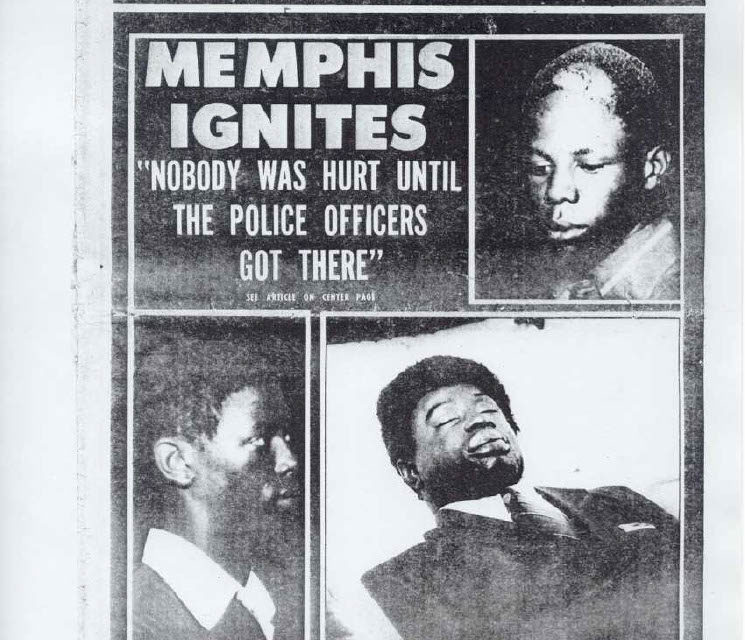

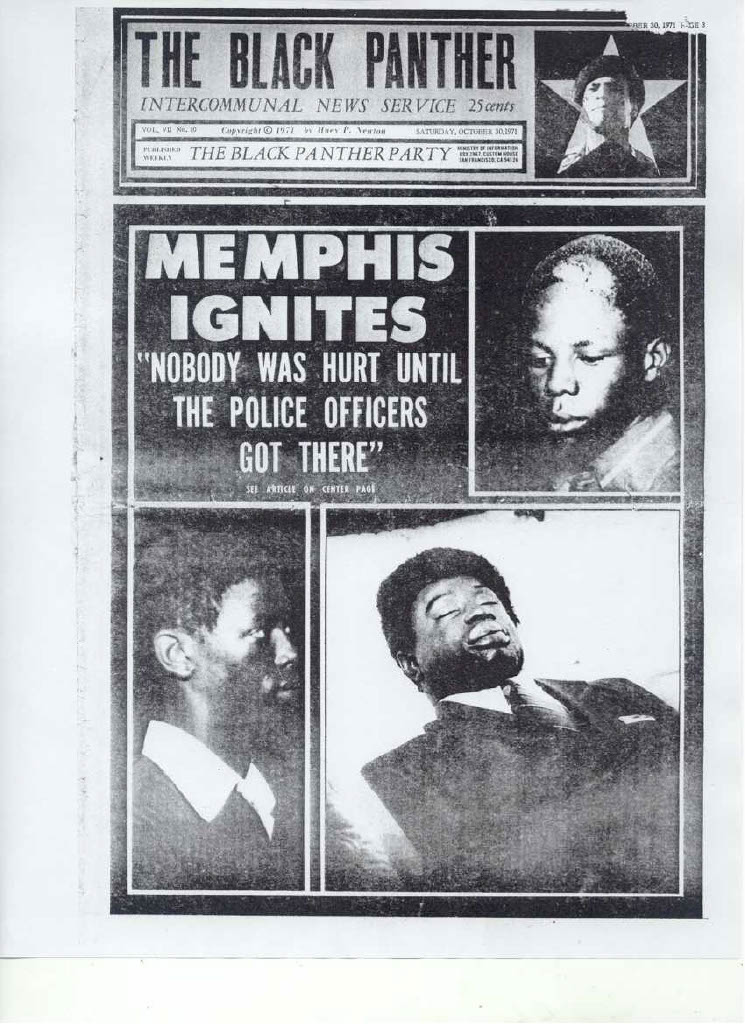

“Nobody was hurt until the police officers got there.”

Part I: The Introduction to a Teenager’s Murder.

