Thumbnail: Racism can rear its head in the most mundane of situations for African Americans. Even a Memphis family in Destin is not immune from racist encounters. My memories of the Jim Crow South indicate how deeply engrained racism is in our culture.

**

A number of Memphis families, desperate for experiences other than those inside their own homes, have headed to Destin.

It included an upper middle class family from Cordova that packed up and headed for the beach for the Fourth of July holiday. They had all the paraphernalia for a relaxing day at the seaside.

It was a much-needed respite and it was going well until some men approached them and asked where they were from and similar questions.

The men were white and dressed in Trump swimwear. The family was African American.

Ever Vigilant

It illustrated yet again the realities of life as an African American. Whether driving through a neighborhood, walking through their own neighborhoods, jogging in public spaces, or participating in activities mundane and routine, African Americans can never completely relax their vigilance.

No matter how unexceptional the day may be, there is always the potential for it to turn on a dime. An unwelcome question, an objection to a Black Lives Matter sign, a traffic stop, a job interview.

African Americans know it can happen at anywhere at anytime.

Even on the beach.

It’s a sad commentary on the reservoir of racism that continues to influence so much of life in this country; however, with the national wave of support for Black Lives Matter, there is an opportunity today to leap forward in converting all those stirring words in the nation’s founding documents into a full reality of equal rights.

Engrained Racism

That doesn’t mean that it won’t come without the intense hostility of some white Americans clinging to the last vestiges of a class system in which they had prospered on the backs of people of color.

In the 1960s, in the midst of the civil rights movement, it was often said that things would be better when the older generation died. And yet, 50 years later, those of us of a certain age are the older generation that is the subject of similar comments today.

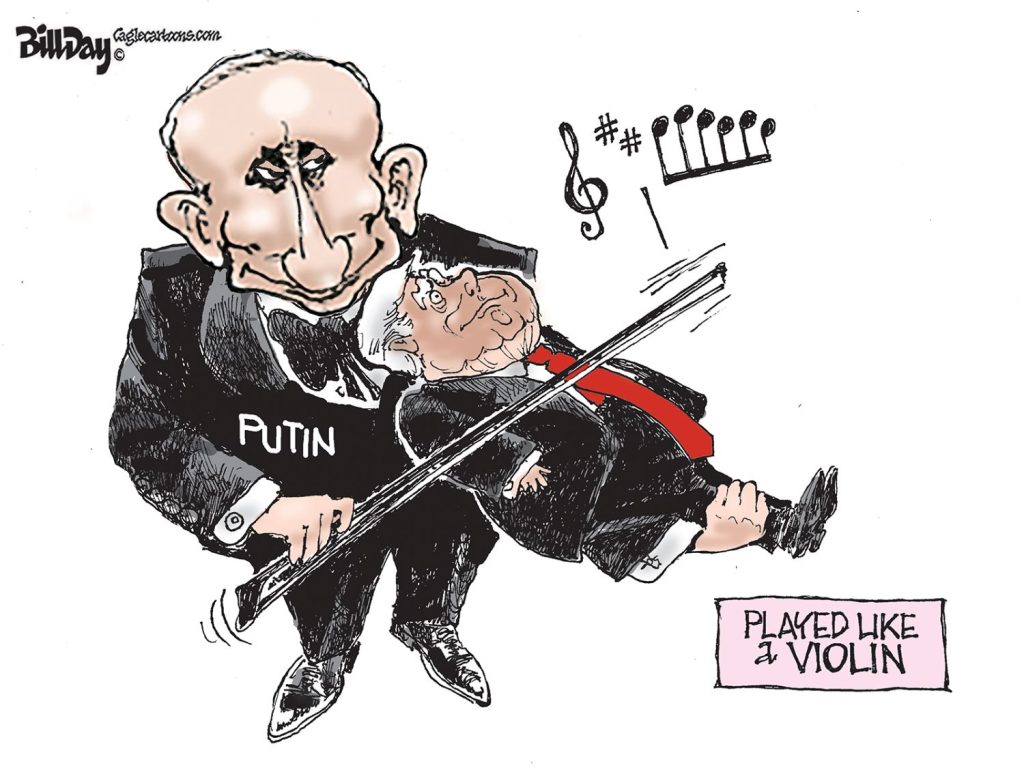

It is the sign of how deeply engrained is racism into the American psyche, and how hard some will battle to prevent it from being exorcised. That would be true at any time but with President Donald Trump basing his reelection campaign on racial division, hostility toward people of color, rejection of the Black Lives Matter movement, and dog whistles to the lowest forms of American ideologies rooted in hatred, white nationalism, and hegemony.

