Thumbnail: The decision about the relocation of the Confederate monument in Collierville’s most visible park on the town square will say volumes about its view of itself and be a preview of its future. So far, the mayor and board of aldermen have shown little political courage to be the kinds of leaders needed to unify their city.

**

Collierville

O little town of quiet streets

Oft in dreams I feel

Thy neighbors’ love and friendliness

Around my being steal;

Loved voices, scenes and faces

Linked in a golden chain

With Sabbath bells and sunshine,

And fragrant summer rain.

Time does not tarnish memories,

Years make them brighter grow

And through the rainbow of my tears

I greet old friends I know.

And laugh with them in poignant mirth

In the little town that gave me birth.

This poem, Collierville, was written about 1890 by the daughter of an early mayor of Collierville. It was a time when Collierville could be generously called a village. It was a time of “Grand Ball and Suppers,” community picnics, a bicycle club, cock fights, and horse racing, which were attended by all members of the town – who were white.

It was 20 years after the town – like Memphis – was reincorporated after losing its charter during the yellow fever epidemic of 1878. About that time, the Memphis Business Directory of Memphis, Tennessee and Other Towns described it as a progressive community with “a neat town square, upon which no expense has been spared to enhance its beauty.”

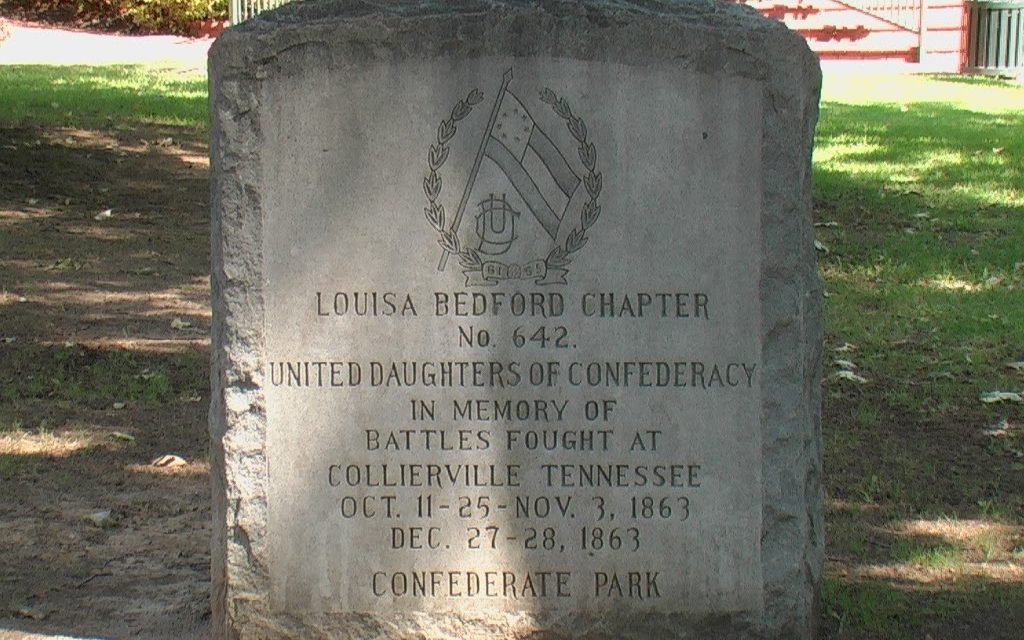

Confederate Park

That park in the center of town, described as “the public park” in early city deeds was named “Confederate Park” after the Civil War, according to the town history, but was more often referred to as “the park.” It was the only one in Collierville in those years, and it was home to peacocks, a deer, and a bandstand.

“in 1940, Collierville’s two United Daughters of the Confederacy chapters, the Louisa Bedford Chapter and the Maud Cowen Chapter, were instrumental in keeping, as Jefferson Davis put it, ‘the memory of our Southern heroes green,” according to the town’s history. “The inscription on the marker is a Confederate flag encircled by a three-quartered olive leaf wreath.

“At the bottom is the inscription – ‘Confederate Park.’ Also in July, 1941, the Mayor and board of Aldermen approved the construction of concrete walkways in the park that converged in the center of the summer house. The walkways were laid in the form of St. Andrew’s Cross like the one that appeared on the Confederate flag.”

As the poem suggests, the village saw itself as a place of gentility and Southern grace. That is, unless the residents were Black.

After all, as the 19th century drew to a close, it could not have been lost on any African Americans that they should stay in their place. Three lynchings in the Collierville area were potent reminders. Forty years later, they were reminded again when the monument was put in the park and even the sidewalks honored the Lost Cause.

Collierville bore resemblance to Maycomb in To Kill A Mockingbird. It too was small, “tired,” and racially segregated. Many citizens were old-fashioned, prejudiced, and proud of it, reluctant to change within a rigid class system which had Baptists at its bottom and Black people several rungs lower. The Southern social order captured in the town meant that no one crossed racial lines and it was possible for a white child growing up in Collierville until the late 1970s to never have contact with an African American child of the same age.

