Above Photo: Rabbi James Wax on Upstanders Mural in downtown Memphis

**

It’s hard to think of a more appropriate time, with next week’s anniversary of the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., when we should be recommitting ourselves to the cause of social justice.

It is certainly needed now more than ever. It is under attack as “woke” by those who rail against policies aimed at equality and equity in our country. It is a sad commentary on the times that extremist governors are now attacking social justice as some alien concept that justifies the banning of books, the dumbing down of education, the discrimination of other Americans based on race or gender identity, and seeing CRT around every corner.

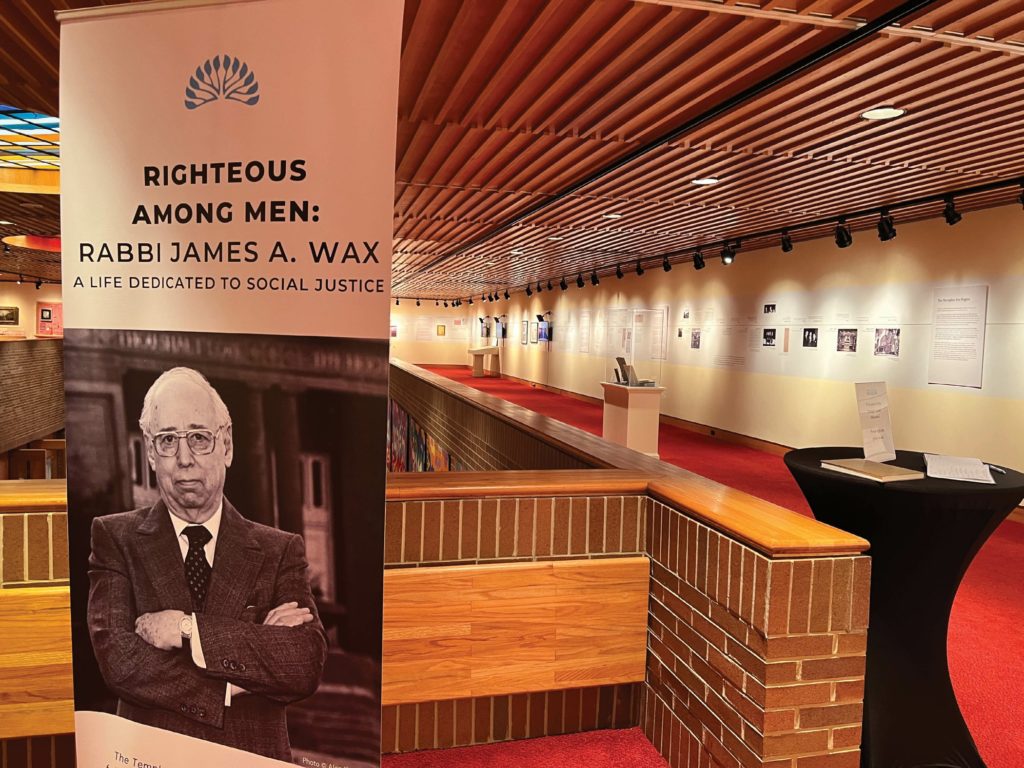

It there has ever been a time for a social justice movement, it is now. An exhibit on the life of Rabbi James Wax at Temple Israel Museum is a timely reminder of that fact.

It there has ever been a time for a social justice movement, it is now. An exhibit on the life of Rabbi James Wax at Temple Israel Museum is a timely reminder of that fact.

We of course have the powerful national example in the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. but we also have the courageous local example in the life of the late Temple Israel Rabbi Wax.

Appealing to Memphis’ Conscience

In his career in Memphis, he led the movement to create a mental health commission, to push back on a mayor fighting the reform of City of Memphis government, to lead the desegregation of public facilities, and to call out the governor for politicizing the hiring at Tennessee’s mental hospital.

Most of all, he is known for his role in the sanitation strike where he hoped to mediate a solution based on his belief that reasonable people could always find a reasonable solution. He had not counted on the racism of Mayor Henry Loeb who rejected every option for a solution to the strike. Rabbi Wax convened meetings of all sides and encouraged common ground but it was no use when confronted by a recalcitrant mayor unwilling to give an inch.

