Thumbnail: City of Memphis has yet another magic number for the size of its police force. It continues the arrest and jail philosophy that has largely failed to develop a balanced crime-fighting plan that includes prevention and intervention. City Council is being asked to go on record in favor of a 2,800 police force but without the other critical elements to reducing crime.

**

So, now yet again, City of Memphis has another new number for how many police officers it thinks the city needs.

Spoiler alert: It’s going higher again. But then again, that’s really no surprise at this point.

Is enough ever enough? This time the number is 2,800 and the deadline for reaching it is by the end 2023. It’s not hard to imagine that by then there will be a new number, but more to the point what’s the financial note for 2,800 that tells the public how much this will cost, what share of the city’s budget that will then be spent for police, and how city government plans to fund other city services like libraries, community centers, parks, and the few safety net programs still left in city government. Keep in mind: the devastating impact of covid on city revenues will still be with us.

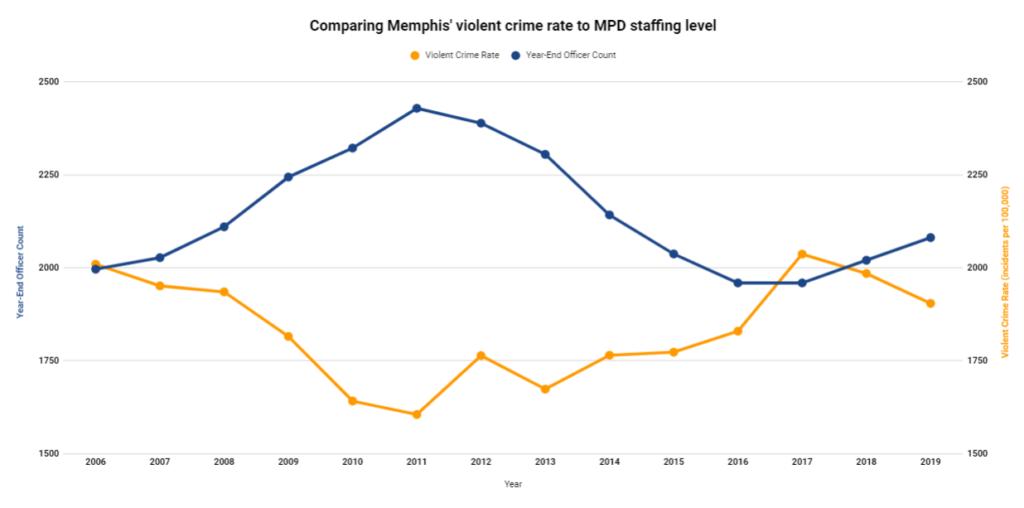

It’s a curious number because the charts emailed out by Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland would indicate that violent crime leveled off at a lower level of police officers, as indicated in 2016-2018 when the reduction in violent crime intersected with the number of officers. It would suggest that it would have been an optimal time to broaden crime prevention programs to include community-based solutions like intervention and prevention.

Just two years ago, Bill Gibbons, Crime Commission president, said the magic number was 2,300, and a year earlier, Memphis Police Department Director said it was 2,500. And now, Memphis City Council, acting on the mayor’s recommendation, is considering an endorsement of the latest number.

Watching the city’s behavior on the size of its police force is like watching a day trader obsessed on only one play rather than develop a balanced approach. When the market sumbles, he doubles down on the same play that got him where he is, in the hole.

Every year, the main thrust in attacking the crime rate is to do the same thing that was done last year and the year before and the year before. What’s missing is that while City of Memphis manages to swell MPD’s current budget by about $10 million in a year when Covid-19 has decimated revenues, it never seems to have enough money to add priorities like prevention and intervention.

What’s that they say about doing the same thing and expecting different results? The difference maker is not arresting and jailing more and more people rather but in unveiling a comprehensive, consistent, sustainable plan that attacks causes and not just results.

If Memphis City Council is intent on backing 2,800, it should only do so after requiring the administration to come back with a plan that is more than business as usual, one that includes all elements of crime prevention besides what former Shelby County Mayor and Sheriff Mark Luttrell used to call the easy one – suppression.

Other cities are reducing crime with a three-pronged plan of action, and in the absence of one, City of Memphis can’t arrest and jail its way out of crime.

Here’s a related post from February 18, 2020:

Crime Reduction: More Than The Size Of The Police Force

In the past seven years, there have been about half dozen studies that recommended ways that Memphis Police Department could be more efficient. Some suggestions were adopted. Many were ignored.

But at the heart of all of them has been the question: how many police officers should Memphis have?

The Marshall Project wrote a year ago: “According to several policing experts, cities are too focused on raw numbers, hiring consultant after consultant in a desperate quest to increase their headcount. A cottage industry of specialists caters to jurisdictions hunting for an optimal number of cops.”

