The National Civil Rights Museum has announced yet another expansion and renovation and it is a good time to celebrate this vital national monument that almost wasn’t built and once faced a takeover by state government.

Before the official groundbreaking in 1987 took place, there was an intense political struggle to get local funding from Memphis and Shelby County Governments and to enter into a contract with state government that set out the role of each government and the oversight of the state architect.

Along with Paul Gurley, Memphis Mayor Dick Hackett’s right hand man, and attorneys D’Army Bailey and A.W. Willis, I was tapped on behalf of Shelby County Mayor Bill Morris to negotiate the contract with state government and to develop a political strategy so

Memphis City Council and Shelby County Board of Commissioners would each commit $2.2 million as matching funds to State of Tennessee’s $4.4 million.

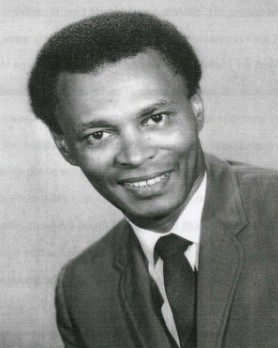

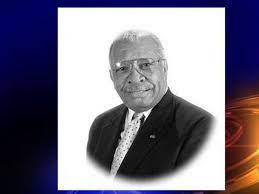

Civil rights lawyer and the first African American state legislator since Reconstruction, Mr. Willis was constant inspiration at times when the project appeared dead. There were often times when the prospects were bleakest that the museum would ever be built, he would say: “Tom, don’t worry so much. This museum is divinely ordained.” Sadly, he died in 1988 before the museum opened; however, he was right and because of it, the museum has been praised in national media and within the museum community.

Three people can rightly be called the

fathers of the National Civil Rights Center – Mr. Willis, Mr. Bailey, and Chuck Scruggs. Mr. Scruggs was the first African American general manager of WDIA and later “Mr. Chuck” on WKNO-TV and was first president of the

Museum Foundation. He died in 2013. D’Army Bailey, lawyer, judge, and first president of the museum board of directors, died in 2015.

There would be no museum without them. They bought the Lorraine Motel at foreclosure in 1982, conceived of a museum in it, and pushed the idea to the top of the local agenda.

The Era of Black Museums

That original $8.8 million government investment resulted in a 1991 grand opening and it was followed in 2002 by an $11 million expansion, and a $28 million expansion and renovation in 2014.

The best news about the recent announcement of another expansion and renovation is that the National Civil Rights Museum is not resting on its laurels. It is continuing to build on its reputation by expanding its exhibit space by 44% and updating exhibits to keep pace with technology and visitor expectations. This commitment to improvements has been especially crucial in light of the growing competition in an era that could rightly be called the era of African American museums and monuments.

Prior to the mid-20th century, the major repositories of African American art and artifacts were historically black universities and libraries, such as Hampton University, Howard University, Spelman College, and Fisk University.

The major burst in the development of African American museums began about four decades ago and has picked up momentum in the 1990s. Some of the new museums have been little more than vanity projects by individuals in a city, and others have been substantial projects funded by government. It is a reflection of the competitive times that several of them closed quietly only a few years after opening.

Why Museums Matter

Trends are clear and unmistakable. Arts, cultural, and historical institutions continue to divide into two groups – the fewer large museums that appeal to markets on a national, and even international, scale, and the more numerous small institutions targeting niche markets. The institutions caught in the middle often find the years cruel and unforgiving.

That’s why the real benchmark of success for the National Civil Rights Museum has been its success in elevating and strengthening its position as a museum of national importance and international scope. That then is the purpose of this new investment – to prove the museum should continue as a member of first-tier museums.

The essential functions of museums today can be summed up in three ways:

1) They are sources of entertainment, enrichment, and fulfillment.

2) They are vehicles for the preservation and transmission of culture, history, and values.

3) They are the sources of benefits at the personal, community, and national levels – openness to new ideas and creativity and broader personal competencies; social and economic benefits such as promoting livability, economic activity, and pride, and cultural diversity and pluralism at the national level.

A Unique Place

In considering a museum’s future, a key strategic question involves the core decision on how to increase participation. Generally, this presents three options – broadening, deepening, or diversifying it. In broadening it, the Museum captures a larger share of the existing market. In deepening it, the Museum intensifies the level of involvement by current visitors and supporters. In diversifying it, the Museum carves out new markets of people who are not typical visitors and supporters.

In other words, the fundamental challenge for the National Civil Rights Museum is to develop its position in a changing world increasingly more competitive and complex. The proliferation of African American museums can create consumer perceptions that every city has one and they are just “more of the same.”

That’s where Memphis’ competitive edge comes in. It is a lesson in how a city can transform the greatest tragedy in its history into a vehicle for historical accuracy, understanding, and purpose. No other city can attest to building its museum on what is sacred ground.