By the time he became a leader searching for answers, he had been elected as the first rabbi to head the Memphis Ministers Association. There, he made an early stand against bigotry. He urged the group to issue a statement, An Appeal To Conscience, which was printed in both daily newspapers. It called on Memphians to observe Race Relations Sunday on February 11, 1968. “We ask for an end to racial discrimination in all areas of human experience,” it said. He was furious that Mayor Loeb would not sign a proclamation for Race Relations Sunday.

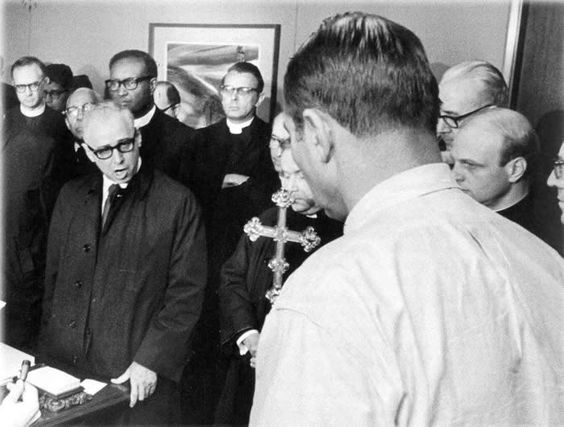

That frustration grew as mediations went nowhere and it boiled over on April 4, 1968, when Dr. King was murdered. On April 5, he led a march of 250 ministers down Poplar Avenue from St. Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral to Mayor Loeb’s office. There, admittedly emotional, he rebuked Mr. Loeb for not ending the strike and leading to Dr. King’s death.

With righteous anger in his voice, he said:

“We come here this morning with a great deal of sadness in our hearts but also with a great deal of anger, sir. What has happened in our city is the result of injustice and oppression and the lack of human decency and concern for human beings…shall be ruled with justice and justice for all. I realize we live in a society of law and order. We must have laws, but I would remind you most respectfully, sir, there are laws that are greater than the laws of Memphis and of Tennessee. The laws of God, and the laws of God are not subject to any Gallup poll. Speak out in favor of human dignity for every person. Let us not hide behind legal technicalities. Let us not wrap ourselves up in slogans. Let us do the will of God for the good of the city.”

“We come here this morning with a great deal of sadness in our hearts but also with a great deal of anger, sir. What has happened in our city is the result of injustice and oppression and the lack of human decency and concern for human beings…shall be ruled with justice and justice for all. I realize we live in a society of law and order. We must have laws, but I would remind you most respectfully, sir, there are laws that are greater than the laws of Memphis and of Tennessee. The laws of God, and the laws of God are not subject to any Gallup poll. Speak out in favor of human dignity for every person. Let us not hide behind legal technicalities. Let us not wrap ourselves up in slogans. Let us do the will of God for the good of the city.”

(Listen to Rabbi Wax’s statement to Mr. Loeb here,)

Rev. Lawson’s Reflections

His reproach was broadcast on local and national television news programs and reprinted in local and national newspapers and magazines. Some White ministers were fired or moved out of Memphis but Rabbi Wax faced no such threat from Temple Israel, which had a long tradition of speaking out against prejudice and oppression.

Reflecting on the days of the sanitation workers strike, Rev. James Lawson, then pastor of Centenary Methodist Church and vice-president of the Memphis Ministers Association as well as strike chairman and strategist for the strike, said recently:

“I had studied a lot about the Hebrew Bible since before I was 10 years of age. I knew James Wax as the part of the community talking to Mayor Loeb and to white businessmen vocal about ending the strike. James Wax was very active in that process, pushing to change Memphis. I always spoke about nonviolent resistance and lessons from the Hebrew Bible that I discussed with him.

“My connections with James Wax were more my connections to prophetic religions and the high form of religion that it represented to me. We treated each other as first cousins of the Hebrew prophets. Social justice was a theme that came straight from the Hebrew Bible into the Scriptures. One of our models in nonviolent resistance was justice, liberty and equality and the beloved community. It is very much a part of it all and it’s what joined Rabbi Wax and me. For me, my connection with Rabbi Wax was as a fellow prophet out of the Moses tradition, the Micah tradition.”

