Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris’ proposal to provide almost $10 million for Memphis Area Transit Authority is an important step toward a better future that recognizes the impact of public transit to a successful community.

In its way, his idea for charging a special fee for people who own three or more cars was in its way “congestion pricing light.” It is of course built on the assumption that car ownership is a proxy for family financial strength. That said, $145 a year for each car above two needs justification since that is more than the owner paid for that vehicle’s license and associated taxes.

Cities around the world are considering how to tax people who produce more congested streets in order to address traffic congestion, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and create a more equitable transportation system.

More than a dozen cities around the world have already imposed congestion pricing, and it appears that Seattle will be added to that number in the near future.

There, the city’s department of transportation said it well: “Helping our working families and the communities historically underserved by our transit system will be critical as Seattle studies how to mitigate growing congestion. As we continue to explore congestion pricing in Seattle, our intent is to advance equitable outcomes through community engagement that will guide the development of a fair pricing program.”

The Case for Transit is Clear

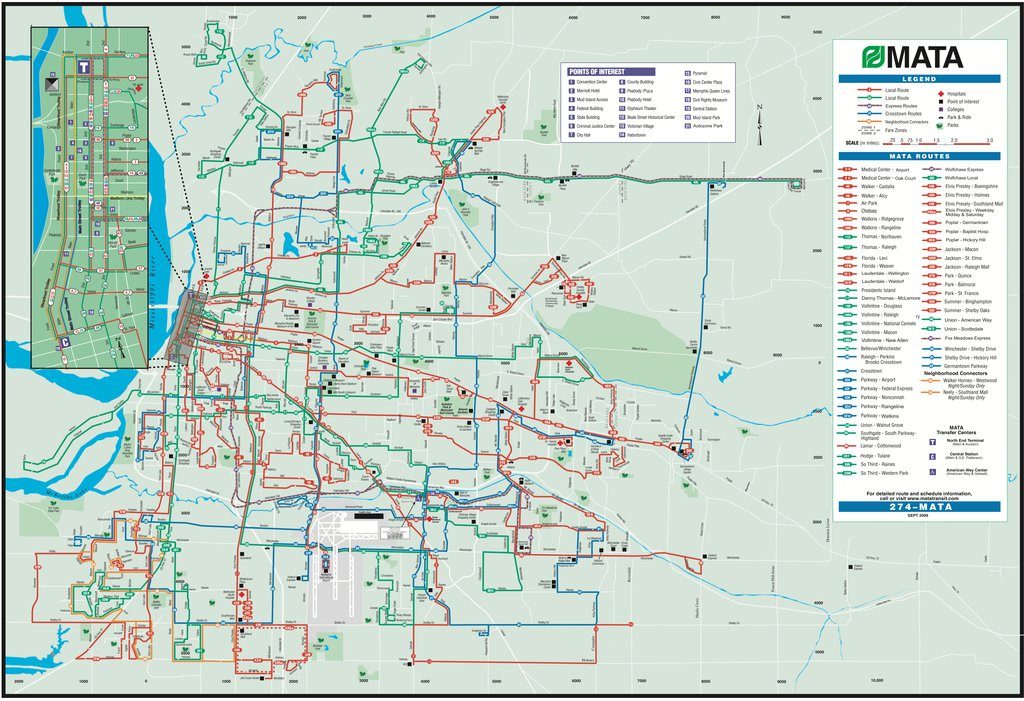

That same laudable motivation seems to lie at the heart of Mayor Harris’ plan to help fund MATA, which has a proven need of $30 million in additional funding if it is to upgrade services to a level commensurate with cities we often list as our “peer cities.” The need is underscored by the fact that 0% of households making less than $50,000 are within one-half mile of high frequency full-day transit.