The Principle Realities

As the museum moves ahead, there are realities affecting every cultural institution in the U.S.:

Principle #1

Consumers are being pulled in a multitude of directions by convenient opportunities for entertainment that are increasing exponentially. More and more, people want what they want when they want it and where they are. Arts, cultural, and historical institutions are normally place-specific, and because of it, they must find ways to compete with entertainment that can be streamed, podcast, and DVD’ed. New ways are needed to connect with people where they are and to tap into a growing interest in being participants, rather than mere observers.

Principle #2

Every museum is a small island in a sea of cultural bounty. It won’t stake out its place by having a range of average activities, but by identifying a distinctive niche and producing “peak experiences” that differentiate it as the best at what it does.

Principle #3

Cultural and historical enterprises of all kinds are seeing the ground shift underneath them. There is the need for reinvention because audiences seem to be declining across the board for many traditional cultural anchors. The winners in this environment are those who fight commercialization that tends toward generic, derivative products. Authenticity and intimacy are ways to stake out distinctive territory.

Principle #4

Walker Percy said the problem with cultural institutions like museums is that we must wrest meaning from experiences that inevitably come to us prepackaged and disconnected from our own assumptions and expectations. Ways that connect more viscerally and more personally with citizens and visitors build a binding narrative for the National Civil Rights Museum, jolt the imagination, and raise expectations.

Principle #5

In the U.S. about 44 percent of whites, 28 percent of African-Americans and Haitian and 23 percent of Hispanics attended an arts/culture event or institution in the past 12 months. Education and income are the strongest indicators of cultural support. More college graduates – 64 percent – attend than high school graduates – 25 percent – and the higher the earnings, the greater the attendance at cultural events. While these groups are lucrative target markets, museums must make extra efforts to be accessible and meaningful to all citizens.

Principle #6

Special events are proven ways to animate and punctuate the life of a museum. These kinds of events offer unexpected surprises and speak to the values of the community and to the symbolic importance of events as rituals of hope and meaning for the museum. The National Civil Rights Museum has excelled in this respect with its important symposia and public events, and the recent groundbreaking for nearby Founders Park, a $9.6 million new park, will provide a new canvas for its work.

Looking Back

As a result, these are challenging days for museums of all kinds and the National Civil Rights Museum is no exception. In the past 32 years, it has established a strong foothold in the marketplace, born of its distinctive position as a sacred site in American history, positive reviews by national media, the lack of reliance on government funding, and the willingness of its board to make tough decisions with a strong business mindset.

These have served the museum well in the past and form a solid foundation as its leadership charts a course for the future in which the National Civil Rights Museum competes on a national stage to strengthen its position as one of the leading heritage museums in the country.

The announcement about the improvements to the National Civil Rights Museum takes me back to 1986 when the betting was that a civil rights museum in Memphis would never be

built. It was caught in the snare of racial politics in Memphis, and if it were not for Ned McWherter, the son of a share cropper who rose to become the always savvy and powerful Speaker of the Tennessee House of Representatives, it might never have happened.

With an eye on the governor’s office and an appreciation for the impact that the African-American vote in Shelby County could have on that race, Mr. McWherter came out in support of a civil rights museum at the Lorraine Motel and essentially dropped the political hot potato into the laps of Mayor Hackett and Mayor Morris, who did not have the votes for funding from their legislative bodies.

Funding Approval

Proving that timing is everything, Mr. McWherter’s race for governor changed everything. He promised $4.4 million in state funding, but it was contingent on an equal amount from Memphis and Shelby County governments. Strong opposition to local funding was immediate and stalled as city and county government leaders fought over which government should act first on the funding request.

In the face of stern pressure from opponents and supporters, Mayor Morris broke the logjam with some clever political theater. He announced that he would submit a funding request for $2.2 million to the Shelby County Board of Commissioners but he said it was contingent on about dozen rigorous conditions.

Opponents were satisfied because they presumed the museum’s sponsors would never be able to meet the conditions, which included a Smithsonian Institution-designed facility and no local government money for operations. What Mayor Morris knew was that all of the conditions had already been met. In short order, funding by city and county government was approved, and in 1987, the groundbreaking was held not too long after Mr. McWherter was sworn in as governor.

Divine Intervention

Designed by former exhibitions director at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History Ben Lawless, the National Civil Rights Museum opened September 28, 1991, but its construction was not without struggles. The site was firebombed, there were controversies about bids, it sold bricks from the hotel to raise money, and a laser beam tracking the trajectory of the bullet that killed Dr. King was deem in poor taste and eliminated.

In a marketplace with more than two dozen African-American and civil rights museums built since 1988, some costing more than $100 million, the National Civil Rights Museum is noteworthy for its steady growth and management while some other major museums have foundered and Virginia’s proposed U.S. National Slavery Museum raised money for years but was finally abandoned.

Through controversy, opposition, conflict, and competition, the National Civil Rights Museum prevails and continues to improve. It’s little wonder that Associated Press once wrote called it “the best and most recent scholarship on civil rights today.” There is nothing in any museum anywhere as moving and emotional as standing outside Dr. King’s hotel room and considering the awful moment that Memphis and the country’s history were forever changed.

As for Governor McWherter, he died in 2011 on April 4. It was the 43rd anniversary of the day that Dr. King was murdered.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.