In 1986, minority business development was an afterthought – if thought of at all.

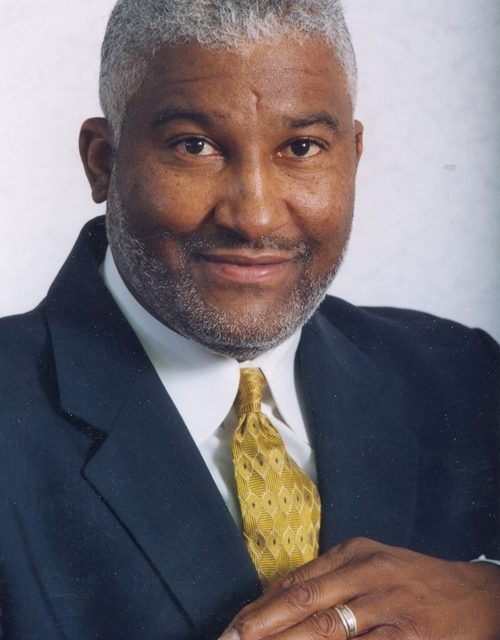

That would all change when Melvin Jones, a Cornell University law graduate, moved to Memphis and took up the cause. It was a 34-year passion that only ended with his death last Sunday, November 15. He was 65.

Passing up a promising – and personally lucrative – career with a white shoe law firm in St. Louis, he struck out to do something that was more fulfilling and would be a legacy that showed his life had made a difference.

His passion gave birth to the Black Business Directory in May 1986, which became the master list of African American-owned businesses in this community. Its visibility and his advocacy put minority business firmly on the priority list for Memphis and Shelby County.

To propel progress, five years ago, he created Memphis Business Contracting Consortium which insisted on a bigger Black middle class to expand the economy. He said that if 10,000 African American families could earn an additional $10,000, it would be $100 million of additional annual income, or three new Electrolux plants, and reduce poverty.

Along the way, he had also published PROUD magazine which celebrated African American culture and reminded everyone of our debt to its impact on Memphis’ character.

The Champion

All of these milestones are the tangible achievements of his life, but what I admired more than that was the intangible. It came from his relentless focus on creating more Black-owned businesses and increasing their revenues.

In the Tri-State Defender (where he was once interim editor), Carlee McCullough, former Contract Compliance Officer for former Mayor Willie W. Herenton, described him perfectly: he was outspoken, unapologetic, and a bold champion for minority business.

If he had simply published his directory and seen that as his mission, he could have lived the quiet, comfortable life of a publisher. But he understood that was only part of his purpose. In addition, it was his role to be an authentic African American voice unafraid to confront unpleasant truths about Memphis and Shelby County and to challenge our community to do something about minority-owned businesses, not just talk about them.

All in all, he had no tolerance for lip service. He recognized it for what it was – patronizing promises that pushed off real change.

Like many independent Black men in Memphis who speak their minds, he paid a price for it. Some people in positions of power considered him a nuisance, strident, and unreasonable.

What they failed to understand was that he was speaking honestly through the lens of a Black man in Memphis and expressing the opinions of many. It was not his calling to make them feel comfortable. Rather, he felt an obligation to push the envelope rather than act Southern (don’t upset anyone, smile, and go along to get along).

A Messenger of Truth

Because of it, he would speak truth to anyone with the power to influence and change things – mayors, City Council members, County Commissioners, CEOs, economic development officials, and anyone else who could join in his crusade for equity. But most of all, he spoke for Black business owners.

Referring to local companies in 2016, Melvin said: “Historically, they have never hired African American firms.” That he was still having to say this 30 years after he moved to Memphis says volumes about the inertia here and the need for dramatic progress.

His message was clear. It was also prescient.

If Memphis was to become successful, it had to unleash the power of minority business as a force to reduce poverty. As Shep Wilbun, Shelby County Government’s chief supply diversity officer, told The Daily Memphian, he was “a person who was perpetually committed – and I do mean perpetually – to insuring Black folk were included in the economics of this community.”

Truth be told, the job of county chief supply diversity officer probably owes a debt for its creation to Melvin. It was his uncompromising and persistent advocacy that changed the local vocabulary and in time changed behaviors.

Moving Beyond Platitudes

More needs to be done, but that does nothing to diminish how far he moved the ball.

I first met Melvin roughly 10 years ago when I had asked him to speak on a panel about marketing Memphis at a Leadership Memphis Executive Class meeting. As I recall, another panelist was Kevin Kane, president of Memphis Tourism, and one other person whose name I can’t remember, and both of them delivered the kind of boosterism comments they were paid to deliver.

When it came to Melvin, he immediately became animated, pointing out that there was little connection between the Memphis of marketing and the Memphis of reality, the Memphis of poverty, of need, and of inequitable distribution of power and money.

He prosecuted the case using every skill he had learned from the highly skilled professors at Cornell Law School, one of the highest rated law schools in the U.S. He was emotionally engaged and convincing, and yet, it was easy to feel the tension in the room among class members.

Clearly, it was the first time many had seen Memphis through the eyes of an African American man who wanted them to move beyond platitudes to progress and beyond talking points to action. The reaction for most was not to embrace this rare opportunity to walk in another person’s shoes but to be peeved that he had ruffled some feathers.

Truth Teller

It did not deter Melvin who continued the same missionary work in every corner of the community. He described the purpose of the Memphis Business Contracting Consortium as “powerful, yet simple”:

“The economy of Memphis lags far behind cities of equal size. Those cities continue to expand their financial lead and will continue to do so if we do not demand and create more opportunities for African American businesses.

“All too often, the African American-owned businesses located in Memphis are not given the opportunity to participate in many critical financial transitions affecting this area. Major multi-million dollar contracts are awarded to out-of-state companies and talent is utilized from other areas when there is local talent and local companies that are fully capable of doing the work.

“Those companies then take those dollars back to their respective communities and spend them there. This unpublicized ‘boycott’ of the African American community and its businesses permanently dooms the prosperity of metropolitan Memphis.”

It’s hard to think of a stronger epitaph than that for Melvin Jones.