“I told them we’re either going to get jumped on or hauled to jail or get killed.”

Part I: Introduction to a Teenager’s Murder.

Part II: The Incident

Part III: The Trial

Part IV: The Outcome and Aftermath

**

After spending 13 ½ days selecting a jury, the trial of the law officers charged in connection with the beating death of 17-year-old Elton Hayes and the beating of a 14-year-old friend finally began October 30, 1973. It was two years and two weeks after the early morning when Mr. Hayes was killed after a five-mile, high-speed chase.

The trial would feature a parade of police witnesses with only a couple providing any useful information, a missing tape of police radio conversations, the judge dealing a blow to the prosecution’s case against the law officers, and a defense attorney vilifying the teenage victims as criminals. All in all, as the trial unfolded, it fed suspicions that justice would not be done.

In his opening statement, the attorney for two city patrolmen attacked the victims, saying the three teenagers were drunk and should have been indicted. They were “guilty of a number of crimes during the chase and after the case…They tried on more than one occasion to crash into the squad car and kill or injure them (police).

“Before you worry too much about poor Barnes, poor McKissack, or poor Hayes, listen to the proof as to what crimes these three individuals were committing. Keep in mind that these young men (police) when they put on a badge, are not endowed with superhuman strength, patience, or judgement. We can all say two years later, maybe it would have been better to do this or that. We’re not faced with the situation of a felon fighting you down in a ditch.”

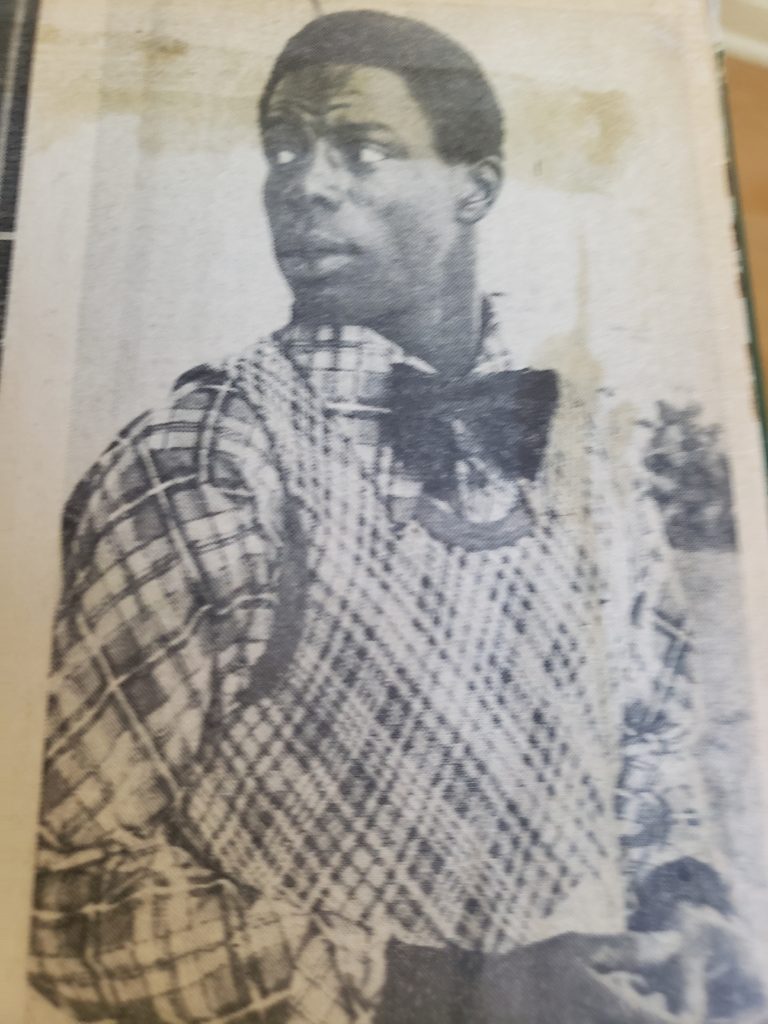

And so it went as the three African American teenagers were described in the starkest, most damning terms. Elton Hayes was a passenger in the truck driven by his friend, 15-year-old George Barnes, and accompanied by their friend 14-year-old Calvin McKissack. Mr. Barnes did not have a driver’s license or permission to drive his father’s truck, and if they were guilty of anything, it was being joyriding teenagers, however, before it ended at about 2 a.m., Mr. Hayes had paid with his life.

