By Joe Cortright

The case for using tax increment financing for affordable housing in gentrifying neighborhoods

The problem with gentrification is that rising property values may make it expensive or impossible for lower and moderate income residents to live in an area. But what if we could tap some of that increase in land values to subsidize affordable housing in affected neighborhoods? We can, and that’s exactly what Portland has done for more than a decade: It now sets aside 40 percent of the tax increment funds (TIF) raised in urban renewal districts. Since 2006, the program has generated nearly a quarter of a billion dollars to support affordable housing.

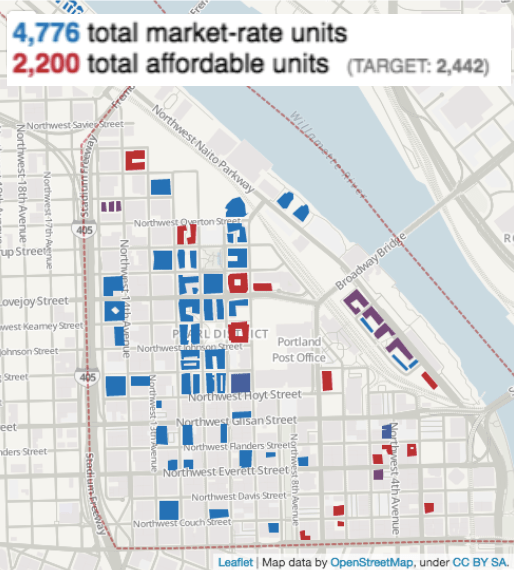

And there’s little question that it has supported income diversity in redeveloping neighborhoods. Portland’s tony Pearl District, adjacent to downtown, as blossomed in the past decade, adding more than 7,000 new residential units, plus offices and stores. The city’s policy has plowed tens of millions of dollars in the tax increment from new construction and rising property values into affordable housing in the neighborhood. That funding, coupled with other resources, has supported the construction of 2,200 units of affordable housing, interspersed with market rate units. Elsewhere in the city, urban renewal funds are being used to support the construction of affordable apartments and subsidize a homeownership program, with funding targeted to helping residents displaced in previous decades.

Using TIF to support affordable housing is a key policy for minimizing the effects of neighborhood revitalization. It taps the increase in property values associated with gentrification, and spends that money on building additional affordable housing, and thanks to the geographic nature of TIF districts, puts the funding in exactly the places where development pressure is greatest. In addition, TIF funding is automatically proportional to need: the more property values rise, the more development occurs, the more money TIF generates for housing.

And unlike inclusionary housing requirements that drive up the cost of development, and load costs solely on new residential units–which have the effect of restricting supply, and likely worsening affordability problems, TIF doesn’t change the development cost calculus for new housing construction.

Why use TIF for affordable housing in gentrifying neighborhoods?

Urban revitalization projects have the effect of driving up property values, and resulting in increased market rents, which creates justifiable concerns about housing affordability and potential displacement. If cities can harness some of the increase in market value, they may be able to generate resources to subsidize the preservation, rehabilitation or construction of affordable housing, and ameliorate these effects.

Lance Freeman of Columbia University, one of the nation’s leading scholars on gentrification, has suggested using tax increment financing to subsidize affordable housing in neighborhoods experiencing rapid change. He wrote:

“Financing could come from the increase in property values and consequently property taxes in the zone that by definition accompanies gentrification of the type that might cause displacement. The increase in property taxes in the gentrifying neighborhood could be set aside specifically to fund affordable housing in the very neighborhood undergoing gentrification.”

One of the biggest problems associated with affordable housing is achieving scale. While community land trusts and inclusionary zoning requirements are often touted as solutions to gentrification, they are seldom able to produce many units of housing in a timely fashion. For example, New York’s inclusionary housing program produced fewer than 200 units per year in all five boroughs combined; in the Pearl District alone, Portland’s Portland’s TIF program supported more than that number in the Pearl alone in the same time period.

A key advantage of harnessing TIF is that it supports mixed income neighborhoods. TIF financing is geographically limited to redeveloping neighobrhoods assuring that low and moderate income housing gets built in the same areas that are experiencing new market rate housing construction, automatically precluding the establishment of purely high income enclaves.

Portland’s TIF for affordable housing program

Portland Oregon dedicates approximately 40 percent of its tax increment financing (TIF) revenues to subsidizing affordable housing in urban renewal areas. In the past eight years, the program has generated nearly a quarter of billion dollars for affordable housing, and helped support the construction and rehabilitation of thousands of units of affordable housing. The program provides affordable housing in neighborhoods undergoing revitalization, and does so without creating dis-incentives to private market housing.

For the past decade, Portland has dedicated a portion of the revenue from its tax increment financing to help underwrite the cost of constructing new affordable housing. This program applies in the city’s designated urban renewal areas, which by statute are restricted to include not more than 15 percent of the city’s land area.

