This post is written by Jimmie Covington, veteran Memphis reporter with lengthy experience covering governmental, school, and demographic issues. He is a contributing writer with The Best Times, a monthly news magazine for active people 50 and older, where his articles also appear.

By Jimmie Covington

Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland and his administration have a major goal of reversing the decades-long pattern of people moving out of Memphis.

However, U. S. Census Bureau estimates released in April don’t indicate any trend in that direction. The estimates are for the nation’s counties and metropolitan areas on July 1, 2018.

It’s now less than a year before the next 10-year federal census will be conducted. The official census day is April 1, 2020. The first results are due out in December 2020.

The census is mandated by Article 1, Section 2, of the U.S. Constitution. The major purpose is to determine how many representatives each state has in the U.S. House of Representatives

The 2020 Census will give us a much more solid picture than the estimates of what is happening with the population locally, in the state and in the nation as a whole. Once the results are in, the annual census estimates that have been released will be adjusted to conform with the changes that are reflected in the 2020 Census count.

For now, it will be several weeks before the July 1, 2018, estimates are released for Memphis and other cities across the nation.

But unless there has been a highly unlikely change from what Shelby County estimates in the past have revealed about Memphis, the figures indicate the city is continuing to lose thousands of people to outward movement each year.

The estimates show that Shelby County had 935,764 residents, a decline of 209 from the previous July 1 but an increase of 8,082 from the 927,682 census count in 2010.

However, the newly released numbers also show that the county had 46,461 more resident births than deaths since 2010, including 4,424 more births than deaths between July 1, 2017, and July 1, 2018. That’s called a “natural increase.”

Or to put it another way, Shelby County had a population loss of 209 between July 1, 2017, and July 1, 2018, despite having 4,424 more resident births than deaths. If the census estimates are anywhere near correct, that means a lot more people are moving out of the county than moving in.

But what part of the county are they moving from? Here is where Memphis comes in.

For decades, census counts have shown that the only times that population has declined in the county outside Memphis have been when the city completed major annexations.

The city is now effectively blocked from making any more annexations and is moving to de-annex some areas.

Over the decades, the pattern has been that all of Shelby County’s slow growth in population could be linked to people moving out of Memphis.

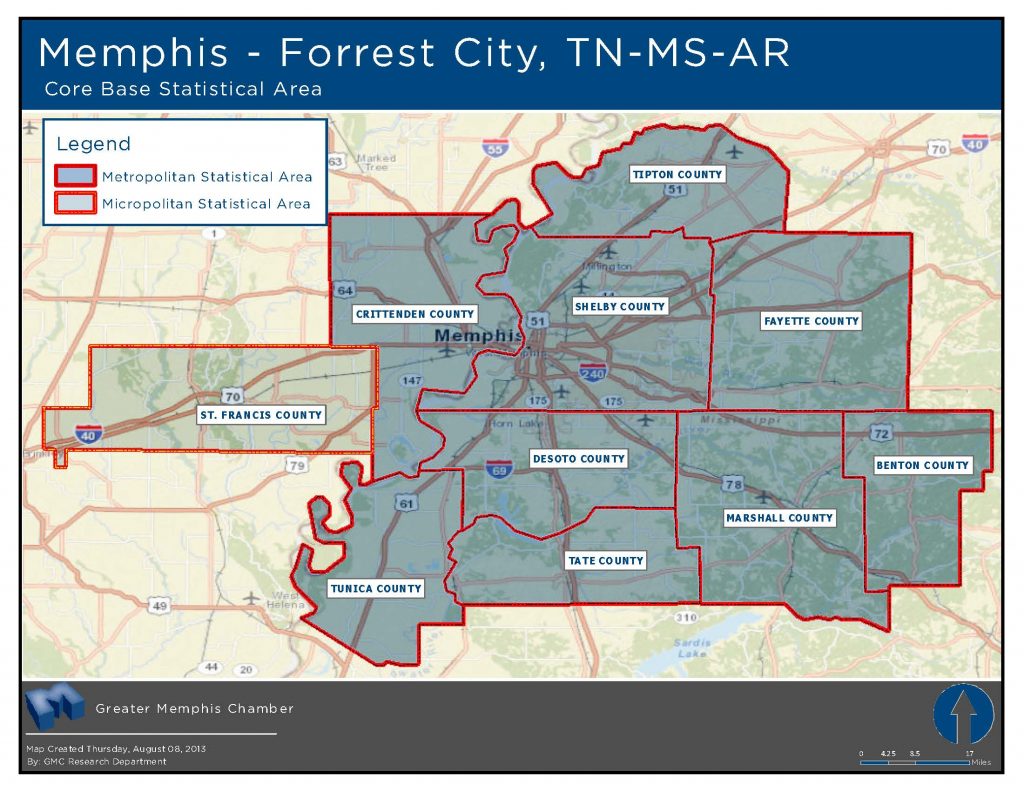

The latest estimates also continue to show that people are not just leaving Memphis, they are leaving the nine-county Memphis metro area as a whole.

