One year ago, more than 150 nonprofit organizations signed an open letter setting out an agenda to reform criminal justice, reduce police violence, fight systemic racism, and some demands involving governmental processes.

One of those other demands was to “enact a citizen participatory budgeting process at the city and county level beginning with FY22 budgets in partnership with Memphis City Council and County Commission that prioritizes neighborhood-level investments.”

The letter was addressed to Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland, Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris, Police Director Michael Rallings, Sheriff Floyd Bonner, Greater Memphis Chamber CEO Beverly Robertson, Shelby County District Attorney Amy Weirich and all 26 members City Council and County Commission.

There are arguments for and against participatory budgeting. With the help of a City Council member, there’s the opportunity to test it here.

Is Everyone Involved?

New York City Council boasts that “participatory budgeting is democracy in action.” The process allows citizens to vote, usually in focus groups, on how they want a specified part of the city’s budget to be spent. It’s a way to give power to people who aren’t normally engaged in the political process, according to the New York City Council website.

However, research suggests that the process favors people with the resources to get involved and to lobby for their projects and that extremely poor people are often underrepresented. More to the point, some people complain that these contests over relatively small amounts of money can become distractions for activists who could have broader and greater influence in the political system.

Of course, some things wouldn’t be left up to a vote, things like a new library in Raleigh, a new community center in Frayser, after-school programs, and safe parks, for example. They are the kinds of things built into the budget as a reflection of a city’s aspirations for itself.

Here, aspirations are often complicated by the tens of millions of dollars in deferred maintenance left unaddressed in public budgets for many years (if not decades), and this need may find it hard to compete with the kind of “sexy” priorities that would attract citizens’ votes.

Further complicating participatory budgeting is that almost every public service here, except for law enforcement and fire protection, are underfunded when compared to peer cities. That said, if participatory budgeting could draw voters’ attention to this structural problem, it might build momentum to increase budgets to a meaningful level and pass the taxes to fund it.

Hurdles To Clear

If participatory budgeting (PB) could be designed to provoke innovative policy, to elevate public understanding of the challenges to budget-making, and if inequalities like power and resources were addressed to make the process fair, it could be a worthwhile process that results in greater public awareness and involvement by citizens in the governments they own.

In Brazil, where participatory budgeting was first developed in the 1980s, many cities followed Porto Alegre to institute their own PB processes, and by 2001, more than 100 cities in Brazil had implemented it. Since that time, the number of cities has fallen by more than 50% and even in Porto Alegre, its future is uncertain.

It speaks to the challenge of keeping the public engaged over a sustained period of time. The experience of participatory budgeting is that it works best when the government has access to flexible funding of a size that attracts people to the process. It works best in early years when the public is excited about the opportunity to be part of the unique approach to budgeting.

Over time, process fatigue sometimes sets in and some people complain that expectations exceed what the process can deliver as ideas hit the realities of what money is available to fund them. In addition, in Brazil, participatory budgeting tended to be associated with a specific political party and as a result, PB’s decline mirrored the decline of the party’s influence across Brazil.

That does not mean that participatory budgeting is being abandoned. In a 2019 census on participatory budgeting, it claimed it was being used in 11,000 places. Others claim it is closer to 1,500 worldwide.

How It’s Done in NYC

Regardless of how participatory budgeting is performing in other cities, enthusiastic advocates remain in New York City. When it began in 2011, only four Council members participated in the process “to allow residents in their district to allocate part of their capital discretionary funds.

By 2019, 33 Council members – there is a total of 51 members – participated in a process giving residents the ability to allocate at least $35 million in capital funding (the total New York City budget is more than $100 billion). After several phases, projects with the most votes during a nine-day Vote Week are folded into the city’s budget for physical infrastructure projects that cost at least $50,000 with a lifespan of at least five years. These can include improvements to schools, parks, libraries, public housing, streets, and other public spaces.

The schedule in New York is:

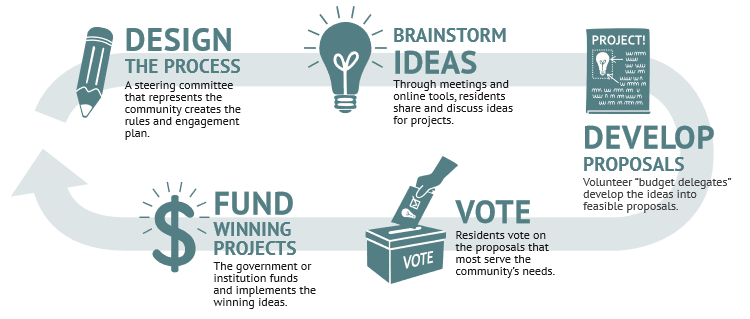

* August – October: through community meetings, residents brainstorm ideas and recruit Budget Delegates in the current cycle

* October – January: budget delegates transform ideas into full proposals, with support from city agencies and staff. Delegates narrow down proposals and select projects that meet the needs of the community.

* March – April: once proposals have been determined, budget delegates and residents get out the vote and prepare for a nine-day community vote.

* May – June: winning projects are included in New York City’s upcoming fiscal year budget. Staff and stakeholders evaluate the process and oversee the implementation of winning projects by agencies.

Pilot Program, Anyone?

All this is prologue. Two days ago, Memphis City Council approved $2.6 million to be split between the 13 of them so they can award grants to nonprofit organizations.

Rather than making these decisions on political factors like favorite projects or relationships, what if a Council member or two put their $200,000 of grant money into a pilot program of participatory budgeting for their district?

It’s a way to test the concept of participatory budgeting and evaluate the results.

That’s would be more than just participatory budgeting. That’s also participatory politics.

**

Note: The resolutions for the nonprofit grants, the certified tax rate for City of Memphis, and authorization for city treasurer to prepare tax bills all had a request for “same night minutes.” Jimmie Covington has written about the use by Memphis City Council of this questionable tactic which he says is not used by any other governing body in Tennessee.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.