Today: Part II – The Incident.

Next: Part III – The Trial and Part IV – The Outcome and Aftermath.

**

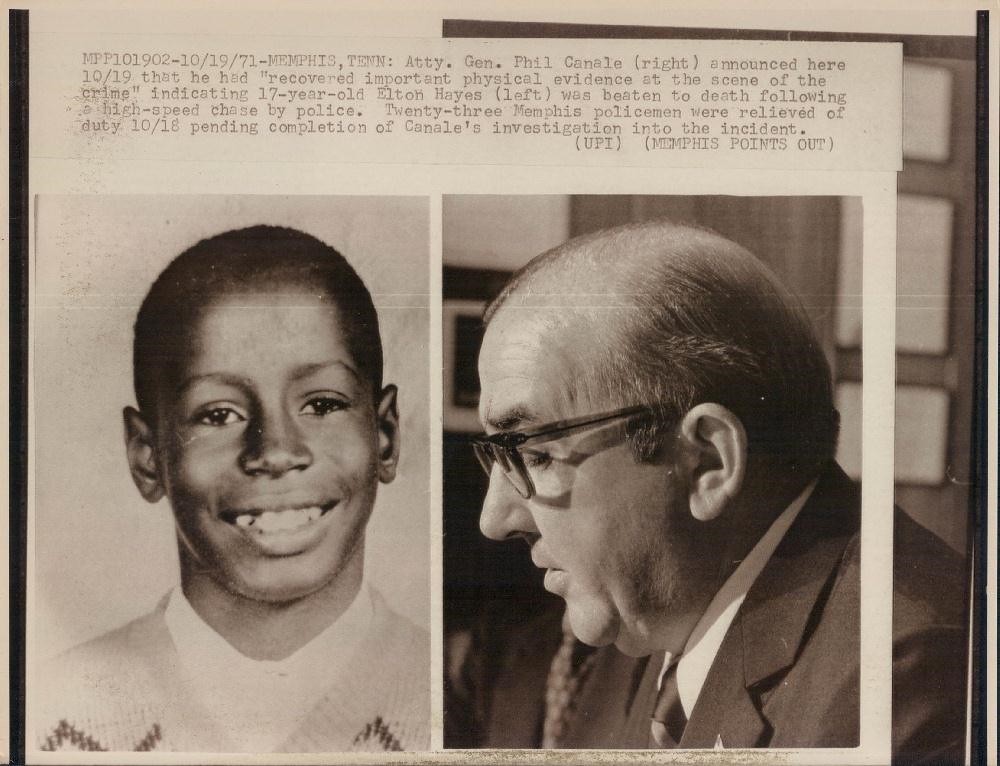

By the time the indictments were returned on December 9, 1971, there was no dispute about the facts about the way Elton Hayes had died.

The 17-year-old was killed October 15, 1971, at the end of a five-mile high speed chase that began at South Parkway East just west of Castalia and ended in a ditch at highway 78 and Stepherson in Capleville. He was a passenger, along with 14-year-old Calvin McKissack, in a Chevrolet pickup truck driven by their friend, 15-year-old George Barnes. The truck was owned by Mr. Barnes’ father, Arzell, and the younger Barnes did not have a driver’s license nor did he have permission to use the truck.

The chase began at 1:55 a.m. when police said they spotted a pick-up truck making a u-turn. Mr. Barnes said he panicked when a police car pulled up behind him but he made no mention of a u-turn.

The chase through Memphis was joined by other police after officers in the first cars radioed that they were being forced off the road by the truck. When the chase reached Capleville, Mr. Barnes said he pulled the hand brake and the truck slid halfway into a ditch. By then, they were being followed by a caravan of police cars with sirens blaring and blue lights flashing.

Shortly after the truck came to a stop, there were 34 policemen on the scene and many rushed from their cars to the ditch where the three boys were pulled from their vehicle. Twenty-five police officers would be relieved without pay by Memphis Police Chief Henry Lux, a decision African American City Councilman J. O. Patterson Jr. called “a paid vacation.”

“We knew we were going to have to take a beating,” Mr. Barnes said. “Three Negro boys in a truck, beating them in driving, them in their fast cars. They had to beat us. There wasn’t any wreck. We just slid into the ditch.

