Finally, something good came out of Graceland’s ham-handed and inept approach to negotiating with City Hall – Memphis’ first Community Benefits Agreement.

While it’s arguable that the $750,000 investment in Whitehaven by the tourist attraction is commensurate with the incentives that it’s already getting from city, county, and state governments, there should now be a policy for all developers and corporations receiving government incentives: every incentive should be accompanied by a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA).

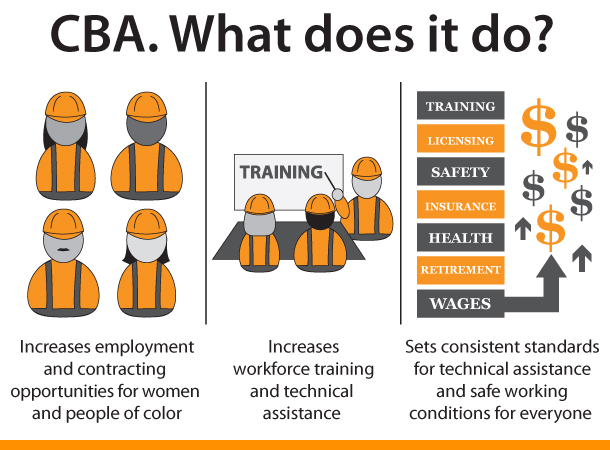

CBAs have been used in other cities for more than a decade for major development projects – from basketball arenas to residential and commercial projects. It’s a community development tool that requires a developer to take specific actions benefiting the local community in return for the incentives. Normally, the CBA is expressed as a contract between the developer or recipient of the incentives and a community coalition that will partner to achieve and ensure that the conditions of the agreement are delivered.

At this point, the agreement is contingent on City Hall supporting Elvis Presley Enterprises for more incentives that the company says it needs to make additional improvements.

Saying Grace

The Graceland CBA requires Elvis Presley Enterprises to invest a minimum of $750,000 in Whitehaven over five years and agree to pay new fulltime positions a minimum of $15.50 an hour. Although $15.50 these days passes for a living wage in Memphis (and it’s not unless you are unmarried with no children), it does amount to progress.

All in all, while the investment in Whitehaven averages only $150,000 a year, it will hopefully stimulate jobs that are not more of the low-skill jobs most often created by the tourism industry.

The CBA concept was first advanced several years ago in Memphis by City of Memphis Director of Housing and Community Development Paul Young as part of the proposal for redevelopment of the Fairgrounds into a youth sports complex. The Graceland CBA will be the first one actually consummated, and hopefully, there will be many more.

Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland said he hopes the Graceland agreement will become a precedent for other development projects. Every neighborhood in Memphis hopes so too.

Bullish Behavior

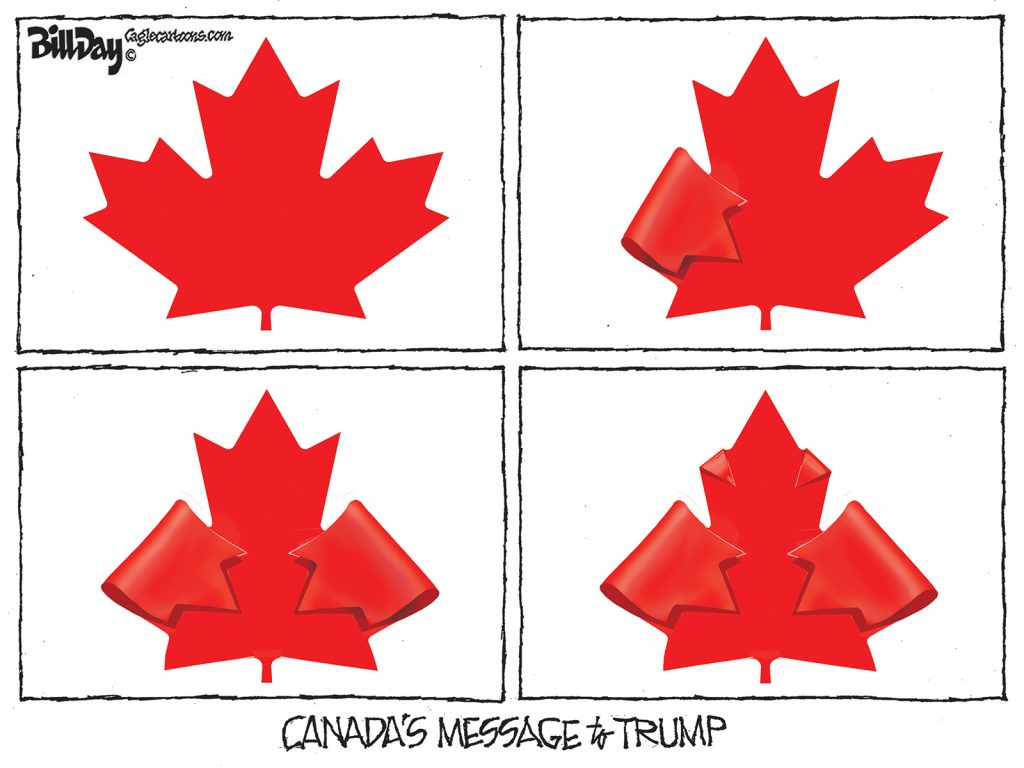

In its negotiations with City of Memphis officials for more incentives, Graceland has shown all the finesse of the proverbial bull in a china shop, particularly in the way it has cavalierly dismissed city concerns about whether the new arena at Graceland could violate the non-compete agreement between City of Memphis, Shelby County Government, and the Memphis Grizzlies.