Three sheriff’s deputies – Lt. Theodore R. Wilks and Patrolmen Edward M. Bonham and Johnnie L. Roberts – and one city policeman – Michael J. Dougherty – were indicted on first degree murder charges. Four city policemen – Danny L. Davis, Larry R. Skelton, James B. Dyer, and William L. Graves – were charged with assault to murder in the beating of Calvin McKissack, Mr. Hayes’ 14-year-old companion in the truck. Police Inspector H. R. Ray was indicted on a charge of neglect of duty, a misdemeanor. All of the defendants were White except for Lt. Wilks.

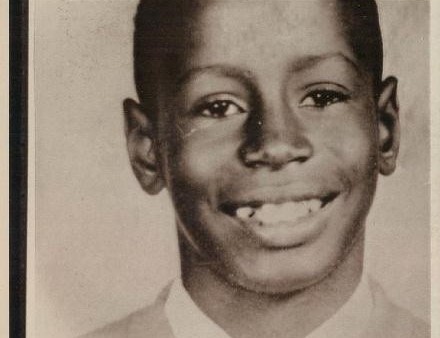

The prosecution’s first witness was Mr. Hayes’ mother, Mrs. Gussie McGowan. She said she had never seen her son drink, and although she had smelled alcohol on his breath before, she had never seen her son, who was six feet tall and weighed 168 pounds, drunk.

When she arrived at John Gaston Hospital at 5:30 a.m. October 15 following her son’s beating, she said he was unable to talk to her. “They came by me with him on a stretcher. He was all bloody and swollen. They said there wasn’t anything they could do – that he didn’t have a chance.”

Her son dropped out of school in the ninth grade and had worked at a department store but had quit to find a factory job. The Monday before his death, he had visited an employment office and applied for a new job, but was told to return in a month later after his 18th birthday.

The second witness, Dr. James Bell, assistant Shelby County medical examiner, testified that Mr. Hayes died from nine blows to the head. Six were strong enough to cause brain damage and four were sufficient to crack his skull. Dr. Bell said three holes had been drilled by surgeons in the teenager’s skull to remove fluid and relieve pressure. He said that Mr. Hayes’ blood alcohol level would have been .10 to .18 at the time of the incident. Under state law .10 is the limit set on the ability of a person to drive safely a vehicle.

Patrolman E. L. Mullins said he was involved in the chase and loaded his shotgun in hopes of shooting out the truck’s tires because the vehicle had tried to ram his patrol car. He was riding with Inspector James B. Dyer who swerved to miss the truck, ran onto the median at Lamar and Prescott and blew out two tires. “Up until the time the chase reached Lamar, there was nothing involved except traffic charges,” he said, adding that he thought the truck’s driver was trying to ram his car.

It was at this point that police emotions escalated when Patrolman Mullins made a radio call: “I broadcast that a pickup truck was trying to ram our squad car.” Other police cars responded and joined in the chase, which likely terrified the teenagers whose evening began with hopes for a joyride but had now become a chase by police cars with sirens wailing.

Mr. Barnes testified that he could not identify any lawmen involved in the incident. “When you see somebody coming at you, you don’t look at him so you’ll know what he looks like if you see him again. You don’t want to see him again.”

He said Mr. Hayes was not injured when the truck slid into a ditch on Stepherson Road. They turned and saw officers coming after them. “I told them (Mr. Hayes and Mr. McKissack) we’re either going to get jumped on or hauled to jail or get killed.” He was pulled from the truck and one of six white officers pushed his head against the vehicle and knocked him to the ground. At that point, he could see officers’ arms and sticks “moving up and down.”

Prosecutors said that the law officers mistakenly thought Mr. Hayes was driving the truck, which was why he became a target for the most brutal beating.

Mr. Barnes said he was ordered to get up but as soon as he did, he was knocked down again. A tall, Black officer put his foot over his eyes and a short policeman cursed him and struck him on the knee with a nightstick. He was then thrown into a police car where he placed his head between his knees.