Hopefully, this is their last gasps.

In the face of a growing number of people who say: “I understand I will never understand, however, I stand,” there are some who will say they refuse to understand and never will.

There is so much that is accepted as just the way things are when they were choices made based on race and class. All of us can look back at things that now seem reprehensible and clearly racist, but at the moment in time, it was the ways things were.

Sundown Towns

I grew up in Collierville when it had fewer than 2,000 people. I never went to school with a Black student, we never competed with a sports team with a Black player, we never had a Black teacher, we never had a Black store clerk, and we never had a Black neighbor. The town square was named Confederate Park and featured monuments to the Lost Cause.

About 10% of the Collierville population were African American and it was rare that the two worlds converged. African American families were confined to specific parts of town. They were allowed mostly to hold jobs as laborers or domestic help.

It was the Jim Crow South. It was the Jim Crow caste system.

At the height of the civil rights movement, it was possible to find towns all over the South like Collierville, where people could remain in their own cocoons of discrimination and bigotry. Notable were the sundown towns which forbid African Americans from residing, or even visiting. Some famous ones in Mississippi even underscored their racism with large signs: “N——, Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On You In Our Town.”

However, across the United States, there were about 10,000 sundown towns. Even more had curfews that applied only to African Americans. It was what made the Negro Motorist Green Book an indispensable resource for Black travelers.

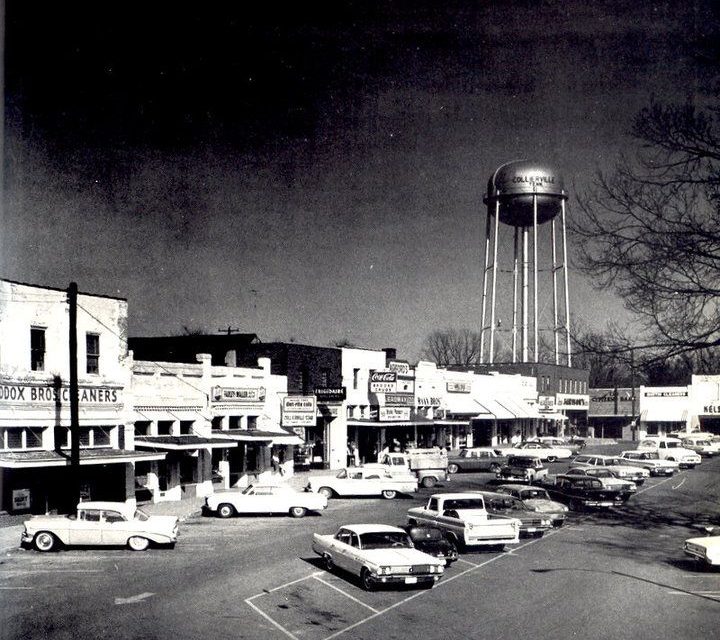

Old Collierville

Curfews were a frequently used cudgel against African Americans and even in small towns like Collierville which prided itself on its civility and good manners. And yet, well into the late 1960s, it maintained a curfew on the town square, which meant that African Americans had to leave the square when stores closed on Saturday night (although I can’t recall any African Americans on the square on any other nights either). Teenagers like me – the pivotal factor that I was white- could hang out on the square until we simply got tired and went home. It was such a fact of life that it was rarely questioned – at least on the white side of the color line.

When Rev. Frank McRae was named minister of the Collierville United Methodist Church, he asked inconvenient questions about equal rights but by and large, he was treated as a curious aberration. He would later become active in the sanitation strike in Memphis.

He was a largely influential influence on my life. He often laughed and said we radicalized each other. When a group of protesters visited the stores on the square in 1966 with the intention to integrate their bathrooms which bore new “Out of Order” signs, he spoke in defense of them, which led me to integrate the bathroom in the drug store where I worked. I was fired which gave us more time to spend together, listening to civil rights and protest songs.

I once saw an elderly Black man knocked off the sidewalk leading to the square because he did not step aside when the white man approached. Such racist behavior was explained away in Collierville because the white man did not live inside Collierville, farmed nearby, and came in for supplies. In other words, no “real” Collierville resident would do such a thing although the condemnation in the repeated stories about the incident seemed to be focused on the way it disrupted life on the square rather than the act itself.

Today, Collierville’s population is 51,000 and 12.4% of its population is African Americans, part of the middle class migration that drew middle class families to the city to get more house for the money (median house cost is $21,000 less). Most of the workers commute to Memphis to work, and while self-perceptions are still about its charm, courtesy, and neighborliness, it’s hard to imagine a Black Lives Matter rally held there.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.