This program has evolved over time. Originally, it was applied to a single urban renewal district (the River District, which encompasses the Pearl District). Since 2010, it has been extended to most urban renewal districts city-wide. Typically, TIF funding is pooled with other sources of funds, such as low income housing tax credits (LIHTC) and state funds. (Additional history of the program is described below). In general, city policy now provides that 40 percent of revenues from tax increment funds in urban renewal zones are to be set-aside for affordable housing. (The policy is waived for some purely industrial urban renewal areas).

Since its inception the program has helped subsidize the construction of several thousand affordable housing units in urban renewal areas citywide. In the city’s largest urban renewal area, the River District (which includes the rapidly growing Pearl District), the program has generated $83 million in TIF funds which have helped support the construction of about 2,200 affordable housing units. Pearl District affordable housing projects are interspersed with market rate housing in the area. (Red buildings were affordable housing.)

The number of housing units financed through the TIF program is significant, especially when compared to the output of other programs local governments have enacted to try to create more affordable housing, such as inclusionary zoning requirements. The total number of units of housing constructed with assistance from the TIF set-aside in Portland’s river district exceeds the number of inclusionary housing units built in all but a handful of cities.

Policy advantages of TIF

Using TIF funds for affordable housing has two especially of desirable properties:

1. TIF funding doesn’t add costs for developers or impose additional development restrictions. Once a TIF district is established, the provisions are essentially invisible to developers. Moreover, developers pay the same property taxes whether they build inside the TIF district or not. The TIF diverts the taxes that would have otherwise been collected by the city (and other tax levying entities) for the life of the TIF district. Thus, unlike other measures (impact fees, inclusionary zoning requirements), TIF financing doesn’t dis-incentivize housing construction or development.

2. TIF captures tax revenues both from the value of new investment in the area and the appreciation of existing properties (developed and undeveloped) in the district. Revitalization tends to increase the property values of existing residential, commercial and industrial land and improvements, and result in higher property tax revenues for the city. TIF then allocates a portion of these property tax revenue increases to affordable housing.

Portland’s program was subject to media criticism for falling short of an announced goal that a certain percentage of all the housing in the River District would be affordable–it produced about 2,200 units, short of a goal of about 2,400 units. Public officials should be cautious in setting expectations for TIF financed housing.

One important limitation of the TIF program in Oregon (which is typical of most states), is that the revenues raised in the district must be expended in the district. Portland is precluded, for example, from building housing in one district with funds from another district. In the case of the River District, this requires the city to build housing in a high cost area. This has positive and negative effects: It assures that new affordable housing gets build in high cost and high income areas, promoting socioeconomic integration; on the other hand, it likely increases the cost per unit of affordable housing, and reduces the total number of affordable units that could be built with public funds.

Tax increment financing has rarely been used as part of an inclusionary housing program. A recent survey by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy of 250 inclusionary housing programs nationwide reports that only 20 programs (8 percent of those surveyed) provided a direct public subsidy (including tax increment financing). Thaden, E., & Wang, R. (2017). Inclusionary Housing in the United States: Prevalence, Impact, and Practices Working Paper WP17ET1 (Working Paper No. WP17ET1) (p. 67). Washington, D.C.: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

History of Portland’s tax increment financing for affordable housing program

In 2006, the Portland City Council adopted the original Set Aside Policy, requiring that “30% of Tax Increment Financing (TIF) over the life of an Urban Renewal District shall be dedicated to the development, preservation and rehabilitation of housing affordable to households with incomes below 80% median family income.”

The Council modified that policy in 2011, to replace change the applicability of the set-aside from each individual urban renewal district to all urban renewal districts, collectively, city-wide.

In 2015, the City Council voted to further revise the program by adopting set-aside amounts for each of the city’s urban renewal areas, with amounts set aside for affordable housing being tied to the opportunity for housing development in the area. Several renewal areas are industrial districts with less land suitable for housing development.

Appendix

Tax Increment Funds Dedicated to Affordable Housing in Portland, 2006 to 2016

| Urban Renewal Area | 8 Year Set-Aside |

| Central Eastside URA | $5,236,964 |

| Downtown Waterfront URA | $17,457,873 |

| Gateway URA | $9,462,159 |

| Interstate URA | $29,780,785 |

| Lents URA | $23,742,202 |

| North Macadam URA | $28,238,027 |

| Oregon Convention Center URA | $10,903,583 |

| River District URA | $83,090,101 |

| South Park Blocks URA | $35,550,080 |

| Total, All URAs | $243,461,774 |

| Fiscal Year | Annual Set-Aside |

| FY06-07 Actuals | $19,698,857 |

| FY07-08 Actuals | $20,412,794 |

| FY08-09 Actuals | $26,908,476 |

| FY09-10 Actuals | $41,891,776 |

| FY 10-11 Actuals | $27,221,625 |

| FY11-12 Actuals | $43,096,200 |

| FY 12-13 Actuals | $28,004,694 |

| FY 13-14 Actuals | $7,384,641 |

| FY 14- 15 Actuals | $18,292,019 |

| FY 15- 16 Actuals | $10,550,691 |

| Total, All Fiscal Years | $243,461,774 |

Source: Portland Development Commission/Prosper Portland.

Are all the money diverted by the TIF a net loss in revenue to the City/County so there will be fewer services to the city as a whole by setting this money aside?