The estimates reflect that only two counties in the area – DeSoto County, Miss., and Fayette County in Tennessee — are having growth larger that the natural increase of births exceeding deaths.

The 2018 estimates also show that the population boom remains strong in the Nashville metro area. The 2018 estimate for the 14-county area is 1,930,961, an increase of 260,085 from 1,670,876 in 2010

The Nashville area ranks 36th in size among the nation’s metro areas. Memphis is 43rd. The 2000 Census was the first to show the Nashville area with more residents than the Memphis area.

Estimates for 2015 were the first to show Nashville moving ahead of Memphis to become the state’s largest city.

Shelby remains the state’s largest county with 935,764 compared to Davidson’s 692,587. Davidson’s estimated growth since 2010 is 66,027.

Here are the July 1, 2018, census estimates compared with the 2010 Census counts for the nine counties in the Memphis Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Counties 2010 2018

Shelby 927,682 935,764

Fayette 38,439 40,507

Tipton 61,006 61,581

Crittenden 50,906 48,342

DeSoto 161,267 182,001

Benton 8,728 8,271

Marshall 37,145 35,451

Tate 28,878 28,759

Tunica 10,778 9,944

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

Very Interesting. Let me add some income data to go with that.

Per Capita Personal Income 2017

Change from 2016

Shelby $47,655 2.9%

Fayette $53,942 3.2%

Tipton $37,515 3.0%

Crittenden $36,589 6.1%

Desoto $39,461 2.8%

Benton $29,022 2.3%

Marshall $31,238 2.2%

Tate $34,873 2.6%

Tunica $31,814 -5.5%

The big surprises for me are Fayette (I still think of it as the basket case of the 1960’s when it has become an affluent suburb) and Tunica (I had no idea that gaming was a failure for both population and income)

Perhaps Memphis should add Craighead County to it geographical region.

My hope is Memphis and this region will solve the public transit issue and create a transit system that will accommodate future population growth. Unlike what has happened to Nashville and its surrounding area.

Many people do not seem to realize that the census estimates show a net outward movement of people from the nine-county area as a whole. It seems to me that Memphis and Shelby County elected officials almost totally ignored the results of the 2010 Census. I never saw a quote from any of them in any publication that indicated an understanding of what the numbers were. People can have different views of what census numbers reflect but to have any real understanding they have to know what the numbers are. I never saw any kind of analysis of the movement into and out of Shelby County of various age groups by race after the 2010 Census. Maybe someone did one and the weakening media never discovered it. I attempted one after the 1990 census. A government agency did such an analysis after the 1980 Census. As I recall the findings after the 1990 Census included a population loss among African-American women in their 20s and a gain among white women in their late teens and early 20s. Explanations that I received during interviews were that young black women who went off to college and perhaps many who completed their college work here were finding better job opportunities elsewhere while young white women from rural areas and small towns in the Mid-South were attracted here by jobs at hospitals, other medical facilities and businesses.

Of greater concern than net population loss/gain is the change in prosperity of the people who live here continuously. A booming population might make life great for developers and contractors and is good for the community ego, but it is not necessarily of any benefit to the native citizens. When you consider the income gap between our region and the average metro area, it is clear that our region has considerable room for economic growth just by bringing the existing populous up to the educational, skills and productivity levels of our peer cities.

Is that happening? We are told by the statistics that our population is stagnant but we see nice new apartment buildings going up all over downtown, midtown and the UofM area. If this construction is not driven by population growth, it must be replacement stock which is indicative of at least some degree of economic improvement within the urban core, at least.

Another potential indicator of economic growth without population growth is airport passenger traffic. Since MEM was dehubbed by Delta in 2014, it has seen consistent 5% year-over-year growth in emplaned passenger counts. Some of this is certainly due to reduced fares resulting from increased competition, but an 800K increase in annual passenger counts (3.6M to 4.4M) from 2014 to 2018 is some combination of a lot more visitors and a lot more people who can afford to fly.