And then life intervened.

It seems that most of us have a moment when our best laid plans take an unexpected path. That certainly applies to Bishop Phoebe A. Roaf’s first year as head of the West Tennessee diocese.

**

All of Rt. Rev. Phoebe A. Roaf’s life had prepared her for the moment a year ago when she was consecrated and ordained as the Bishop of the West Tennessee Diocese for the Episcopal Church.

Growing up 144 miles southwest of Memphis in the Arkansas Delta city of Pine Bluff, she knows the struggles and the potential of this part of the U.S. Trips for shopping and entertainment brought her to Memphis on occasion. She received a law degree from the University of Arkansas – Little Rock, clerked for two years for a federal Court of Appeals judge, and worked in a New Orleans firm from 2000 to 2005.

By her early 40s, she had come to understand that her life’s calling was not the law. Rather, it was to serve as a member of the clergy in the Episcopal Church. Armed with her bachelor’s degree from Harvard University and an MPA from Princeton University, she attended Virginia Theological Seminary, the flagship seminary for the Episcopal Church, graduating in 2008 and now serving as vice-chair of its board of trustees.

By 2011, her theological career had taken her from Trinity Episcopal Church in New Orleans, where she was associate rector, to become rector at Richmond’s St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, the oldest African American Episcopalian Church in the South.

The Journey to Memphis

A year ago, she became West Tennessee’s bishop in a journey that seemed divinely inspired, bringing her back to the area where her life began and where the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., an inspiration to her, ended.

On May 4, 2019, she was consecrated with the customary pomp and circumstance of such ritual events. And yet, the electricity of the day was traced to more than tradition. It was the long overdue shattering of Christian traditions reflecting the racial and gender divides of the South.

After all, as a girl, Bishop Roaf never saw a woman priest in the pulpit, much less an African American woman priest. And yet, today, she symbolizes the transition of the Episcopal Church to become a leading force within Christianity for a faith that calls for social justice and fair play.

As Bishop Roaf settled into her new responsibilities, she had an agenda for her first year, setting out her administrative priorities and a schedule to visit each of the 29 churches in the diocese by the first of June of this year.

And then life intervened.

A Time of Great Change

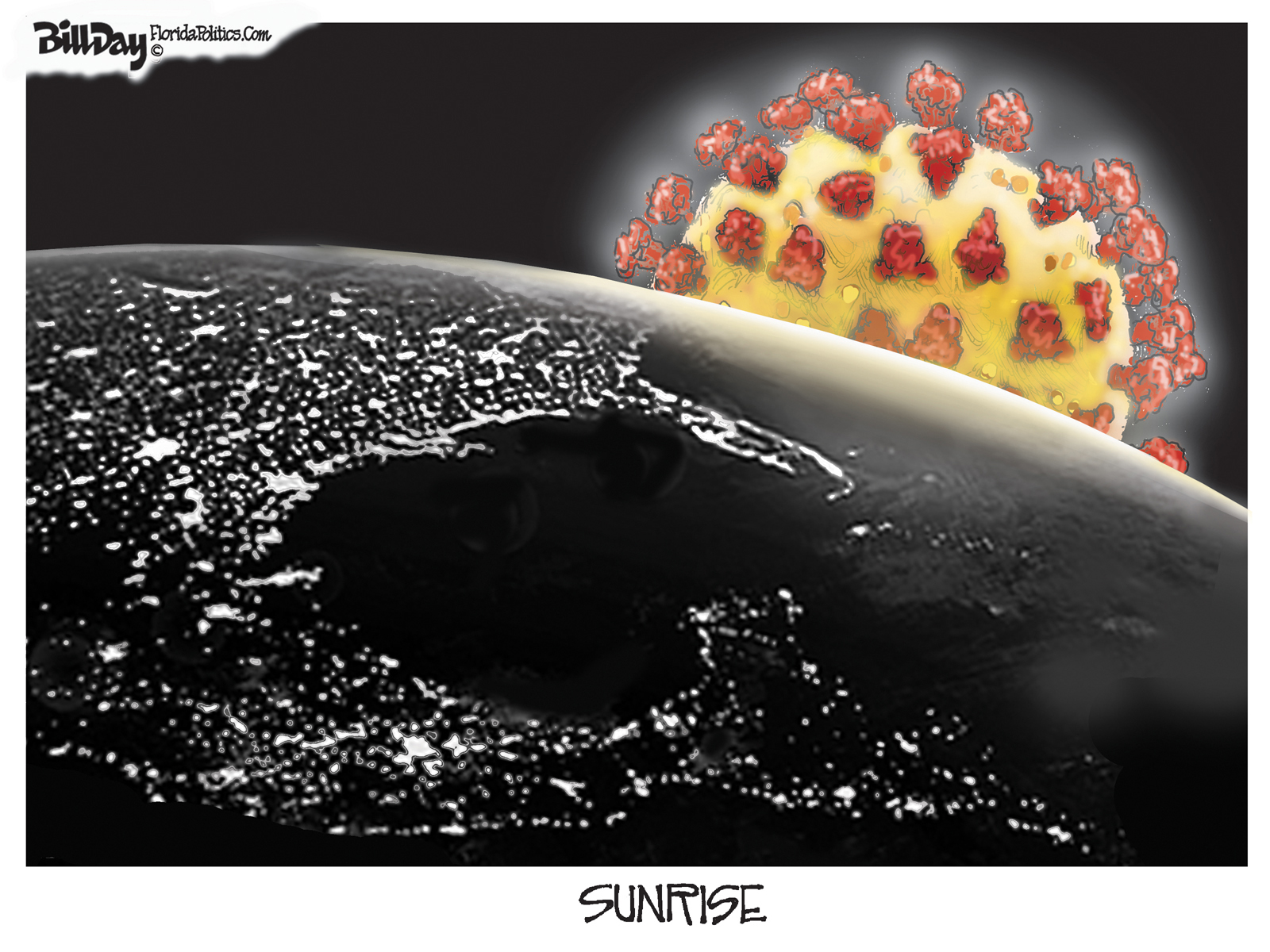

Covid-19 upended all the best laid plans, and the bishop’s attention turned to decisions about the close of in-person worship, exploring the most effective use of streamed services, and ways to maintain personal contact in a time of social distancing.

