2,000 persons per square mile. That’s down from about 4,000 in 1960, about 3,000 in 1970, and about 2,500 in 1980. Not only are cities more sustainable when they are denser, but public services are easier to deliver economically.

If there is a plan for a shrinking city, it must be more than an accounting exercise. More to the point, it must reach conclusions about what older parts of our city should look like, including the needs of each area and the plans for the city to respond to them.

Most of all, the shrinking city analysis should consider strategies that would improve Memphis’ ability to compete for and retain for 25-34 year-old college-educated workers and middle class families back into Memphis.

Before we begin, we need to set aside the obsession by many about growing the population. Growth at the expense of quality of life means nothing. Growth at the fringe that consumes funds that should be invested in the “old” city is not really growth in its broadest sense.

Getting The Conversation Right

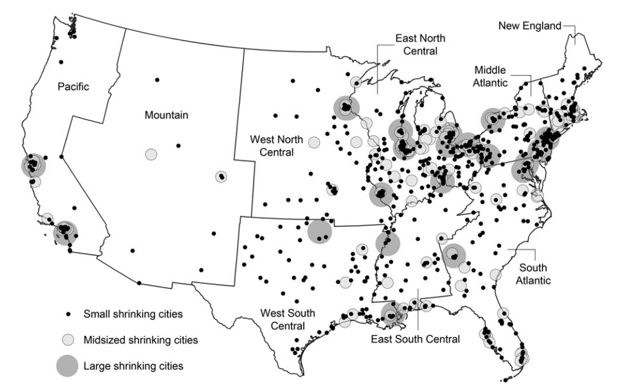

That’s why we believe that Memphis needs to get involved in the shrinking cities discussions. It’s a field of study that may become more and more important in coming years. After all, for every two cities that are growing, three are shrinking.

We may not like the company we will be keeping – Detroit, Dayton, Cleveland and Youngstown, to name but four – but we need to reconsider our definition of success. Cities like Cleveland seem to be failing fast; 115,000 people have left that city in the last decade alone, and cities like St. Louis have lost half the population it had 50 years ago.

So, while we need to look at Memphis in new ways, the dimensions of the problems here have not reached the levels of these Rust Belt cities, and that’s why we need to start this conversation now.

We admit that the prospects of a downsized city may be bruising to our civic ego, but it is nonetheless essential. Just as the slow food movement started in Europe, so did the slow city movement. Its singular message is that a smaller city does not necessarily mean that it is a failing city.

The Time Is Right

In this way, the shrinking city movement is about holding two opposing ideas at the same time – hope and despair. It is in embracing contradictory forces that success may be found, and if any city is to do it well, there’s little reason that it shouldn’t be Memphis, because we’ve built a history on our conflicting character – Beale Street in the Bible Belt, flourishing African-American culture in the segregated South, outsiders changing world culture in the midst of hide-bound conservatism.

And yet, the driving forces in our history are creativity and passion, and that’s why the shrinking city discussion doesn’t have to be about despair. It’s not an academic exercise. It’s about a passionate belief that we can reimagine a future for Memphis that captures national attention but captures the attention of the toughest audience of all – Memphians.

In the end, annexation wasn’t the answer it was purported to be. It propped up Memphis population for a time; however, since 2010, Memphis’ population had dropped from 646,889 to 621,056 in 2022 caused some people to finally wake up and consider what policies are needed in a shrinking city. After all, the impact of this decrease rippled outward as Shelby County lost population and so did the Memphis MSA, which lost population in 2022 for the first time.

Beginning this conversation, rather than making comments of desperation and despair, is crucial, and there’s no time like the present.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram where these blog posts are published along with occasional articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

In 2000 I published maps showing where the City’s infrastructure funds were spent — the CA printed it. To summarize — we widened all of the roads on the edge of the city to 7 lanes and extended sewers to allow middle class residents (White and Black) to flee the city. In the meantime, we invested nothing in the older neighborhoods. I believe that being the most sprawled city in the country may be just as tough a challenge to Memphis as being among the poorest. I am pleased with all the new units being built in Midtown and other core neighborhoods, but it’s not enough. Being in the corner of the state, adjoining Mississippi and Arkansas, make it even more challenging.

Thanks for this great article. The disaster that accompanies sprawl has been apparent for decades, but it is a process that is hard to contain without the cooperation and assistance of the State government (in our case 3 State governments). If we allow all the little towns to expand willy-nilly, then Memphis has to follow — like it or not. And so, the competition for residents results in the mess we find ourselves in today. The Memphis metro cannot be made walkable and cannot be served by a reasonable transit system. It will take us as long to get out as it took us to get into this situation. Smart City Memphis has pushed making small parts of the region walkable and transit servable — like downtown. That seems to me a reasonable approach, when a macro solution is only a fantasy.