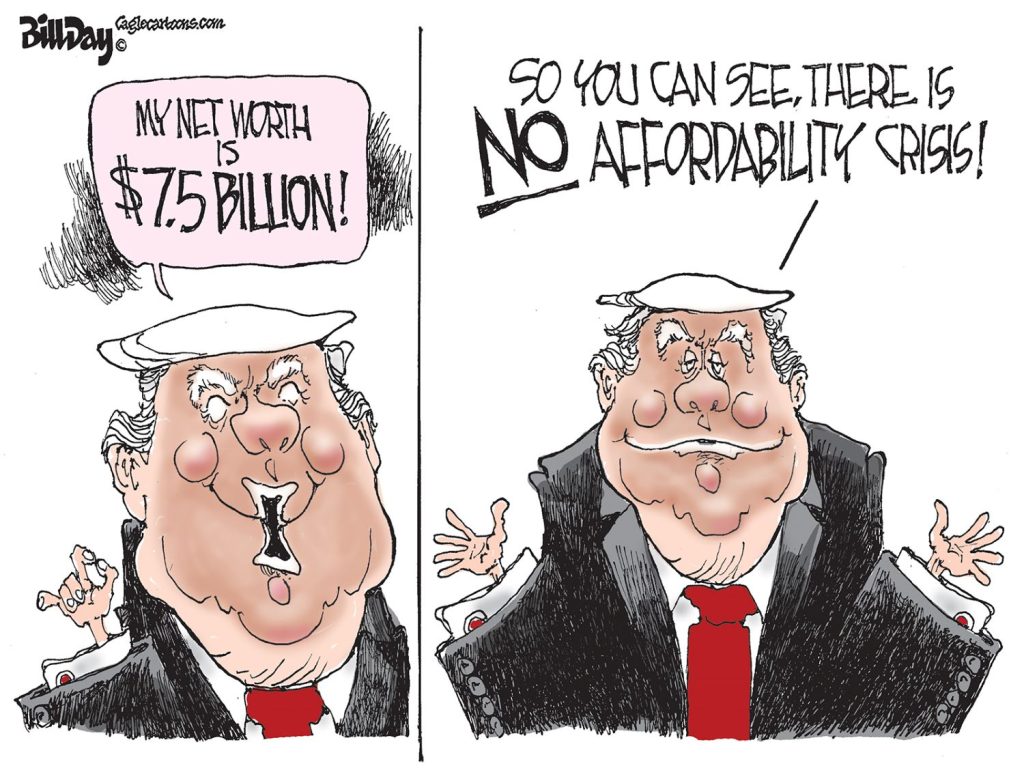

There are many reasons that all of us should, in our own enlightened self-interest, support more funding for MATA, but chief among them is that the lack of an effective system forces Memphis families to buy a car, despite the fact that many of these families have many better uses for this money. Meanwhile, the Memphis region is #1 in the percentage of median income spent on transportation – 27.8%.

It’s no wonder that a 2015 study by Harvard University found that access to transportation is the single biggest factor in the odds of escaping poverty and avoiding homelessness. A 2014 study by New York University found a link between poor public transit access and higher rates of unemployment and lower incomes in New York City.

Here, the lack of high frequency public transit means that car ownership is a necessity for many families, draining money from their budgets that could otherwise be spent on food, after school programs, and more. In this way, a high-performing public transit system frees up disposable income that can act as an incremental step in an overall plan to create better paying jobs and closing the income gap between whites and people of color.

Tax Equity

Truth be told, public transit should be part of county government since it has the broadest tax base. Roughly speaking, the $30 million in city funding for MATA amounts to about 25 cents on the city property tax rate. In county government, that would amount to about 15 cents on the property tax rate.

Or put another way, if Shelby County allocated 40 cents on its tax rate for MATA, it would generate more than $60 million a year.

But that’s likely just wishful thinking. Such rationality in the definition of what is a municipal service and what is a regional (Shelby County) service has been lacking for decades. To its credit, Memphis City Council forced some logic into the funding responsibilities when it stopped funding some joint city-county services.

After all, at its peak, Memphians were paying about 80 cents of every dollar in the budget of these joint agencies – 100% of the city funding and 65% of the county’s funding.

Selection Concern

That lack of fairness never managed to hit the radar of Republican county commissioners when they had a majority, so City Council members had little choice if they were to eliminate the double taxation of Memphians.

And yet, in the wake of Mayor Harris’ proposal, the county commissioner from Millington, Amber Mills, immediately complained that MATA does not now have a route to the North Shelby County city (not that she suggested higher funding from county government to make that happen).

Then, too, if Millington wants bus service, it can do the same thing that Memphis does – pay for it.

Her comment also presupposed that the majority of people who own three cars living in the suburbs and they “will be footing the bill.”

A Case Study in Equity

Actually, targeted people with three cars for the new fee is nothing less than progressive taxation.

Just once, it would be refreshing if one of the politicians concerned about people of means paying their fair share in taxes for public services would be concerned about our regressive tax system.

You see, in Tennessee, the lower your income, the greater percentage you pay in taxes. It is the quintessence of regressive taxation, one that is upside down and punishes poorer families while protecting the wealth of higher income families.

Leo Arnoult, member of the MICAH (Memphis Interfaith Coalition for Action and Hope) transit task force, said his group is “guardedly optimistic that this meets our criteria of equity.” On its face, the Harris proposal is a case study in equity and deserves approval by the county commissioners.

