The last blog apost reported on how the Memphis region will spend more on higher gas prices than just nine other U.S. cities, the result of sprawl and poor public transit.

University of Memphis Professor Emeritus David Ciscel added valuable context in his comment to the post: “Sprawl has been a long-term issue for Memphis. Though most US cities suffer from sprawl, Memphis certainly has a strong racial/class background to its sprawl. In the 1970s, Germantown and Collierville were distance small towns, not integral parts of the metroplex like they are today. Racial integration is certainly a key factor in that change.

“The cost of driving to and from work, social engagements and shopping trips is large. Most people never add up how much it costs to operate their cars/SUVs, because there is little choice to driving an automobile. But there is even an additional cost: Lost TIme. Being behind the wheel is very unproductive for most people. If you are driving 50 miles per day, then you are probably losing an hour and half of work income or an hour and half of real leisure. That is not a small part of the costs of sprawl.”

Memphis is #9 among a ranking of the 52 largest region with an average miles driven per day rate of more than 50 days a day.

It is no coincidence that Memphis is a leading city for economic segregation, limiting opportunity, quality of life, and equity and producing a seemingly irretrievably divided community. It’s also no coincidence that the density inside Memphis was cut in half, driving up the cost of city public services and putting pressure on city budgets.

No one in Memphis knows more about the implications of sprawl than Dr. Ciscel. In fact, he’s been writing about it for more than two decades, including the seminal study on the impact of sprawl on the Memphis region around 2000.

Regrettably, policy makers failed by and large to give his research, data, and results more than lip service. Meanwhile, the sprawl brought Shelby County Government to the brink of bankruptcy and in Memphis, urban neighborhoods were forced to invest in the decline of their own neighborhoods as their tax dollars were spent on the fringe of the city rather than on attacking the disinvestment they could see out their front doors.

In light of my recent blog post, I revisited one of Dr. Ciscel’s reports on sprawl published by Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis:

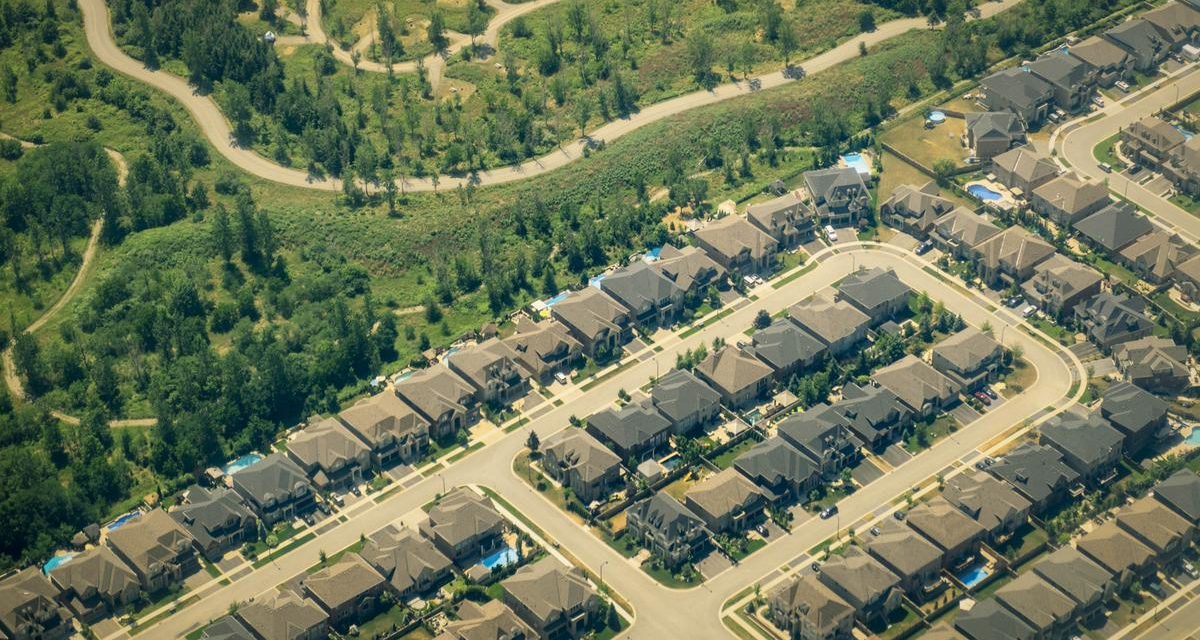

Urban sprawl is a term that has an immediate public policy connotation. The term implies the modern city is expanding in an irrational pattern—haphazardly in all geographic directions. Sprawl, the geographic spread of a city based on automobile commuting, has both positive and negative characteristics. After all, bringing the potential for suburban living to a larger portion of the population was one of the great social projects of the 20th century.

Researchers who are interested in the problems of urban sprawl raise two issues: (1) the social inequity and (2) the economic inefficiency of the large city. Most critiques of urban sprawl focus on the geographic unfairness in the delivery of services and jobs in the modern city. In addition, the urban elderly, young and poor suffer from living in the older, less maintained parts of the city. In many instances, it is the urban residents who finance, through their taxes, the infrastructure for the new suburban subdivisions. These questions of fairness are important, but urban sprawl also raises questions on economic efficiency in urban design.

I recently conducted a study to examine the structure and costs of urban sprawl in the Memphis metropolitan area. The results indicate that urban sprawl in Memphis has produced unintended side effects, including:

- Physical separation of the social classes;

- Abandonment of the old city infrastructure in favor of constant building of new infrastructure;

- Functional segregation of residential life from commercial life; and

- Increased dependence on the automobile for all work, shopping and leisure trips.

This analysis of the Memphis metropolitan statistical area (MSA) focuses on efficiency issues, including:

- Is sprawl the least costly way to build a functioning city?

- Is society using its limited labor and commuting resources to its best advantage?

- Is a short-run competitive advantage of new suburban malls and neighborhoods a long-run disadvantage in terms of higher infrastructure maintenance expenses?

I examined structure and operation of three components of the regional economy in order to analyze these three issues:

- Physical location of jobs and incomes in the city;

- Costs of commuting by automobile; and

- Costs of providing government infrastructure for the greater metropolitan area.

Background

Modern culture and, more importantly, modern market capitalism have remained primarily an urban phenomena. To protect themselves from the more chaotic elements of city life—crime, congestion and pollution—the growing, home-owning middle class helped create the sprawling suburban city. Sprawl creates a metropolitan area where residences are separated from commerce. And, most importantly, it is a city based on automobile commuting. Some of the reasons cited for relocating to the suburbs include: the ability of residents to choose new homes, better schools and a more homogenous social environment. Much of modern urban economics, as a discipline, is devoted to listing the efficiency virtues of this geographic creation.

But urban sprawl was created at a cost, and those costs are quite large. More importantly, the data imply an alarming characteristic of the modern metropolitan area—it is becoming less efficient. Growth brings a long-term condition of geographic diseconomies of scale, notably in commuting and infrastructure provision.

City Design

The group of researchers and urban planners who investigate alternatives to the sprawling metropolitan city are called the New Urbanists. Their social agenda calls for a new physical design for the city. Specifically, the New Urbanism identifies the car and the vast road system it requires as the key problem of today’s urban organization. In structural terms, the New Urbanists argue for a “planned” physical restructuring of the city, including more mass transportation, higher-density housing and the integration of residential and commercial activities.

The poor physical design of the modern city—Memphis included—is the prime source of rising urban inefficiencies. Is sprawl really inefficient? While it is difficult to argue an emphatic “yes,” given the lack of evidence from a compact urban model, the spiraling cost of sprawl suggests it is a model for city organization whose useful life is on the wane.

Sprawl, as a process, has a life of its own. It is very hard to stop sprawl because of the existence of “network economies.” That is, once citizens, business and government understand how to operate and build a sprawling city based on the automobile, no alternative structural organization seems possible or practical.

The Structure of Jobs and Income

Historically, the city has benefited from agglomeration: the cost efficiencies of businesses being close to another for trade, raw materials, labor and technological sharing. But, sprawl has made that process more complicated. With the functional segregation of residential, industrial and commercial activities, the ability to effectively use the economics of urban agglomeration for economic growth may be at an end.

Memphis has a diversified business economy with a significant focus on medical services, transportation and wholesale trade. Memphis’ industry, particularly manufacturing, trade and services tends to be located in the old city where the number of jobs, the size of business establishments and the earnings per employee are higher than in the suburbs.

Housing data indicate that the suburbs around Memphis are growing more rapidly than the city; they also attract white residents rather than black, have far less poverty and, generally, have higher incomes per household. The city of Memphis is majority African-American. It also is older, has lower per-capita incomes, and suffers from far higher crime rates than the rest of the MSA, i.e., the suburbs. New construction helps identify the functional segregation of the metropolitan area. While three-fourths of the new residential units built in 1995 were in the suburbs, over half the commercial construction and over 95 percent of the industrial construction were in the city of Memphis.

