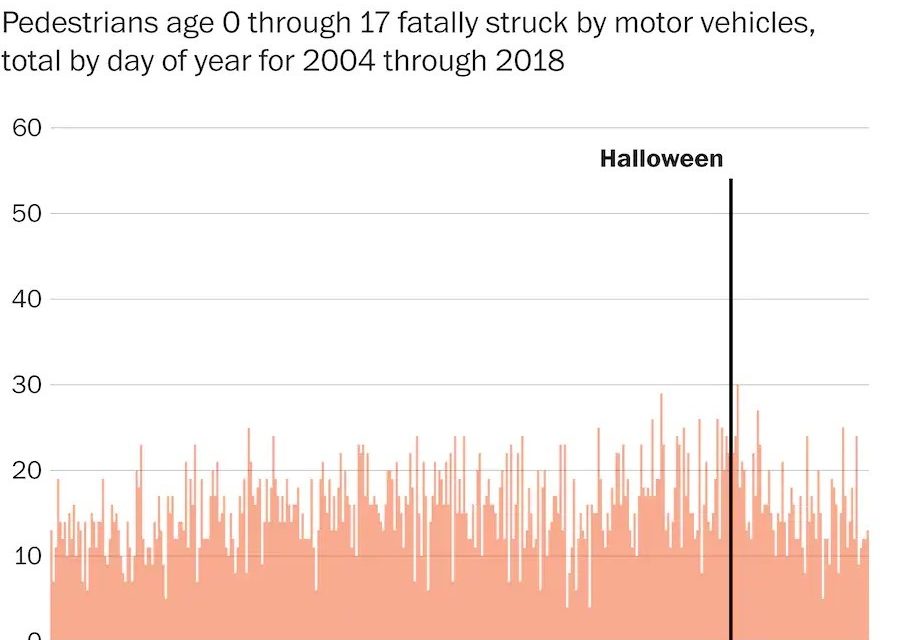

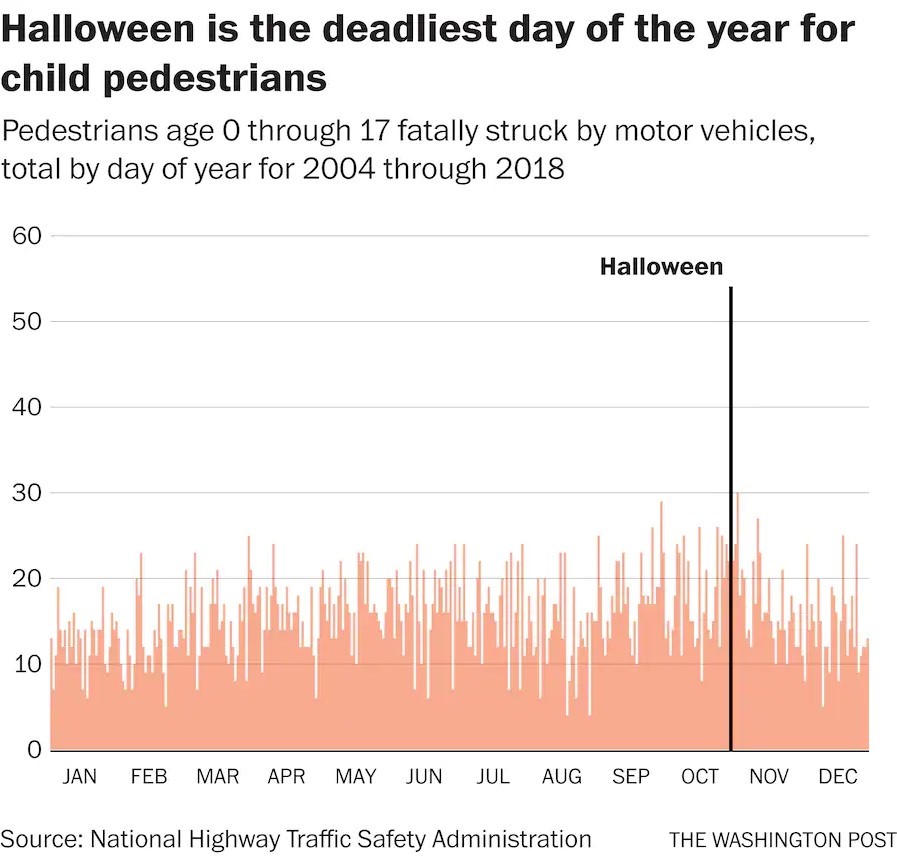

As Halloween approaches, so too do mostly baseless infographics that encourage parents to check their kids’ Halloween candy for razor blades or marijuana (yes, some people actually believe that strangers want to swap $1 of Sour Patch Kids for comparatively expensive THC gummies just to get trick-or-treaters high). But the real danger to kids on Halloween is cars. Kids are more likely to be killed by cars on Halloween than any other day of the year.