Perhaps, only the county wheel tax is shrouded in as much misinformation as the non-compete agreement, but it’s arguably the best agreement negotiated by the public sector. IAgainst all predictions to the contrary, city and county governments were successful in making the Grizzlies pay operating deficits at FedExForum and require the team to remain in Memphis for 17 years.

With the Grizzlies paying operating costs for the Forum that are estimated at about $7 million a year (Nashville taxpayers are responsible for paying roughly that amount as the operating deficit for its NHL arena), with the Pyramid closing and taking with it a deficit of about $2 million a year, and with a closed Mid-South Coliseum eliminating about $2 million a year in operating costs, it means that taxpayers here have saved about $150 million since FedExForum opened.

Fiduciary Responsibilities

All that is to say that city officials’ concerns about violating the non-compete agreement and allowing the Grizzlies off the hook with operating costs, if not voiding the existing agreement and reopening negotiations between local government and the team, are well-placed and the right position to take in their fiduciary responsibilities to the public.

That said, the same fiduciary responsibility should lead local officials to follow the lead of other cities and create the requirement that no incentive will be approved here without a CBA to go with it.

The following is a blog post we published October 27, 2014, The Perfect Marriage: PILOTs and Community Benefits Agreements:

Note: Community Benefits Agreements are being used in cities across the United States to set out what companies and developers will do for the community in return for generous public incentives. Here, it could be a useful addition to our tax freeze program and restore public confidence in it.

It’s a buyer’s market for companies looking to locate in Memphis. About $80 million in tax waivers given out by Memphis and Shelby County remain in effect. More tax freezes have been approved here than in seven other major Tennessee counties combined, and it’s hard to find a city in the U.S. with a similar over-reliance on them.

Economic development officials have said for 25 years that these financial inducements are necessary to bring new jobs to Memphis because of problems with our workforce, but little has been done to improve the workforce over the same period of time. More to the point, local government has a history of approving property-tax freezes for companies with the low-skill, low-wage jobs that were more and more headed for third-world countries.

All that said, it’s still hard to argue with the decision to open the city, county, and state government cash registers for Electrolux and Mitsubishi.

It’s All About Context

There has been some political blowback as a result of the $179 million for 1,240 direct jobs at Electrolux paying an average of $31,000 and $34 million for 281 jobs at Mitsubishi paying an average salary of $50,000, because the average incentive per job is about $140,000 — a number normally associated more with incentives for auto manufacturing jobs. (In essence, government is building the plant for Electrolux.)

And yet, incentives for new jobs have to be considered within current economic realities, and times have been hard for Memphis. As the Greater Memphis Chamber of Commerce pursued these companies, it was not lost on them that our economy had lost almost 35,000 jobs in the past nine years and in a ranking of the 100 largest regions, our region was ranked 89th in private sector jobs growth.

Job loss often begets more job loss because a city is seen by companies as in decline and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. That’s why Chamber officials were desperate to change our narrative. But the really good news is that, supported by former Tennessee Governor Phil Bredesen, Memphis Mayor A C Wharton, and Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell, they were able to do more than just add 1,521 direct jobs and about twice that many indirect jobs.

Reasons

First, these jobs are in the urban core where existing infrastructure can be used without expensive new investments by taxpayers. Second, these are 1,521 manufacturing jobs, which continue to be the gold standard for cities like ours without a deep knowledge economy and with the need for jobs that pay more than just a living wage.

Third, these two plants — Electrolux will build ranges, wall ovens, and cooktops in 700,000 square feet, and Mitsubishi will build 400-ton, boxcar-sized electrical transformers in 330,000 square feet — could expand Memphis’ export economy beyond our traditional trading partners of Canada, Mexico, United Kingdom, Japan, and Germany into the emerging markets in South America, India, and China.

Memphis and Shelby County governments agreed to split $44 million in local incentives, and once again, our Noah’s Ark approach to funding projects means that Memphians pay a disproportionate share, paying 100 percent of the city’s $22 million and then paying about 70 percent of the county’s $22 million.

Tourniquet

Simply put, Memphis and Shelby County needed to do something dramatic to stop the bleeding of jobs and combat the negative trend lines for our economy. There’s no question that these kinds of large subsidies and incentives are unsustainable as long-range economic development policy, but on these two projects, the Greater Memphis Chamber of Commerce had little option but to adopt the approach that if you find yourself in a hole, the best thing to do is stop digging.

That said, if Memphis and Shelby County are to continue their over-reliance on tax freezes, it’s time to consider Community Benefits Agreements for companies that receive public incentives. These agreements — contracts between a company and a community coalition — set out the benefits that the city will get in return for its incentives. The most common benefits are living wages, local hiring, job training, environmental remediation, and funding for community programs.

For example, in an agreement in Washington, D.C., a company agreed to hold a job fair, to sponsor field trips for students, create hiring preferences for neighborhood residents, support for an arts festival, and internships. In cities like Atlanta, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Milwaukee, and Seattle, these agreements have come from a grassroots movement demanding a reciprocal arrangement with new businesses. Memphis could be a pioneer by making these community benefits agreements part of the public approval process for tax freezes and subsidies.

Previously published in the May, 2011, issue of Memphis magazine.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.