“It felt good to come back to his area after years on the East Coast,” the 56-year-old bishop said.

The West Tennessee diocese is a small one. Most dioceses have 80 to 100 congregations, but when Tennessee was divided into three dioceses in 1983, West Tennessee was given 29 churches with just over 8,000 members. Her plan was to visit each of the congregations by first of June, but Covid-19 upended the schedule.

And yet, she is serious about finding the silver lining in this pandemic cloud. “With all the technology we have today, if we cannot be present with each other, how do we use technology to be more efficient and to develop relationships?” she said, adding that employing technology in ways that enhance faith is not merely a challenge during the coronavirus but a harbinger of things to come as the Episcopal Church explores life in the digital world.

To emphasize the point, Bishop Roaf refers to The Great Emergence: How Christianity Is Changing and Why by widely beloved religious publishing legend Phyllis Legend, who lived in Lucy, Tennessee, outside Memphis and was the author of two dozen books, a lector, and lay eucharistic minister in the Episcopal Church. Her book made the persuasive case that Christianity undergoes massive change every 500 years, and that we are in the midst of such a time now.

Answering God’s Dream

“A number of faith communities had never done live streaming,” she said. “There is some resistance to technology within the context of worship, but we have more people showing up virtually than who came (in person) before. Some are not even members in the church or the diocese and some were outside the country. We’re having conversations about how do we maintain this presence in the digital world, particularly with young people, because if that’s where they are, that’s where the Church should be. The Church should facilitate conversations in social media, and how we can use social media in ways that rise the level of social discourse.

“In the South, there is a genteel veneer but underneath there is often hard-core delineation of roles and separation. So, we should be the place to figure out how to get along and use our gifts and skills to figure this out. God’s dream is to bring people together. When we can come together for God’s agenda, that is God’s dream. Sunday morning is still the most segregated time of the week. What role does the church have in wanting people to have a living wage? Who is at the table speaking for the least, the lost, and the lonely?”

In the midst of the shelter-in-place months, Bishop Roaf said churches have returned to “old-fashioned practices” like telephone calls, sending snail mail, and telephone trees while adding Zoom coffee hours or church members staying on Zoom an hour after digital services to talk and share.

Today, she and the diocese’s priests are planning for a reopening of sanctuary worship for the first Sunday in June. There will be social distancing and people will be encouraged to wear masks, there will be no Sunday school or nursery, and there will be morning prayer rather than the Eucharist.

The time since the pandemic closed Episcopal Church has been a trying time for Bishop Roaf like it has for all of us. It disrupted plans, it complicated lines of communications, and it resulted in the longest period of time in which she has not taken the Eucharist.

Running The Relay

She is fueled by the energy she’s found in Memphis and her participation in the convening by Church Health Center founder Scott Morris of interfaith leaders – Jewish, Muslim, and Christian – to address coronavirus and look to the future.

She said: “Whatever time the Lord has for me here, it’s a relay, not a sprint, and I will hand off the baton at some point. It’s not all on me, but can I in some small way contribute?”

In confronting the challenges of Covid-19, she is comforted by the thought that “this too will pass,” and to keep things in perspective. “We’ve been through major crises in human history, and she said the question is what can we learn and how can we be better” as a church.

Her inspiration for pressing on and acting on her faith is found only a short walk from her office. There, on the high altar at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, are the names of the “Martyrs of Memphis” who gave up their lives to serve, minister, and care for yellow fever victims in 1878.

There has never been a bleaker time in the history of Memphis. More than half of the population had fled the city in panic, stores were boarded up, shops were shut down, and there was an unsettling silence. People dropped dead in the street, bodies were found in parks and public places, and a newspaper put it simply: “We are doomed.”

Finding Inspiration

In the midst of the gloom, Episcopal nuns who came to be known as “Sister Constance and her Companions” – three other nuns and two priests – refused to leave and instead served Memphis from the plain wood church on Poplar Avenue that was then St. Mary’s Cathedral.

In today’s cathedral, the altar bears the names of the sisters, and they are also honored in a brass wall plaque and a stained glass window. The “companions” are buried together in Elmwood Cemetery.

Bishop Roaf said saints are ordinary people inspired to do extraordinary things. “I think of these nuns who went through really challenging times,” she said. “I don’t want anybody to be a martyr, but I ask myself, ‘Can I hold to their values of compassion and hospitality?’ They tended to the sick from all walks of life and were powerful witnesses.’”

It’s easy to imagine that Bishop Roaf also finds inspiration from within her own family. Her father was a dentist and prominent in equal rights in education programs in Pine Bluff. Her mother was the first African American woman on the Arkansas Supreme Court. She has three siblings, including NFL Hall of Famer Willie Roaf.

In a family known for setting milestones, she’s recognized as one of the Episcopal Church’s bright lights. That light now shines in Memphis toward a bright future for the West Tennessee diocese.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis