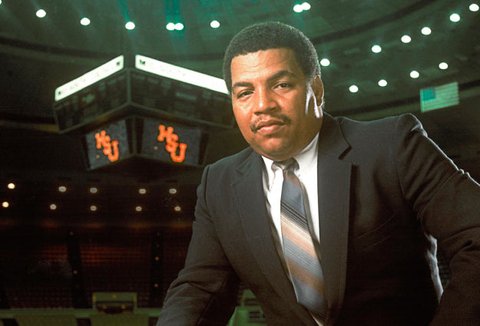

Last week, University of Memphis unveiled its tribute to late basketball coach Larry Finch, one of the city’s most beloved sports figures and whose exit from the basketball program was one of the most embarrassing events in the city’s history.

After bringing the basketball program back from the dead as a player and a coach, he ultimately was fired by insensitive athletic director R. C. Johnson while standing next to a concession stand at The Pyramid.

In 2002, Coach Finch suffered a debilitating stroke and died nine years later.

The University of Memphis’ tribute to a man known for his class, his commitment to his players, and his love of his city includes a statue and panels explaining why he mattered so much to U of M and Memphis.

It was made possible by the commitment by several people, but for me, it began with Memphis Flyer sports report Frank Murtaugh.

The following is the blog post from January 10, 2018:

Memphis magazine managing editor Frank Murtaugh suggested a few days ago that while our attention is focused on statues, we should consider one for Larry Finch.

Some people said that Mr. Murtaugh was being kind to remind us about the man and the movement that was Mr. Finch, one of the best players to ever don a Memphis State University basketball uniform and later was successful head coach for his beloved school for 11 years from 1986 to 1997. But it wasn’t kindness that inspired Mr. Murtaugh but fairness and recognition for the role model that Mr. Finch was for so many.

After garnering more than 20 wins in seven of those years, including the two before his 16-15 record in his last year as coach, he was forced to resign by the athletic director at a Pyramid concession area in the shabbiest episode in the university’s athletic history.

I was a student at University of Memphis during the miserable year of Coach Moe Iba’s 6-20 season in 1969-70 (it followed his two previous season’s records of 6-19 and 8-17) and how the recruitment of Larry Finch promised a new day for the basketball program.

Symbols Matter

Mr. Iba wasn’t around to see the turnaround, having been replaced by Gene Bartow, who, in his way, was the coaching equivalent of Mr. Finch. The year after Mr. Iba had won only six games, the Bartow-Finch team had a record of 18-8 and only a couple of years later would play for the NCAA national championship.

His play is indelibly etched in my memory – his jump shot leaning into a defender and banking in a shot as the buzzer. With seconds on the clock and with the last shot on the line, the ball always went to him…and he wanted it.

But he was so much more. He was the kind of player who always, always had times to talk to children and to play a pickup game in his old neighborhood. He was the kind of player who cried on senior day because he could not fathom not playing for his university and his city.

And yet, his game winning shots and records were only the Melrose High School star’s accomplishments on the court. Even more remarkable for those of us who remember those days, he was a symbol that Memphis desperately needed.

Just as the Iba record symbolized the city’s malaise, despair, and depression following the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the emergence of Larry Finch spoke to an optimism and positive attitude that had impact throughout the city. Through the force of his personality and the respect that rallied around him, he became a reassuring symbol to a future that could be better and a city that could be united.

Nobility and Love

This does not mean that his example could single handedly usher in solutions to long-festering racially-based issues or to the white flight that would begin in earnest during his college playing career as federal court ordered a busing plan to end segregation in Memphis schools.

However, his engaging smile, accessible demeanor, and his “never met an enemy” approach to life were a model at a time when Memphis needed a hero and some confidence about the future.

In other words, we wholeheartedly second Mr. Murtaugh’s 10-year campaign to have a statue erected in honor of one of Memphis’ noblest citi zens and someone whose love for his hometown was a motivating part of his life.

zens and someone whose love for his hometown was a motivating part of his life.

After all, for as long as I can remember, we have said Memphis is a “basketball city.” It’s time to erect a statue that celebrates that fact, and there’s not one that does this better than one of Mr. Finch.

It Should Be Done

Even after a debilitating stroke that put him in a wheelchair, “Coach” remained the classiest person this city had ever produced and died much too young at 60 years old in 2011.

Mr. Murtaugh best makes his own case, and I encourage you to read his Memphis magazine column. As he said so well, it’s a chance for the debate about statues representing racism to be replaced by one in the most prominent location possible to salute a unifying force in Memphis’ recent history – Larry Finch.

Mr. Murtaugh writes: “As for how . . . contact your favorite Memphis booster. This remains a small town. Anyone remotely close to the Tiger program knows a booster with deep pockets. Surely enough could be collected to pay the right sculptor to bring Larry Finch (and his magnificent jump shot) to life once more. The handsome statue of blues legend Bobby “Blue” Bland that now stands on Main Street cost upwards of $50,000. This can be done. And it should be done. Memphis has cleared itself of imagery that divided for decades. Let’s create an image that will unify and inspire for decades to come.”

This also is a good chance for University of Memphis to right a wrong, and we hope it will take a place at the front of this campaign.