Schools were segregated, each race went to their own churches, and Black residents could only live in designated parts of town and were relegated to jobs of manual labor. They regularly weren’t called by their given names. Some were valued for jobs like bringing the shipments from the train depot, working as a maid, or delivering groceries. They were called “Uncle Tom” and “Shorty,” and in historic photos where white employees of a store were identified by name, they were listed as “others unknown.” In town histories and in the town newspaper, African American citizens were missing in action, because in fact, those only chronicled the lives and times of the white people of Collierville.

Context

In those years (when I graduated from my all-white high school, its population was around 3,000), it was impossible to imagine that Collierville would now be the 14th largest city in Tennessee with 51,040 people living there. The town grid I knew growing up was barely two square miles, but today, the town is a sprawling 30 square miles.

Today, Collierville is known for chaotic highway 72 leading into Collierville from the west, a route that features hundreds of restaurants and stores scattered haphazardly over the landscape because of the lack of a serious plan over the years to protect and enhance quality of life.

Notable in recent years is the increasing percentage of the population that is African American:

2000 – 7.18%

2010 – 10.85%

2019 – 12.4%

It is into this context that the debate about the Confederate monument in the park on the town square has taken on meaning. In a town committed to a veneer of harmony, pride, and equanimity, the Collierville Community Justice coalition – residents of the city – are willing to challenge the status quo, calling for the monument to be moved out of public space and to a place more appropriate.

The group’s agenda is broader than moving the monument. If it’s not moved, its members are asking for a sign contextualizing and denouncing the history celebrated by it and to create a plan to address racial inequities in Collierville.

While the mayor and board of aldermen appear committed to pretending if they ignore this, it will go away, they are wrong. The tide of history is sweeping over ugly reminders of the Confederacy and its defense of slavery and racism.

It is said that a city’s monuments reflect its core values, and this one suggests a city trapped by outdated, discredited historical events that have no relation to who it aspires to be today. After all, the values captured in this monument are about people who believed other people should be property, who were guilty of treason, and were committed to a resistance that, if successful, would have eliminated the United States.

In other words, leaving this monument in its most prominent place in the park says volumes about Collierville and its values.

Needed: Courage

At a recent meeting of the mayor and board of aldermen, Mayor Stan Joyner asked if board members wanted to discuss the monument’s location, and none of the aldermen responded, following the script to remain silent. Alderman John Worley, who is seeking reelection, said the “stance of the entire board” is to avoid taking action, which in this case, simply meant discussing it.

Unfortunately, most candidates for the board of aldermen are also content to aim for the lowest common denominator with old reliables like “heritage,” “outsiders,” and acting as if the four minor battles that took place at Collierville are somehow relevant today. Candidate Missy Marshall even falsely contended the park was never called Confederate Park, a fact contradicted by the town’s own written history, and managed to add the racist “all lives matter.”

Leave it to 21-year-old Gen Z William Lambert to give a definitive and logical idea, recommending its relocation to the Morton Museum of Collierville History where it can be contextualized.

The lack of courage – not to mention empathy – by most of the candidates may work in the short-term, but history is on the side of the coalition of Collierville residents calling for a park that welcomes every citizen of the town. While most candidates may consider their positions as clever politics, it is reasonable to question if their position is tantamount to admitting that they, if elected, do not plan to represent the 6,500 African Americans who live in Collierville.

How About A Reboot

As I’ve written before, the city’s history as it regards Black citizens is not as different from similar Southern towns as some of the powers-that-be would like to believe; however, hope springs eternal.

There was hope that Mayor Stan Joyner would show leadership, based on his advocacy three years ago to officially designate the park as the town square park to eliminate any idea that its name was Confederate Park.

However, that vote hardly matters. As long as the monument is present in the park, call the 1.33 acres what you will, but it will remain de facto Confederate Park.

Mr. Joyner probably doesn’t remember, but back when he was attending all-white Collierville High School, at the height of the civil rights movement, the all-white mayor and board of aldermen established the Human Relations Commission to advise it on racially charged issues. The Commission – chaired by the Episcopal minister with five Caucasian and five African American members – became a sounding board for controversial issues and forwarded its recommendations to the mayor and board.

Maybe it’s a good time for it to be revived.

The Choice

There is a tendency in Collierville, like many small Southern towns, to present an image of contentment. With about 70% of its workers commuting out of the city to work, town politics are often the focus of a vocal few, but this issue is not going away and eventually, Collierville’s elected officials will need to decide on whether it will be a city looking backward to a time when Collierville had 1,000 people and a white power structure that remained in place until the town’s modern history or look to the bright future that its leaders so often extol.

If the mayor and board of aldermen are unsure about what African Americans think about the monument, they can always ask their African American colleagues. Oh, that’s right; there aren’t any.

Put simply, there are probably 51,000 people living in Collierville today who were not living in Collierville when the monument was placed in the park, so the defense of the monument is not really about it. Rather, it’s about the kind of winner-loser brand of politics that divides cities where some white people cling to the past because they have somehow concluded that doing what’s right makes them look weak or that they have to resist anything that suggests Black folks are “winning.”

As Collierville moves ahead, here’s hoping the mayor and board of aldermen remember two things: 1) the coalition requesting the relocation of the monument is comprised of Collierville residents, not outsiders, and 2) dissent is the highest form of patriotism.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.