Thumbnail: The Overton Park Conservancy continues to map out the future of Memphis’ beloved park and is asking for public input. Overton Park is at a crossroads and it’s in everyone’s interest to help make it be all that it can be. About 10 years ago, we had an opportunity to express opinions that led to creation of the Overton Park Conservancy. Your input can help define the park’s next chapter.

**

It’s easy with 186,000 square feet of space looming over you – in the form of Memphis College of Art and Memphis Brooks Museum of Art – to take your eye off the ball.

And yet, the really important decisions to be made – and which may in fact lend themselves to new uses for the buildings – are about the parkland’s future itself.

It’s good to see that the Overton Park Conservancy remains focused on that.

The three questions asked by the Conservancy when it officially kicked off its Parkwide Master Plan 2018 remain pertinent and their answers just as definitive:

1) How can we make the park equitable for all Memphians?

2) How can we honor the historic and present uses of the park while anticipating the future needs of our community?

3) What would make Overton Park more financially sustainable?

These questions are not dissimilar to the ones asked by the Shelby Farms Conservancy and the Memphis River Parks Partnership, giving birth to plans that are nationally significant. It’s clear that the opportunity for Overton Park is just as bold.

A Historic Opportunity

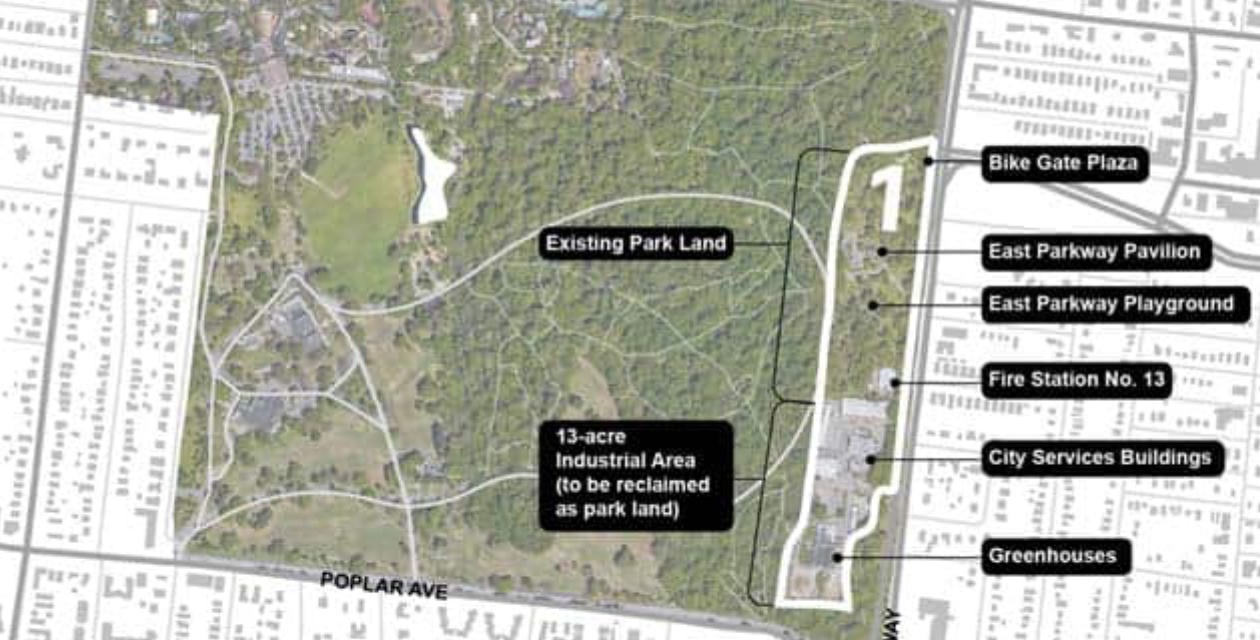

From the beginning of its master planning process, the Overton Park Conservancy has been serious about involving Memphians, offering ways to give advice, share recommendations, and lend their support. Its planning effort now focuses on what it calls Zone 1 — Bike Gate Plaza; the East Parkway playground, pavilion, and picnic areas; and the 13-acre tract on the site’s southeast corner now used by city government as a maintenance facility but to be returned to park use.

In particular, that acreage being returned to Overton Park makes Zone 1 the logical focus for the planning process at this point because once General Services Division leaves, the 13 acres will become a blank canvas on which a new portrait of this area can be painted.

Its future uses are limited only by Memphians’ imagination for it, and when the Conservancy says the public’s opinion is critical, it means it. It has kicked around some possibilities for the area but nothing has been decided and nothing is predetermined.

After decades of the public – and some officials inside City Hall – calling for a higher and better use of the maintenance area, the Strickland Administration has made it happen, overcoming the normal inertia and resistance it encountered from some in city government. For the first time in about 90 years, the public rather than government administrators will shape the decisions on the area’s future.

It means that for the first time in decades, a city administration has added land to Overton Park and is collaborating in a process to transform what is largely an eyesore today into a use that can become a glimpse into the future for Memphis’ first grand park.

Historic Context

That’s not to ignore the other assets on the park’s eastern edge as exemplified by the much-loved Bike Gate facing Sam Cooper Boulevard at East Parkway, picnics under the towering trees, kids in the playground, and more.

And yet, it’s hard for me not to concentrate on the maintenance facility because of how close the grit, grime, and squandered usage of these 13 acres came to be Overton Park as a whole. When I was a young newspaper reporter, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with “Citizens to Preserve Overton Park” and ruled March 3, 1971, that the U.S. Department of Transportation did not follow its own requirements that public parks could be used for highways only after it was proven there was no “feasible and prudent” alternative.

When the case was returned to federal court in Memphis, I covered it every day for weeks for three daily editions of the Memphis Press-Scimitar. Repeatedly, state transportation officials argued for the interstate highway to go through the park despite the devastating damage that would result. The path of the interstate highway – I-40 – would have roughly followed the old bus lane on the south side of the zoo and separate the park into two parts.

As the case was heard in district federal court by Judge Bailey Brown, state transportation officials continued construction of the interstate (now Sam Cooper Boulevard) directly at Overton Park. Remarkably, they then audaciously argued that the highway through the park made sense because of that new construction. In the end, the judge’s ruling in 1973 criticized transportation officials just enough to make it clear the roadbuilding was blocked and the future of Overton Park was preserved. And yet, it would by 1981 before the interstate was removed from state plans.

It’s easy to reflect on how close Memphis was to losing these 342 acres if the business community, Future Memphis, Chamber of Commerce, and other powers-that-be had been successful in carving up the park in the name of “progress.” It took a group of people who were demeaned and vilified as misguided to see the importance of Overton Park and to make sure its future was bright.

They were heavily criticized but no one is criticizing them these days. Their vision of what the park – and Memphis – symbolized what Memphis could be and it inspired a new park movement in the U.S. As a reminder, four years ago, it was spotlighted in a PBS special as one of the “10 Parks That Changed America,” because of the legal precedent it set in place.

Sound Off

Today, Overton Park has the same opportunity, and with the backing and counsel of the public, Overton Park can again symbolize Memphis’ aspirations and values as well as the park’s itself. The Memphis of today bears little resemblance to what it was when Lea’s Woods, to become Overton Park, was purchased by City of Memphis in 1901, and it is with an eye toward a future as an inclusive, diverse, and activated Overton Park that it can become a symbol for the new Memphis.

All of this is to say why you should care about this special park and have a voice in the planning.

The short survey on Zone 1 will produce preliminary concepts will be presented over the next three months.

Deadline for the survey is November 30.

Click here to take the Zone 1 survey.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.