Finding Life’s Calling

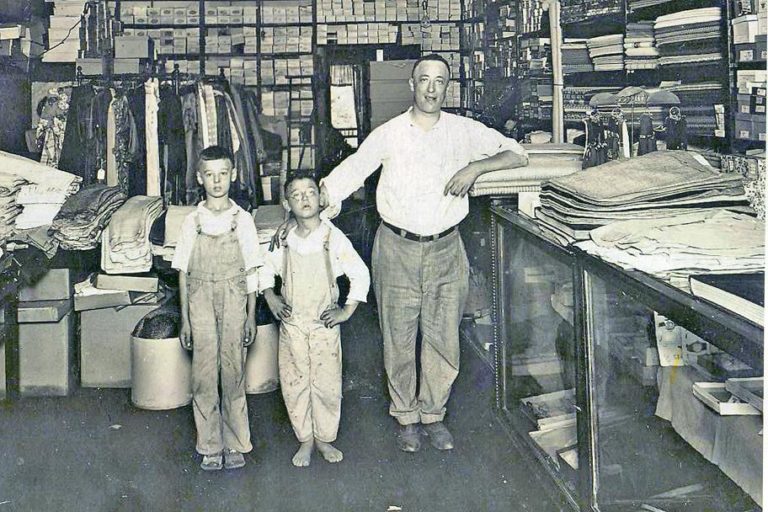

James Wax, left, with brother and father

James Wax, left, with brother and father

It was an improbable journey that took Jimmy Wax from the hard scrabble mining town of Herculaneum, Missouri, to become a staunch lifetime advocate and defender of social justice.

He never lost sight of his life’s mission – to speak for those who had no voice, to speak out against injustice and bigotry, and to inspire his city and his congregation to risk everything in pursuit of decency, equality, and understanding.

His commitment to social justice was built on his commitment to America, the country where his parents moved to escape the anti-Semitic pogroms in the Pale of Russia in 1910. From his teenage years as a prize-winning orator and debater to the end of their lives, his parents were deeply patriotic about their new country and endowed him with a love of the United States and a desire for it to fulfill its full promise for every person.

Even as a teenager, he was frequently asked to speak about patriotism and our common humanity. He was invited to speak to civic groups and at the Methodist Church and even served as the keynote speaker at the groundbreaking of an African American Baptist Church.

In Herculaneum, Missouri, his family was only Jewish one in town. As a result, he had no Jewish friend, no town synagogue, no Bar Mitzvah, and he couldn’t speak Hebrew. But Herculaneum was the seedbed for his lifelong concern for the “little guy,” which was kindled even more when he attended a service in St. Louis where Rabbi Ferdinand Isserman challenged Temple youth to fight injustice. After being accepted at Hebrew Union College, he learned that social justice was the heart of Judaism, and from his earliest sermons, he focused on this religious imperative.

The Voice for the Voiceless

He moved to Memphis in 1946 to accept the assistant rabbi post at Temple Israel and in 1954, he was installed as senior rabbi.

At his installation, his predecessor, Rabbi Harry Ettelson said: “James Wax would not speak as Temple Israel wants him to speak. He must speak as God wants him to speak.” In his reply, Rabbi Wax staked out his claim to a social justice ministry: “Social justice, the genuine concern for one’s fellow man, is the cornerstone upon which the world is built. I shall in the course of time say things with which you shall not agree. Mine is the duty not to listen to man, but to listen to God.”

After moving to Memphis, he quickly became active in mental health and desegregation. He was the first president of the local mental health association and he was the first Jewish president of the Memphis Ministers Association. He was also a member of various civic and charitable groups and received numerous awards for his contributions to Memphis.

From the beginning, Wax’s strong stand on equal rights for African Americans set him apart in a culture where that was far from the norm. In 1952, Wax received an honorary divinity degree from Tusculum College, a Presbyterian college which was the first in Tennessee to admit African Americans.

In a 1953 speech reported in The Commercial Appeal, Rabbi Wax told the Brotherhood of Temple B’nai Israel: Every human being, regardless of his nationality, religion or race, was created in God’s image. Every human personality bears the imprint of divinity. Whatever we do that harms another person, that dwarfs his divinity. Whatever we do that harms another person that dwarfs his being, that denies him the opportunity to achieve his utmost potentialities is a sin. Prejudice, like robbery, is a sin. Hatred, like adultery, is a sin. No person is either a good Christian or a good Jew who is guilty of the sin of bigotry and intolerance. Judaism and Christianity, the dominant religions of the Western World, enjoin us to love God and to love our fellow man.”

Truth To Power

By 1956, his leadership led the Tri-State Defender to honor him for “his consistent effort to bring about peace and harmony between the races.” Two months later, he withdrew from a Religious Emphasis Week speaking engagement at University of Mississippi in protest against the college’s cancellation of an invitation to a White minister who supported the NAACP and opposed segregation.

