In truth, celebrating Memphis’ 200th anniversary this year is largely ceremonial, ignoring earlier settlers and forgetting that the city was the first city west of the Alleghenies to be a planned community.

It was the earliest version of Memphis comprehensive planning – think Memphis 1.0.

By 1819, the date celebrated as the founding of Memphis in this year’s bicentennial, there were of course people already living in the rough wilderness encampment that was to be named Memphis by developers Andrew Jackson, Marcus Winchester, and John Overton.

However, by the time the first lots in Memphis were sold in 1819, explorers had been criss-crossing the area for several centuries. A fort had been built by the French in the area in 1739, almost 60 years after they claimed the territory for their country. In 1795, the Spanish built their own fort and that was followed by an American fort in 1800-1803 which remained an army outpost until about 1812.

Memphis 1.0

The development scheme for a new city had been around since the 1790s when John Rice obtained a 5,000-acre grant that included a riverfront essentially as it is today but with a tongue of land separating the Mississippi and Wolf Rivers in front of the bluff where the town would be laid out. In 1783, the rivers met near what is today is the foot of Jefferson Avenue, and the Mississippi’s current struck the bluff at what was to become Union Avenue. By 1819, the mouth of the Wolf River had retreated to today’s Auction Avenue as a result of Mississippi River erosion.

John Overton purchased the land from Rice’s brother (Rice had been killed in a battle with native Americans) and sold half interest to Andrew Jackson, a frequent investment partner. General James Winchester joined their partnership later and is generally credited with bestowing the Egyptian namesake on the new town (although it would often be referred to as Chickasaw Bluffs in media accounts).

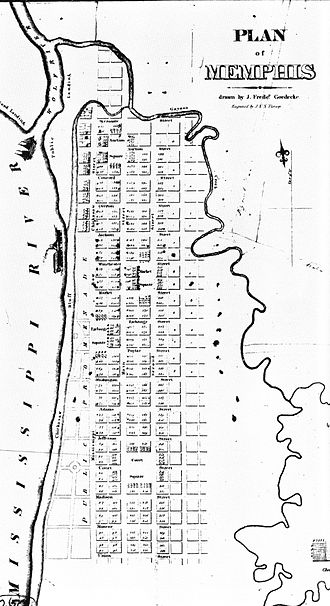

On January 12, 1819, the three inveterate land speculators agreed to lay out a town site and hired surveyor Williams Lawrence to do it. His finished product was a rectangular town site containing 362 lots, laying parallel with the riverfront. None of the three developers planned to live in Memphis so Winchester’s son, Marcus, was sent to act as their sales agent.

The romanticized version goes like this: In 1819, Memphis was founded by Jackson, Overton, and Winchester, who, standing on the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff of the Mississippi River and looking at the untamed river and wilderness, foresaw a city of greatness. They named it Memphis after the legendary capital of Egypt located on another great river, the Nile.

The story is apocryphal. The three prominent Middle Tennesseeans never visited Memphis at the same time. Indeed, Jackson, if he visited at all, may have only visited the city briefly three years after its founding on his way to become governor of Florida, and Overton did not travel to assess his investment for months after its founding. This was not for lack of interest because their correspondence about Memphis was frequent, but because the journey from Nashville to Memphis was arduous and circuitous with the most preferred route being 287 miles.

Smart Growth

We’ve always found the back story interesting, but it brings us to our point: in 1819, city planning was of little concern west of the Alleghenies, and yet, Memphis was one of the best planned towns of its day.

The founders’ vision of a great city was captured in a plan that laid out its streets in a classic grid punctuated by four squares – Court, Auction, Exchange, and Market – with a public landing at Auction Street on the Mississippi River to attract river commerce and a promenade on the bluff set aside for public purpose. At the time, surveyor Lawrence wrote that only three non-native Americans lived at the site and there were no roads and only two “Indian trails” leading to the bluffs.

In other words, the street grid was a tremendous exercise in faith. The date we celebrate as the day Memphis became a city, May 22, 1819, was the first day that the lots were sold and certificates of title were issued.