Commuting by Car

In the Memphis area, over nine out of 10 trips are made by car. Public transportation, bicycling and walking are not practical alternatives. There are three costs to commuting:

- Lost and unpaid labor income of driving to and from work,

- Costs of operating a car, and

- Environmental impact of automobile use.

The implicit labor costs of commuting are extremely high. Long commutes (20 minutes or longer each way) make up the largest portion of the cost of work-based travel. In the Memphis MSA, commuting costs add up to $1,278 million per year in lost labor time, a figure that breaks down to $10.41 per day for the typical city commuter and $11.11 per day for the typical suburban commuter.

The explicit costs of operating a car for commuting also are large. Memphis commuters spend approximately $1,685 million per year to drive to and from work. Again, long commutes are responsible for the largest portion of automobile operating costs, and cars are major sources of mobile pollution. Each year, commuting automobiles in the Memphis area place millions of pounds of pollutants into the environment.

Finally, commuting makes up only a minority of all miles driven in the urban economy. The total costs of maintaining an urban transportation network based solely on the automobile may be as much as three times the costs of commuting.

Costs of Commuting to and from Work Each Year

| Memphis MSA Total | Long Commutes* | ||

| Lost Labor Income | $1,278 million | $980 million | |

| Cost of Car Operation | $1,685 million | $1,284 million | |

| Emissions | |||

| Hydrocarbons | 19.5 million lbs | 14.8 million lbs | |

| Carbon Monoxide | 147.7 million lbs | 112.6 million lbs | |

| Nitrogen Oxides | 10.1 million lbs | 7.7 million lbs | |

| Carbon Dioxide | 5.4 million lbs | 4.1 million lbs | |

| * A long commute is 20 minutes or longer each way. | |||

Costs of Government

The costs of financing public infrastructure for the Memphis MSA have risen rapidly as the metropolitan area has expanded east and south geographically. As an indication of the diseconomies of urban scale, during the past decade, debt per person for the three major government entities—the public schools and the local governments of the city of Memphis and Shelby County—has risen rapidly in real dollars. Operating expenditures for the city of Memphis and Shelby County governments also have risen on a real dollars per-capita basis.

While there is no clear pattern of expenditures for road maintenance and construction in Shelby County during the 1990s, expenditures for law enforcement have risen dramatically during a time when local crime rates have not fallen significantly. While the number of schools has declined in the city and risen in the suburbs during the 1990s, education expenditures per pupil for primary and secondary schools have risen dramatically.

Each individual piece of data on urban sprawl is certainly explainable by a number of reasons other than a car-based, functionally segregated urban economy. However, as a whole, the numbers point to one conclusion. The Memphis MSA is an expensive city to operate because of sprawl. Unless action is taken, Memphis’ rising costs for operating the basic infrastructure operating system will continue.

What Is the Cost of Running Local Memphis Area Governments?

| 1999 | 1990 | |

| Population | 870,786 | 827,868 |

| Debt–All Local Government | $2,741 per capita | $1,168 per capita |

| Operating Expenditures | ||

| City of Memphis | $637 per capita | $466 per capita |

| Shelby County | $532 per capita | $600 per capita |

| Critical Social Services | ||

| Law Enforcement | $287 per capita | $161 per capita |

| Road Maintenance | $47 per capita | $69 per capita |

| Public Schools | ||

| City Schools | $6,189 per pupil | $3,831 per pupil |

| County Schools | $4,832 per pupil | $3,038 per pupil |

Future Urban Policy

New Urbanist alternatives to sprawl are straightforward. They recommend the replacement of cars with rapid transit, construction of high-density housing, and mixing of commercial and residential buildings. For the Memphis MSA, those alternatives seem somewhat far-fetched. In addition, urban sprawl in the Memphis metropolitan area is now crossing county and state boundaries so that future regional development planning will become more difficult.

The first step that needs to be accomplished is increasing awareness. Currently, government decisions and development planning ignore the costs of sprawl. Recognizing that geographic expansion has high business/labor and public costs is imperative to future urban design and planning. As long as the community only notices the benefits of sprawl, consideration of alternatives is unlikely.

The second step is to recognize that most of the important decisions regarding the structure of the metropolitan area are outside the marketplace of individual decisions. Expansion of roads, new schools, adequate infrastructure and law enforcement are all social decisions, though they facilitate individual decisions that encourage sprawl. The reduction of urban sprawl probably will be a long-term process of persuading the public that sprawl is inequitable, inefficient and a poor organizational technique for a city. Public decisions to stop financing the engine of sprawl will have to occur before change really can occur at the neighborhood level.

***

Join me at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.