But his fiery comments to Mayor Loeb were not the last time he spoke truth to power.

Seven years later, Rabbi Wax would be in the news again when he stood up to Governor Ray Blanton in 1975 when he attempted to politicize hiring at the state mental hospital. For Rabbi Wax, mental health was a core part of social justice.

In 1950, he was elected president of the newly formed Memphis-Shelby County Mental Hygiene and later was named by Governor Rank Clement to Tennessee Mental Health Commission where he served for 25 years. In that role, he stood up to Governor Ray Blanton in 1975 when he attempted to politicize the state mental hospital. The disagreement with the governor received widespread media coverage and resulted in editorial praise for his actions.

Rabbi Wax gave his last sermon as senior rabbi on March 11, 1978, after 32 years associated with Temple Israel and after leading the effort to build a new synagogue. Local media published glowing articles about his impact on the history of Memphis. He continued to write columns about social justice for local media, taught a popular course at Memphis Theological Seminary, and continued to serve as rabbi to the Jewish communities in small Mid South towns.

He died October 17, 1989, after suffering an aneurysm while conducting Yom Kippur services in Helena, Arkansas. His last words were about social justice: the moral right of every person to have decent, affordable health care.

The April 5, 1968, Sermon

He is remembered for one of his briefest and most powerful sermons, given only a few hours after leading the ministers’ delegation to meet with Loeb:

Speaking this morning to the Mayor of our city, I said to him that I spoke with mixed emotions, of sadness and of anger, of deep and righteous resentment, and the view which I expressed is the view of the clergy of the city of Memphis. I know there are people in our city tonight who are not sad at what happened last night. I know there are some people in our city who might even be glad. I remember a few weeks ago at the Rotary Club when the television newscaster made his five minute report announcing that Dr. Martin Luther King was coming to Memphis there were some who sneered, and some who mocked the announcement. But I wonder who those people are contrasted with Martin Luther King. Who is this man, Martin Luther King that the President of the United States should proclaim a national day of prayer? Whose death is mourned in the capitals of the world? Whose death is deeply regretted by responsible people, decent people, wherever they may live? Who is this man whose name was sneered and mocked by some of our so-called civic civic leaders? I shall answer very simply and briefly, Martin Luther King was a prophet, a prophet like Amos and Isaiah and Jeremiah, a man who walked in the footsteps of Moses. And (if I were speaking in a Christian congregation) walked in the footsteps of Jesus.

What did Martin Luther King do? Martin Luther King helped to bring freedom to the oppressed people yet in this nation. He fought to break the chains that have oppressed people, he sought to give men dignity, he sought to make this a better world in which to live. Oh, how the cynics sneered when they gave him the Nobel Peace Prize. they said, “What did he do to deserve it?” How little can people be? Here was a man in the tradition, the grandest traditions of Judaism and Christianity, bringing freedom to people. And we white hypocrites that speak about freedom for all people know full well that not many miles from here Negroes could not vote. In this very city, called a place of good abode, because their skin what black, they had to sit in the back of the streetcar. They were not even given the dignity of their name.

Martin Luther King was one of the greatest men of this century because he personified the greatest teachings in Judaism and in Christianity, and he did it without violence. He sought to appeal to the heart and the conscience of man.

When I memorialized or tried to memorialize the late President John F. Kennedy, standing in this place, I said, “You Judge a man not merely by the friends he has, but by his enemies.” Who are the enemies of Martin Luther King? Segregationists! A segregationist is a bigot. A segregationist violates the laws of the Torah. A segregationist desecrates Judaism. These are the people who dislike Martin Luther King.

**

The exhibit, Righteous Among Men: Rabbi James A. Wax, A Life Dedicated to Social Justice, is at the Temple Israel Museum, 1376 E. Massey Road. The exhibit was inspired by Susan Adler Thorp in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and who, with me, wrote the narrative and identified the exhibit artifacts. The exhibit was curated by Laura Gray McCann.

Exhibit Hours:

Tuesday-Thursday 10 AM-2 PM,

Sundays 10 AM-12 PM,

First Friday of the month before Shabbat services from 5-6 PM.

Listen to Torah to the People podcast interview of Susan Adler Thorp by Rabbi Jeff Dreifus about Rabbi Wax and the Temple Israel Museum exhibit.