I rise in defense of Sidney Shlenker.

That may be the first time that has been written about him in 30 years.

His name has become the ultimate barb in a comment on a newspaper article about a sketchy downtown real estate developer or leveling the worst possible insult at someone whose project a reader opposes. There are times when Mr. Shlenker sounds like a villain rivaling Keyser Soze, Michael Corleone, or Kylo Ren.

Many of the facts about his involvement with what he called the Great American Pyramid have faded in time, replaced by urban myths and stories like something emerging from the Telephone Game.

In a sentence, Mr. Shlenker deserves better…or at the least a fuller understanding of what happened to kill the plans for an attraction to complement the arena at The Pyramid.

The Cast of Characters

It begins at the beginning. It’s not like he did not have credentials.

Mr. Shlenker owned the Denver Nuggets of the National Basketball League and was co-owner of Pace Management Companies, one of the largest production event companies in the country with 10 productions of Broadway shows, 300 concerts, 90 motorcycle races, and assorted arena events.

He previously had been CEO/President of Houston Astrodomain Corp, the Astrodome’s parent organization and in that position, he was head of Houston Astros professional baseball team and later became minority owner of the Houston Rockets basketball team. He also famously arranged the tennis match between Bobby Riggs and Billy Jean King in the “Battle of the Sexes.”

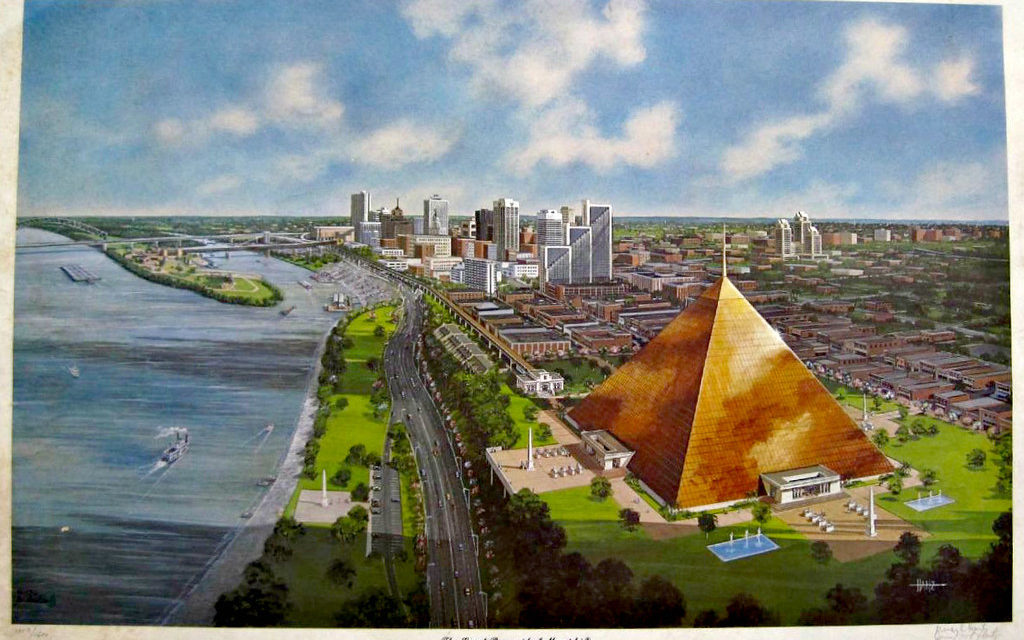

Meanwhile, back here, Jon Brent Hartz had drawn a rendering of a striking bronze glass pyramid. His artist father, Mark Hartz, had been pitching the idea of a great Pyramid in Memphis for about 30 years, but it was his son’s rendering that captured the interest of John Tigrett, entrepreneur, inventor, and wheeler dealer in Memphis and London.

Mr. Tigrett, who, along with his wife, Pat Kerr Tigrett, were prominent civic actors and politically connected. Supported by her cheerleading, he became the driving force creating a campaign to build a pyramid on the riverfront, preferably where South Bluffs are today. Fortunately, developer Henry Turley convinced the powers-that-be that the South Bluffs would be a waste of a dramatic location better suited for residential development.

The Lure of a Major Attraction

With Mr. Tigrett calling on his friends and calling in favors, the idea picked up steam and prominent attorney Lewis Donelson got on board. In selling the idea to the city and county mayors, Mr. Tigrett assured that the landmark could be built for $39 million as a “state-of-the-art” arena, including the price of the balloons for the ground-breaking. (The hyperbole about the quality of the building was made obvious when a real state-of-the-art arena, the $230 million FedExForum, opened in 2004.)

The Pyramid would ultimately cost $62 million – funded by Memphis, Shelby County, and University of Memphis, increasing from the unrealistic price of $39 million after several scope changes to the design, notably that a glass exterior was impractical.

The sizzle on the steak, as it was described by Mayor Morris, was the opportunity to add a major attraction – or two – to the skirts of the building which were not needed by the arena. The attraction was to include a Hard Rock Café, part of the international chain of iconic music-themed restaurants run by Mr. Tigrett’s son Isaac.