Memphis “In Crisis”

To listen to the police union and to the director of police services, Memphis is in crisis because it needs more and more men and women in uniform on its streets. In the midst of these conversations, there’s the public perception that Memphis is unique to keep police on the force.

The number of police officers per 1,000 in population in the U.S. has been dropping for about two decades. Despite all predictions to the contrary, so did the crime rate. According to the FBI Statistical Brief on fulltime employees in law enforcement from 1997-2016, more than 23,000 of full-time sworn officers left departments across the U.S. About two-thirds of law enforcement agencies reported a decrease in applicants.

Meanwhile, the full-time sworn officers per 1,000 population dropped from 2.42 in 1997 to 2.17 in 2016. The crime rate fell 51% between 1993 and 2018.

These data are generally ignored by a majority of Americans – and likely Memphians. As the Pew Research Center wrote: “Public perceptions about crime in the U.S. often don’t align with the data…Americans believe crime is up nationally, even when the data shows it is down.” At the national level, about 60% of the public think crime is up. At a local level, according to Gallup polling, it’s lower with an average of around 40-45% believing that crime is up.

Other research has shown that the public’s perception of crime is driven by the media – think nightly TV news – and politicians.

Connecting Police Force To Crime Rate

Swelling the ranks of the Memphis Police Department seems like an obvious way to reduce crime, but research and policing experts are equivocal on the question of whether more officers necessarily drive down crime rates. As one said: It’s not how many you have, it’s what you’re doing with them.

And yet, Memphis’ conversation seems regularly to be stuck on how can we get more boots on the street.

“The Memphis Plan: A Strategic Fiscal and Management Plan for the City of Memphis, FY2014-FY208,” the 2013 report by The PFM Group and the consulting firm of former Memphis Chief Administrative Officer Rick Masson, said it this way: “The link between the number of police officers and crime rate reduction is, at best, elusive. Different studies have found different relationships and data suggest variation by city.

“Within Tennessee, Nashville achieved a 22.7% reduction in violent crime between 2006 and 2011 and slightly reduced its number of sworn officers per 100,000 residents. During this time, other cities decreased FTEs and sworn officers per 100,000 residents and achieved greater reductions in violent crime.”

In that context, the report recommended that Memphis better use non-commissioned officers so sworn officers can be deployed on more serious crimes.

No Lack Of Reports

Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland ran a “tough on crime” campaign in 2015, and in 2017, New York Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly, famous for his devotion to “stop and frisk,” was hired to give his recommendations to reduce crime. One of them was for Memphis to hire more consultants to determine how many police officers it needs by analyzing workloads, assessing the volume of 9-1-1 calls, and more.

Next up: the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) was hired, but it’s difficult to find the results of this report.

Meanwhile, Memphis Police Director Michael Rallings refers to another report when he pleads for more officers as part of his campaign to eliminate the residency requirement for MPD. Rarely mentioned is the issue of equity. As the Washington Post wrote: the share of white police officers in Memphis is higher than the share of whites living in those cities.

Consultant Alexander Weiss, reflecting on his work in New Orleans, told the Marshall Project: “When they say ‘we are short-handed,’ ‘we don’t have enough people,’ what they are really describing is a gap in their ability to staff according to their plan.”

To that end, Memphis Police Department should publicly post its plan and inventory all the recommendations of the past seven years to show which ones have been implemented

The Right Number

In a 2017 podcast with Just City, Mr. Rallings said MPD needs “exactly” 2,500 officers. He said 2,400 was “grossly under what we need.”

Earlier in 2017, Mr. Strickland had announced plans to increase the number of officers to 2,300 by 2020 but hesitated to say how many officers Memphis needs without further study.

In 2018, Bill Gibbons, president of the Memphis Shelby Crime Commission, said “there is pretty much a consensus that we need at least 2,300 officers.”

In October last year, Mr. Rallings said for Memphis Police Department to operate optimally, the department needs 2,600 officers.

In December, he said: “MPD is in a staffing crisis and our current staffing of 2,090 commissioned officers is significantly below those required for performance of our mission. Our goal is to have 2,300 commissioned officers by 2020.”

Needed: Debate

Today, Memphis has about 2,100 police officers, and Memphis Police Department continues to have the largest slice of the city budget – 38.3% – and its budget is more than every dollar of property tax brought in to city coffers by $14 million.

Former Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell often said that crimefighting is about more than the familiar “lock ‘em up” strategies. “Fighting crime is a three-legged stool,” he said. “Suppression is the easiest to do. The other two legs of the stool for fighting crime are prevention and intervention.”

Memphians have heard a great deal about hiring more police but it has never been converted into how much it will cost and what the plan is for paying for it without further depriving other services that affect crime – parks, libraries, community centers, and affordable housing – from having the money to accomplish what Mayor Luttrell called for – prevention and intervention.

More to the point, Memphis deserves a communitywide conversation and debate about crime prevention in general and about how to transform a public safety-starved city budget into one that can achieve the aspirations that Memphis has for its future.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.