What is striking is how this original grid has stood the test of time. It was as Memphis grew that the grid broke down as streets widened to the point that by the last half of the 20th century, engineers routinely overdesigned streets swelling frequently to six lanes.

Maximizing The Benefits

The wisdom implicit in the historic grid is underscored today by the fact that most of it has capacities that can still handle traffic counts much larger than they see today.

As we mentioned last week, Third Street/B.B. King, Second Street, and Front Street have average daily capacities of 24,000 vehicles, but their traffic counts are respectively 7,985; 5,807; and 7,494. Meanwhile, Riverside Drive has an average of 13,000 vehicles a day on a road which has a capacity of 20,000 vehicles if it were two lanes.

Compared to the 2007 traffic counts, most of the historic grid falls far below capacity, which suggests to us that while Downtown Memphis Commission is studying parking needs and future demands, it would be timely to consider how the historic grid can be used more effectively. After all, the Memphis historic grid maximizes choice, disperses traffic, and increases density while new streets minimize choice, concentrate traffic, and reduce density.

All of this requires Memphis to adapt to a more realistic definition of congestion. We tend to think that traffic should never be backed up, whether it is 5 p.m. on a weekday or after a FedExForum basketball game. And yet, when we travel to other cities, we don’t have the same expectations and we consider backed up traffic the evidence of living in a major league city.

Words To Live By

If traffic engineers were laying out downtown Memphis today, they would likely make it twice as large as it is to handle the same amount of traffic. Probably until about 1950, a street grid for transportation and development was used in Memphis, but about that time, it disappeared almost overnight as the city flipped its priorities and made cars first and people second.

With this new emphasis, more lanes appeared while street life disappeared along with community spirit, cohesion, and vibrancy.

Finally, with the end of the 20th century and the dawn of a new one, new urbanists called attention to the power of the traditional grid in building high functioning cities, but it’s not been possible to make the degree of changes that are needed because of the entrenched power and rigid thinking of traffic engineers.

As Jeff Speck, urban planner and author, famously said in his 2008 Memphis presentation: “Don’t leave the design of your city to the highway engineers.”

Walkable Urbanism

Unfortunately, transportation planning is entrenched in the same thinking that brought us streets that encouraged sprawl and discouraged greater density, and even after half a century, there is still resistance to consider changing from the newer, fragmenting street networks.

We’ve now seen that there is a better way. Madison Avenue is an incontrovertible proof point and similar complete street projects in other parts of Memphis only emphasize the point.

The best news of all is that there is a growing constituency demanding to treat streets as the public spaces they are. As traffic engineer Walter Kulash, well-known here for his advocacy for a smarter context sensitive design for Kirby Parkway through Shelby Farms Park, said that the better choice is the one offered by well-connected street networks that lead to more capacity and efficiency.

Back in 1990, always ahead of his time, Mr. Kulash was the first to promote walkable urbanism as an alternative to conventional suburban development. His main point is widely accepted today, and can be seen as a thread in the Memphis 3.0 comprehensive plan: complete streets are fairer and more positive for cities, diverting traffic to other modes such as walking, bicycling, and transit and freeing up street capacity. At the same time, complete streets are also safer.

The Pressing Question

Implicit in his thinking is that traffic must be slowed to make streets comfortable for people who aren’t in cars because in walkable neighborhoods, the street grid gives everyone more choices.

It may be called new urbanism, but this is urbanism as historic as the downtown street grid.

As Mr. Kulash put it: “The fundamental reason why a dense network of small streets outperforms a sparse hierarchy of streets is that streets become less (not more) efficient as their size increases. So instead of an efficiency of scale as the street gets larger, we experience instead a deficiency of scale.”

A new handbook from the Institute of Transportation Engineers, Implementing Context Sensitive Design on Multimodal Thoroughfares, is a sign of hope. It offers advice on the connectivity of street networks and that dense grids are safer and more positive forces in a city.

The historic Memphis street grid is already our most convincing evidence and raises the obvious question of why aren’t we building more like it.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.