“When I raised up again, they were bringing Calvin (McKissack). They just threw him in. Calvin started crying and told me to ask them if they could take handcuffs off because he thought they had broken his shoulder.” The police removed the handcuffs. He was taken to John Gaston Hospital and later to Juvenile Court at 6:30 a.m.

Mr. McKissack testified in a voice so low spectators strained to hear him, saying that after he was ordered to step out of the truck with his hands up, he was hit in the head, shoulders, and knees. He said that Mr. Barnes tried to outrun the police because he didn’t have a license and “he didn’t want to lose his daddy’s truck,” but after more police cars joined the pursuit, he said Mr. Barnes said that he was going to stop because “I don’t want to kill nobody.”

Patrolman Harold Sanderson testified that he saw Michael Dougherty, charged with murder, and William E. Graves, charged with assault to murder, “swinging nightsticks” at the scene of the fatal beating of Elton Hayes. A second policeman, R. C. Kennedy, said he saw two city patrolmen swinging nightsticks and a sheriff’s deputy holding a nightstick. He said he saw Patrolman Bonham holding a stick and walking toward Mr. Hayes and that Patrolmen Dougherty and Davis were swinging nightsticks at two youths. Patrolman James S. Smith testified that he saw Mr. Dougherty and Mr. Graves swinging nightsticks in the ditch and saw Lt. Wilks return a nightstick which he apparently had gotten from his squad car. Their testimony followed a dispatcher who said there was a “missing tape” of the police’s radio calls because of equipment malfunction.

The prosecution’s case took a devastating turn when Criminal Court Judge W. Otis Higgs excluded from evidence five confessions by sheriff’s officers because the attorney general’s office had not provided them to defense attorneys in a timely manner. Prosecutors contended that they had complied with Tennessee law. The unhappy judge, the only Black criminal court judge in Tennessee, understood the implications of his ruling and how it benefited the defense team. “The eyes of the community are upon us. The position I’m being put in makes it appear I’m defending the law officers on trial. I don’t like that position, gentlemen. I’m unconcerned about the prosecution or defense. I just want to make sure the defendants have a fair trial.”

Prosecutors continued by calling a parade of police witnesses who had arrived at the scene. Captain Earl Clark, commander of the east end, said 10 cars were already there when he arrived and he did not recall saying, “Get him (Mr. Hayes) out of the road before the news media gets here?”

Patrolmen Michael J. Dougherty and Edward M. Bonham were the only defendants to testify. They were charged with the murder of Mr. Hayes but said they did not kill him. Mr. Bonham said he ran into a clothesline while checking the area and fell. After finding his eyeglasses and nightstick, which he had lost, he began walking toward the ditch where he saw two groups with eight to 10 officers in each in the ditch with the teenagers. He said the only time he touched Mr. Hayes was to use his nightstick to prevent the youth from “gouging” out a wound.” Patrolman Dougherty said he was at the murder scene no more than two minutes, he remained near his squad car, and he never saw the youths.

After Judge Higgs refused to direct not guilty verdicts, defense attorneys blamed Mr. Hayes’ killing on a policeman who was not charged in the case but testified against the defendants.

After calling 86 witnesses and introducing 364 exhibits, the prosecution rested.

The prosecuting attorneys acknowledged the lack of strong testimony as only a couple of the 25 police witnesses were helpful to their case. Most of the damaging testimony during the seven-week trial concerned Memphis Patrolman Michael Dougherty charged with first degree murder. Three police witnesses said they saw him in the ditch swinging his nightstick. None of the police witnesses saw the sheriff’s deputies, Lt. Theodore R. Wilks Jr., and Patrolmen Johnnie L. Roberts and Edward M. Bonham strike Mr. Hayes although they were charged with first degree murder.

All in all, the prosecution would have been wise to trim their case down to its essence. In their zeal to be comprehensive and thorough, they confused things and eliminated a clear through line for a memorable narrative for the jury. It led to some suggestions that the prosecution intentionally muddied the case as part of a corrupt justice system that set out from the beginning to make sure no law enforcement officers would be held accountable for taking the life of the 17-year-old teenager.

Next: Outcome and Aftermath