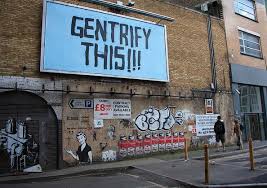

The conversation about gentrification continually repackages a set of debunked theories as reality and it obscures a set of real crises that need fixing.

By Brett McMillan

Published in Shelterforce

Gentrification has become a functionally useless term.

I don’t know when exactly I reached my breaking point on this issue, though I have been gradually phasing it out over four-plus years of studying neighborhood change. My guess is that it came somewhere between a ridiculous 2019 Jacobin article that claimed that graphic novels “are comic books, but gentrified,” or the turn in this summer’s Black Lives Matter protests when I started watching white people my age parade through Brooklyn screaming “fire, fire, gentrifier.” Whether they arrived here by birth or migration was impossible to tell, but at any rate it would have been impossible for them not to have ridden here on the ongoing “gentrification” wave that originated in the 1980s. If only we millennials had the ability to own our glass houses like so many NIMBY boomers did.

This is all to say that we have a major problem with how we talk about gentrification in this country, a fact true for people all across the political spectrum. First, because the conversation continually repackages a set of debunked theories as reality, and second, because it obscures a set of real crises that need fixing, namely, neighborhood-level inequality, the disappearance of affordable housing, and wages that have lagged behind the rising cost of shelter.

Let’s start by separating gentrification theory from reality. I’ll begin with the common narrative of gentrification, in which wealthy white people and developers move into poor neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color, directly displacing residents with the erection of new, fabulous apartments. This theory was introduced to the U.S. in the 1970s by geographer Neil Smith, but again it was a theory for explaining a new demographic pattern of people moving back to the city from suburbs—a hypothesis unconfirmed, something to be tested. Study after study that has tested it since, the best among them coming from scholars like Lance Freeman and Ingrid Gould Ellen (also, the Federal Reserve) find the theory insufficient.

Beginning with displacement, in a 2005 study covering over 31,000 households from 1980 to 2000, Freeman found that “mobility out of gentrifying neighborhoods is not necessarily dramatically different from mobility out of other neighborhoods.”

A little over a decade later, Ellen also found no significant differences in mobility among low-income residents who lived in gentrifying neighborhoods when tracking over 35,000 New York City children enrolled in Medicaid and who lived in market-rate apartments from 2009 to 2015.

Lastly, Quentin Brummet and Davin Reed, writing in 2019 for the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, found “moderate,” 4-6 percentage-point increases in mobility rates among less advantaged residents of gentrifying neighborhoods from 2000-2014 (the baseline mobility rate among all renters in the study was 70-80 percent), using a sample population of over 170,000 adults and children and a definition of gentrification based on educational attainment. Rather optimistically, their study also suggested that people who did move from gentrifying neighborhoods seldom ended up in worse-off locations, and that gentrification “creates some important benefits for original resident adults and children and few observable harms.” I’ll offer more on the half-truthfulness of this statement later on.

Next I’ll tackle race, where data along the Black-white fault line of urban segregation runs almost exactly counter to Smith’s theory: It has been the rare exception, and not the rule, to find white people moving into majority-Black neighborhoods. A 2014 mixed-methods study by Jackelyn Hwang and Robert Sampson found that Chicago neighborhoods with Black populations of greater than 40 percent experienced significantly lower rates of gentrification. (They also found that substantial Hispanic populations in neighborhoods that were less than 40 percent Black adversely affected gentrification’s likelihood, too.) In 2015 Lance Freeman and Tiancheng Cai observed that white “invasion” into Census tracts with Black populations of 50 percent or more has been a relatively infrequent phenomenon going back to 1980, though they also observed a slight recent uptick in its occurrence: Per their analysis of thousands of Census tracts across the country, 5.49 percent of tracts that were at least 90 percent Black and 10.44 percent of tracts that were at least 50 percent Black experienced an influx of white residents from 2000 to 2010, compared to 0.39 percent and 4.71 percent, respectively, from 1990-2000.

These results corroborate Stacey Sutton’s findings in a 2020 paper focused on New York City, a place that she acknowledges as exceptional for the tightness of its housing market. Her paper suggested that in 2010, for the first time, the average gentrifying neighborhood in New York City was not majority white but instead 52 percent Black and Latino. The next question that logically follows is whether this signals potential racial transition, or the substitution of White neighborhoods in the place of formerly Black ones, in gentrifying areas. So far, research indicates that in New York City—an outlier when it comes to whites moving into Black neighborhoods—stable integration has been a much more likely result. (Of course, New York also has some of the most robust affordable housing programs in the country, meaning that a free market does not guarantee these outcomes alone.)

Finally, a lack of new construction—not an excess of it—in places like New York and San Francisco drives up housing prices. A 2019 review of the research on supply-side skepticism offers a thorough refutation of many of points held up by anti-development advocates. As Vicki Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine O’Regan write, “new construction is crucial for keeping housing affordable, even in markets where much of the new construction is itself high-end housing that most people can’t afford.” Most evidence suggesting differently, they continue, is anecdotal rather than causal, and frequently fails to take in account decades of backlog in the construction of new housing supply: A new building will not immediately lower prices if a city is already thousands of housing units behind projected demand. A paper published last month tried to finally put a number on the effect that new construction has on local housing prices using data from 11 major cities that included Atlanta, New York City, San Francisco, and Washington D.C. The researchers found that new market-rate buildings in low-income neighborhoods decrease local rents by 5-7 percent.