Design for the arena was detailed but the so-called “attraction space” was more spatial than defined, fluid and undetermined except for the idea that it should be a tribute to Memphis’ music heritage and Egyptian name.

The Foreboding Groundbreaking

So, Mr. Tigrett and his allies convinced city and county government officials to support and fund construction of the pyramidal arena, but left to define was the kind and scope of the attraction. It needed someone with experience in big projects, someone who could oversee imaginative attraction design, someone who was thought to have deep pockets or friends with deep pockets, and someone who could “sell” the project to this community – “our own P.T. Barnum,” one project supporter said.

Mr. Shlenker was that in spades.

Mr. Tigrett learned about him from a mutual friend who said he was perfect for the Memphis project. Based on his friend’s opinion, Mr. Tigrett contacted Mr. Shlenker and recruited him to Memphis.

As Mayor Morris said, “Sidney Shlenker could sell ice to the Eskimos,” and in a trip to Denver by a Memphis delegation to meet him during a Denver Nuggets game, he was charming, convincing, and seemed the perfect fit for the job.

He moved to Memphis in 1989 and when asked about him, Mr. Tigrett said, “I vouch for him.” The September 16 groundbreaking for The Pyramid, called The Big Dig, was held September 16 and it was emblematic and symbolic of what was to come.

Casting A Spell Over Memphis

It was emblematic because it was unnecessarily extravagant after being choreographed by Mr. Tigrett’s wife, Pat Kerr Tigrett. The event cost almost $500,000 at a time when the company – the Pyramid Cos. – had no money. Living beyond its means became a way of life for the newly formed company as partners scrambled for the millions of dollars it would need in operations, but more to the point, the tens of millions of dollars it would need to build out an attraction.

It was symbolic because the first groundbreaking event was rained out, a foreshadowing of future problems that suggested the project was jinxed – the death of a workman; pull-out design flaws like seats that were too narrow, stairs to seats that were too steep and inadequately lighted, causing a pregnant woman to fall, VIP suites that were anything but VIP; inadequate ADA designs; the warring partners; the overflowing toilets on opening night; and the horrendous sound quality.

The initial concept for the privately-funded attractions included shortwave radio station at the building’s apex broadcasting Memphis music, an observation deck reached by an inclinator up the side of the building, a Hard Rock Café, and a music museum. However, no plans were fully formed and most of all, none had specific costs and designs.

It was not long that Mr. Shlenker charmed Memphis and cast a spell with his extravagant hype about what the Pyramid would become and how it would attract millions to the city for the once-in-a-lifetime experience it offered. Mr. Shlenker was seen as a magician to the point that Memphis Mayor Dick Hackett convinced him to add Mud Island to his responsibilities and the promoter proposed a $110 million music/Egypt theme park called Rakapolis there.

His management and operations of Mud Island were in a word, disastrous. The outstanding children’s playground was destroyed and the placid Gulf of Mexico at the end of the scale model of the Mississippi River became Bud Boogie Beach, a swimming pool and beach. Unfortunately, the Gulf of Mexico was designed for wading, not for swimming, and health issues arose. But equally important, taking over Mud Island spread Mr. Shlenker’s interest in the Pyramid too thin as he now looked for money to pay for his vision for it and Mud Island.

The Collapsing Partnership

Today, it’s easy to look back at The Pyramid and see trouble signs that were largely kept from the news media and the public. Mr. Shlenker’s strong public persona and wide acceptance were evidenced in his being named “Memphian of the Year” by Memphis magazine in 1989. At the time, he had an open door to both city and county mayors’ offices and strong relationships with City County and County Commissioners.

Two years later, he was mocked on the same magazine’s cover as Humpty Dumpty, and he moved away in disgrace, furious that Memphis politicians had abandoned him just as he thought he finally had financing for the attractions.

Meanwhile, with Mr. Shlenker as the ever-present face of the Pyramid Companies, Mr. Tigrett largely escaped blame, and while Mr. Shlenker was vilified and moved out of the city, Mr. Tigrett was unbruised and unbattered as Mr. Shlenker became the scapegoat as if Mr. Tigrett had never been involved in the project.

The two years of their partnership were a wild ride for everyone connected with the partners. As their personal relationship disintegrated and they went to war in the final months of their company, government officials divided into “Shlenker people” and “Tigrett people.”

Or more precisely, elected officials were divided. Most staff members preferred Mr. Shlenker because Mr. Tigrett tended to be dismissive of them. Even in the midst of the ugliest chapter of the fallout between the two men, Mr. Shlenker was unfailingly agreeable while Mr. Tigrett could be abrasive.

Several of us at First Tennesse met with Shlenker regarding possible financing and immediately determined that traditional bank financing was not viable. It was quite obvious to us right away that there was no financial substance to the business plan and if the Pyramid was going to happen, the financial backing was going to have to come from governmental sources. I recall the picture in this article – it was taken in front of his home on Walnut Grove at White Station, directly across the street from Jack Belz’ home.