“Nobody was hurt until the police officers got there. I grabbed my head and they began poking me in the ribs with sticks. I could see policemen on their knees in the ditch, swinging their sticks up in the air, but I couldn’t see who they were. Then, they knocked me down and started kicking me in the side and stomach. I never heard anything from Calvin or Elton. All I could hear was cops calling us everything but a child of God.

“When I got up, they were still swinging the sticks, but I didn’t know on who. They carried somebody out of the ditch and put them in the sheriff’s car and let out for the hospital, I guess. They cussed us all the way to town, and one time, one of them spun around in the seat, shook his finger, and said, ‘Don’t you know if you had killed those two officers in that car, it would have been worse for you than raping a white woman? We’d sure enough killed you and left you laying where you fell.’”

Mr. McKissack said: “All I saw was blue shirts and nightsticks. They were cussing us, calling us niggers; beating up on us. I heard Elton on another side of the, truck, saying, ‘It wasn’t me, it was George (who was driving the truck), it was the other guy. Then I didn’t hear Elton any more.”

At one point, Mr. Barnes said he became aware that a Black sheriff’s deputy was standing above him with a foot on his face. The officer, Lt. Wilks, apparently took command at that point because Capleville was outside the jurisdiction of Memphis Police Department. It was said that he insisted on getting prompt medical attention for Elton Hayes and refused to cooperate with policemen who were concocting the story that his severe injuries were the result of a traffic accident. Lt. Wilks was reported to have told the policemen that he was going to say in his report that the truck was undamaged.

Mr. Hayes’ death was the match that ignited a simmering powder keg of resentments and anger in Memphis’ African American community. Just over a year earlier, The New York Times reported on July 4, 1970, that eight people had been shot and killed by policemen in the previous five months and they were using a variation of dumdum bullets.

Before the investigations in the 1970 shootings were even complete, Police Chief Henry Lux said the officers “had no choice” in the fatal shootings. City of Memphis Director of Safety Frank Holliman said: “As long as that gun is on the hip of a policeman, it’s there for killing.” He would later add that he had never heard of a brutal policeman.

The Memphis NAACP held six hearings on the administration of justice, focusing on police brutality, bail bond reform, street crime, and court reform. Despite the growing concerns, nothing really changed in law enforcement’s attitude toward Black defendants.

The Memphis NAACP held six hearings on the administration of justice, focusing on police brutality, bail bond reform, street crime, and court reform. Despite the growing concerns, nothing really changed in law enforcement’s attitude toward Black defendants.

Two months after Mr. Hayes’ killing, on December 13, 1971, the federal grand jury began hearing testimony about two unrelated police abuse cases, but after four days of hearings, no indictments were returned. Twenty-five policemen had been subpoenaed to testify and at least one of them invoked his Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination.

The federal grand jury hearings were seen by many as an attempt to defuse additional protests about the unequal treatment of Blacks stopped by the police.

It would not be until the second anniversary of Elton Hayes’ death that the trial began for the three sheriff’s deputies and a Memphis policeman charged with first degree murder, four city policemen charged with assault to murder, and one police inspector charged with neglect of duty.

I was the Memphis Press-Scimitar reporter on the court beat when the case came to trial, and day after day, stories about the trial were published on the front pages of two Memphis’ daily newspapers. The Press-Scimitar placed it high in all three daily editions which had deadlines at 7 a.m., 11 a.m, and 2 p.m.

Jury selection began on October 15, 1973, in the courtroom of Criminal Court Judge W. Otis Higgs Jr., the only Black criminal judge in Tennessee. It would continue for 13 and a half days.

Before a jury was chosen, 1,844 Shelby Countians had been summoned as prospective jurors. Many of them were excused because they had reached opinions on the law officers’ guilt. At the same time, lawyers for the officers rejected African American after African American until on October 30, when 12 jurors and three alternates – all white men – were sworn in to hear the case.

The trial would last seven weeks, the longest trial in Shelby County Criminal Court at the time. Judge Higgs rejected defense motions to delay the trial for six months and to try the officers charged with murder separately from those charged with assault.

Finally, it was time to hear the evidence from prosecutors and responses from defense attorneys.

Next: Part III – The Trial