None of this will happen overnight. Because the fee has to be approved as an ordinance, there will be three separate votes by the commissioners and Mayor Harris is hoping for a vote by February.

A Step Ahead

As part of the Blueprint for Prosperity plan to reduce poverty by 10 points in 10 years, 15 University of Memphis professors focused on key issues in a comprehensive research-based report and a compendium of recommendations issued in 2015.

Dr. Charles Santo, chair of city and regional planning, wrote the report on transportation. One strategy was “to make transportation planning central to the city and region’s economic development planning. Current planning is driven by moving goods and packages, not people. That means roads are designed to get goods into and out of the city. But little attention in planning or funding is given to moving people and particularly in moving people from their homes to jobs. Future planning should focus on connecting households to jobs by reducing travel times between the urban core and area job centers.”

As he pointed out, the “story of the transportation-poverty relationship is the story of urban form, geographic stratification, and spatial inefficiency, and it is conditioned by the geographic size of the city, historical patterns of population and wealth decentralizations, and the industrial structure of the local economy.”

In other words, we have no shortage of smart, informed suggestions for how to proceed, but all of them require us to take off the blinders and consider how we can take actions that aren’t aimed at “fixing” MATA but ultimately are aimed at creating a regional transit system that becomes a competitive advantage for expanding our economy, moving more people into the middle class, and keeping more talented workers.

Mayor Harris took an important step in that direction with his MATA proposal, but it is a long way from being a done deal because the pushback on an additional $145 a year fee promises to be aggressive.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

`

I think you need me to produce a video explaining exactly how the car fees work to the public if you want to combat negativism from the start.For example,many parents still hold the titles on their children’s cars but that doesn’t mean the parents own multiple cars. Those “children may hold down jobs & attend school – needing those cars. MATA can’t provide 24/7 to every location at all times. I’m sure there are other “exceptions” to the rule as well.

Good article! Residents of Shelby County (of which I’m one) should view MATA as OUR mass transit system and, like the article pointed out, fund it on a level consistent with other metro systems. It’s important the residents of Shelby County have a ‘good’ mass transit system for many reasons. But one of the most important ones for Shelby County is that there are many residents who are poor and have a hard time getting around. Congestion isn’t so much a reason here – yet. Also, most metro transit agencies are funded by the county, or counties, which they serve. And these agencies are usually funded by some sort of dedicated source, like a percentage of a sales tax or of a gas tax, or the like. This is the model residents of Shelby County should ultimately be aiming for. At the least, it’s good news to hear that Shelby County government is finally – in the year 2019! – starting to view mass transit as an important county amenity and as an important part of county infrastructure, and worthy of investment.

An improved transit system is needed; but this is not the right solution. First of all this will do more harm to Shelby County and likely result in the loss of more than 9 million revenue it is to bring in a year as this could spur an outflow of sales and property tax dollars to surrounding counties who will not be subject to this funding source. Many residents will just decide to move out of Shelby County or relocate their businesses (and their fleet of vehicles) elsewhere. A bus system alone primarily within the city will also be hard for others to justify. If rail transit from Downtown stretching east and south along the Poplar Corridor and to the MEM International Airport can be included along with a tax on those who come into Shelby County to work and clog our highways and city streets then it might be easier to swallow.

An improved transit system is needed; but this is not the right solution. In fact, the solution is horrible. First of all this will do more harm to Shelby County and likely result in the loss of more than 9 million revenue it is to bring in a year as this could spur an outflow of sales and property tax dollars to surrounding counties who will not be subject to this funding source. Many residents will just decide to move out of Shelby County or relocate their businesses (and their fleet of vehicles) elsewhere. A bus system alone primarily within the city will also be hard for others to justify. If rail transit from Downtown stretching east and south along the Poplar Corridor and to the MEM International Airport can be included along with a tax on those who come into Shelby County to work and clog our highways and city streets then it might be easier to swallow.

The Mayor is trying to thread a needle and do the right thing. Raise the property tax and get it done. Leo has been a big help as well.

I fully support the County funding MATA, but I too have a lot of questions about the mechanism. I am one of those people that have 2 children still living at home and going to college and jobs. Why should I pay and extra $290?

I can also say that their are at least 6 households on my North Memphis block that have more than 2 cars (and more than 2 generations) living at the same house.

What about tradesmen that may have two passenger cars and one or more work trucks?

What is to stop people from doing what used to be done during vehicle inspection days, and registering vehicles outside of the county? When is comes to commercial fleets, don’t many companies also own property outside of the county that they would switch their registrations too? Could this cause fleet operating companies to flee Memphis to North MS?

just askin’