The American Exceptionalist can’t avoid the United States’ astronomical death rate from road accidents–it’s higher than that of Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, and the European Union. When considering the death rate per-miles-driven, the U.S. still has a higher death rate than much of Europe. Even with the United States’ extremely high car accident death rate, Memphis suffers from problems associated with dangerous roads at a rate significantly higher than the national average.

As I wrote in August, Memphis had the highest pedestrian fatality rate in the country in 2018. A 2022 report from Smart Growth America singles out Union Avenue as an example of what a dangerous-for-non-drivers street looks like–and it isn’t at all unique. Any trip through Memphis will feature plenty of streets that look like Union. They’re everywhere.

Memphis streets favor the car by design. My college advertised Memphis as a city with an extensive network of bike lanes, and they’re right… sort of. Memphis certainly has bike lanes. But a six-inch strip of white paint that appears and disappears abruptly won’t protect a cyclist from a 5,000 pound pick up truck going 40 miles per hour, which is the legal speed limit on many streets in Memphis. 264 pedestrians were killed in the Memphis area from 2016-2020. When adjusted for population (average pedestrian deaths/100k people per year), that makes Memphis the third most dangerous metro in the country for non-drivers.

Part of the problem has to do with culture. It’s culturally sexy in the United States to own an F-150 or a high performance sports car. The same can’t be said for taking public transit or owning an e-bike. That cars are cool is culturally enforced. The President of the United States is a self-proclaimed “car guy” (just look at the title of this article: ‘Biden hops into Corvette, declares Detroit ‘back’ at EV-focused auto show’). Post-WWII engineers redesigned North America around the freeway/highway system. Most state DOTs focus on moving cars as quickly and efficiently as possible at the expense of people who aren’t in cars. The Georgia Department of Transportation is investing in the widening of freeways on the scientifically disproven notion that widening freeways will reduce carbon emissions and speed up traffic. In Oregon, a state known for its progressiveness on climate issues, two out of the three gubernatorial candidates are running on the same false notion.

Even if every driver switched to an EV, most negative impacts of cars will stick around, such as urban sprawl, destruction of ecosystems, and deaths of non-drivers and drivers. Carbon emissions would still exist from the building sector, and many materials used for EV batteries are non-renewable. As Charles Marohn points out in his Strong Towns article, ‘Here’s Why We Respond in Force to One Amtrak Crash While Ignoring Thousands of Daily Car Crashes,’ “Part of why this problem has been so difficult to address is that it requires a messy, complex, bottom-up, and deeply personal response. Those are hard to do, especially if your underlying operating system—your fundamental DNA—is top down.” Many people prefer to accept big statements and comforting visions from leaders rather than the hard work of meaningful change. Paris, a city that was not too long ago unfriendly to cyclists, plans to become a 100% cycling city by 2026, and plans to ban most cars by 2024. Cities don’t magically become more sustainable and livable. It takes decisive leadership.

The other part of the problem has to do with convenience–it is really convenient to own a car in this country, especially in auto-dependent metros like Memphis. It’s impossible to say that car accidents are the result of individual drivers making bad decisions when urban infrastructure doesn’t consider the safety of non-drivers; if a place is built for cars and traffic, cars and traffic are exactly what you’ll get.

It makes sense that non-drivers aren’t safe in a place that isn’t built for them. I saw a kid walking home from school in Barlett, backpack strapped over their shoulder, on the highway, towards oncoming traffic, because there was no sidewalk. There was no other choice. It’s simply safer (for yourself), quicker, and easier to drive a car in Memphis than it is to consider alternative forms of transportation. (…all those parking lots right by Beale Street, including the 960 space “mobility center,” A.K.A. a glorified parking garage, currently under construction across the street from Beale’s entrance, seem to invite drunk driving. But that’s a conversation for another time….)

There are lots of ways to potentially improve safety on Memphis streets. The one that I think would be the most beneficial in terms of safety, health, and financial resilience is an all-in commitment to build a robust network of protected bike lanes.

Let me explain: A 2019 study that spans 13 years of data from 12 U.S. cities found that cities with protected bike lanes have safer roads not just for cyclists, but all road users. Yes, even drivers. In fact, cities with protected, separated bike lanes have 44% fewer deaths and 50% fewer serious injuries than the average city. The researchers, from the University of Colorado Denver and the University of New Mexico, analyzed over 17,000 fatalities and 77,000 severe injuries in cities such as Denver, Portland, Dallas, Seattle, San Francisco, Kansas City, and Chicago, all cities that had an increase in cycling and cycling infrastructure from 2000-2012. It is important to note that these cities have varying rates of gentrification, which can affect the results because of disparities in safety associated with gentrification (higher rates of safety improvements in gentrified areas exemplify equity issues). The researchers expected to find that more cyclists would slow down driving speeds, but what they actually found was that cities that added more cycling infrastructure, particularly physical barriers that separate bike lanes from cars, lowered fatalities by a significant margin.

In Portland, the population of bike commuters increased from 1.2% to 7% between 1990 and 2015. Fatality rates dropped by three quarters, even as the population increased, to 4.5 fatalities per 100,000 residents. This is a comparable rate to the countries that boast the lowest crash rates in the world, such as the Netherlands, which reports a rate of 3.4 fatalities per 100,000 residents. The Netherlands has a bicyclist mode share of 30%, so their low fatality rate is no coincidence. Fatal crash rates fell by 61% in Seattle, 49% in San Francisco, 40% in Denver, and 38% in Chicago over the same period as they built more protected and separated bike infrastructure. The researchers discovered that these sorts of bike facilities slow cars down, and even if a driver collides with another driver, it’s less likely to be fatal. Protected, separated bike lanes are good news for drivers, cyclists, pedestrians, accessibility vehicle users, and trick-or-treaters.

Just as important as their findings on what improves safety are their findings on what decreases safety. The researchers found that painted bike lanes provide no safety improvement, and another review from the same researchers found that shared roadways (where a bike symbol is painted in the middle of the road) actually decrease safety. On shared roadways, Wesley Marshall, co-author of these studies and professor of engineering at the University of Colorado Denver, told Streetsblog that, “We found that they’re worse than nothing. You’re better off doing nothing. It gives people a false sense of security that’s a bike lane. It’s just a sign telling cyclists it might just be there.” There are some shared roadways in South Main, for example, that get a ton of car traffic. Theoretically, they are less safe for cyclists because of their designation as a shared roadway than they would be even as a normal road.

Additionally, the researchers found that not all protected bike lanes are equal. In Denver, for example, they noted that many protected bike lanes feature plastic bollards interspersed along the roadway, which allows cars to park in the bike lane, forcing cyclists to swerve into the street. I noticed this phenomenon in Memphis this morning, as several cars were parked in the protected bike lane on Dr. MLK Jr. Ave. There are some great sections of this bike lane, particularly closer to Downtown where planters physically separate the bike lane from the road. Now it’s just a matter of making that level of safety consistent.

The Mid-South has higher rates of disability and death from heart attack, stroke, cancer, kidney failure, and arthritis than anywhere else in the United States. Derek Thompson points out in his Atlantic article, ‘America is a Rich Death Trap,’ that the U.S. fares worse in life expectancy than other high-income countries. Some of the most immediate causes of our high death rate are guns, drugs, and cars. Yes, largely because of road accidents, but also because auto-centric infrastructure promotes a sedentary lifestyle. It also helps sustain fast food chains that require drive-thrus. An increase in bike infrastructure could lead to a long overdue disinvestment in the car, replacing desolate infrastructure with activated urban spaces, and afford people more opportunities to spend time outside with fun aerobic activity.

And no, e-bikes aren’t cheating. In fact, this study found that people who ride e-bikes get as much or more exercise than people who ride regular bikes because they ride farther and more often, probably because it becomes a less daunting activity. Plus, the pedal assist on e-bikes pretty much does away with the concern that replacing driving with biking would turn errands into a strenuous activity. From a climate perspective, biking is about as low-emission as vehicles get, and is a great way to improve air quality. Basically, biking makes cities more livable for everyone.

A study by (ironically) AAA found that the auto industry really wants your money–the average annual cost to own and operate a new car is almost $11,000 in 2022. This is almost a $1,000 increase from 2021. That’s roughly 26% of the median annual income for the city of Memphis from 2016-2020. In Orange Mound, that percentage rises to 41%.

Many people say that e-bikes aren’t a worthwhile investment because they’re so expensive. But even the cost of the priciest city e-bike on the market pales in comparison to that of a car. In addition to all the social, environmental, and health and safety benefits to bikes, they could also be a valuable wealth-building tool by removing the annual financial burden of car ownership.

It is important to acknowledge that not everybody can bike. There are certainly accessibility issues when it comes to bike infrastructure. But bike lanes are great for all methods of rolling. Protected, separated bike lanes could be used by bikes and accessibility vehicles alike. The same can’t be said for an arterial road. And separated bike infrastructure would separate cars even further from sidewalks, making cities safer for pedestrians, too.

Equity, or lack thereof, is at the center of all of these issues. Many of Memphis’ majority-Black neighborhoods are food deserts. Meanwhile, there’s a Trader Joe’s in Germantown and a Fresh Market in Midtown. BIPOC Memphians suffer poverty at higher rates and have less access to health care than their white counterparts. The most filled out sections of bike lanes I have seen are in wealthier neighborhoods, like

Cooper-Young and other neighborhoods across Midtown and Downtown (even in these areas, the car still clearly comes first). Memphis has a long way to go when it comes to making the city safer for non-drivers. As Memphis improves its non-driving infrastructure, it is essential that it does so for all Memphians.

Owen Traw is a student at Rhodes College studying urban studies, philosophy, and Spanish. He grew up in Portland, OR, loves cities, and is interested urban policy and activism.