For almost half of Memphis’ 200 years, the city has been looking for ways to create a great riverfront. As legendary city planner Harland Bartholomew suggested in the city’s first comprehensive plan in 1924, there is so much potential for the riverfront to be put to a more profitable use for the city. Over the years, the emphasis there, as in so many parts of Memphis, was more about projects than placemaking, and as a result, the ultimate potential of the riverfront remained to be achieved.

If various plans have proven anything, it is that there has been no lack of good ideas. Rather, the obstacle has been the civic will needed to implement them in a coordinated way in pursuit of a cohesive vision. The good news today is that there is now that kind of vision for six miles of the riverfront, and pieces have already been put in place by the Memphis River Parks Partnership. With the start of the cobblestone restoration later this year and the promise of a spectacular Tom Lee Park, the possibilities that have been obscured for so long are coming into view.

In a year when Memphis celebrates its official 200th anniversary, it’s a good time to look back at all the previous riverfront plans in hopes that this time we get it done.

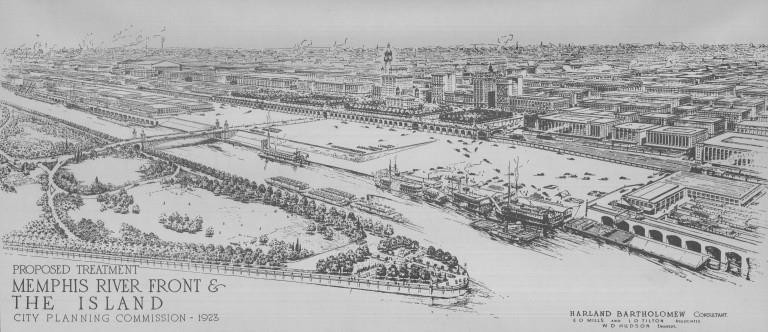

THE CITY PLAN OF MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE (1924)

In Memphis’ first comprehensive plan, city planner Harland Bartholomew included a grand gateway and arrival point with a “riverfront plaza” in classical architectural forms. While the Planning Commission supported the idea and even used the rendering of the proposed riverfront as its frontispiece, it had no political traction and no action was taken to capture the vision of a new riverfront.

In describing the riverfront as one of the “city’s most highly prized assets,” Bartholomew wrote: “Of greater foresight, however, was the reservation (by the surveyor who laid out the original city) of a ‘promenade’ and public landing place along the river. It was a far-seeing vision which recommended that the riverfront be made an attractive place and reserved for public use. Unfortunately, however, these excellently conceived features of the first town plan of necessity had to be abandoned. The shifting of the river eventually made the original public landing inaccessible to boats and what is now the public landing took the place of the promenade.

He wrote: “…The dominant function of this portion of the city seems likely to be always utilitarian. Memphis will probably never sacrifice transportation advantages to recover the old promenade. Any plan for improvement of the district, therefore, must be predicated upon this fundamental assumption. It is possible, however, to make a busy, purely utilitarian waterfront attractive. Such sections are never uninteresting, especially if they be well-arranged and kept neat and clean. The riverfront is the front yard of Memphis. While at first it may seem difficult, if not prohibitive, to make a satisfactory plan of riverfront development, such is not the case, for quite the contrary is possible. Today, the riverfront is not merely unattractive, but represents a flagrantly unprofitable use of the property….With proper architectural design, attractive lighting, and the exercise of care in both public and private construction, this riverfront could be transformed into a picture of combined commercial and recreational activities truly representative of the city’s character and unsurpassed in attractiveness in any other city.”

CIVIC CENTER PLAN (1959)

The City Commission accepted a plan prepared by the Memphis League of Architects that called for creation of the Civic Center to stabilize the northern end of downtown, creation of a pedestrian mall to take the place of Main Street (which happened 15 years later in 1974), and for the city to exploit the panoramic view of the Mississippi River with the DeSoto Memorial Tower, a 350-foot pylon-like toward with an observation deck at the top, to be built as an iconic presence on the riverbluff. At the turn of the century, a pyramid had been suggested and rejected, and the observation tower met a similar fate.

BLUEPRINT FOR MEMPHIS (1973)

Future Memphis, a CEOs organization of 100 leaders, called for a revitalized central business district, more hotels to serve the convention center, and the development of the riverfront for residential and recreational purposes.

DOWNTOWN PLAN (1974)

Marcou, O’Leary and Associates’ downtown plan included recommendations for a “Promenade Gateway,” a galleria concept including shops, commercial office space, and a hotel in the area of Court Avenue extending from the Mid-America Mall (Main Street) to near the Mississippi River riverfront. It also recommended Volunteer Park (Mud Island).

MEMPHIS RIVERFRONT STUDY (1978)

In its Riverfront Study, Memphis and Shelby County Office of Planning and Development recommended a “riverfront garden walkway” with a “performing arts barge, an open air marketplace, barges or piers, marine service, and better mooring for riverboats.”

CENTER CITY RIVERFRONT PUBLIC SPACES PLAN (1982)

Mitch and March Hall, commissioned by Center City Commission (now Downtown Memphis Commission), gave detailed recommendations for a path system and ways to beautify public spaces that gave momentum to the bluff walk for the riverfront. Among their suggestions were to improve the public promenade with new landscaping, a bridge to cross over Court Avenue and better access to west side of Cossitt Library; to renovate the cobblestones and add a floating dock system; and construction of a bluff walk that includes a footpath over Riverside Drive to Tom Lee Park.

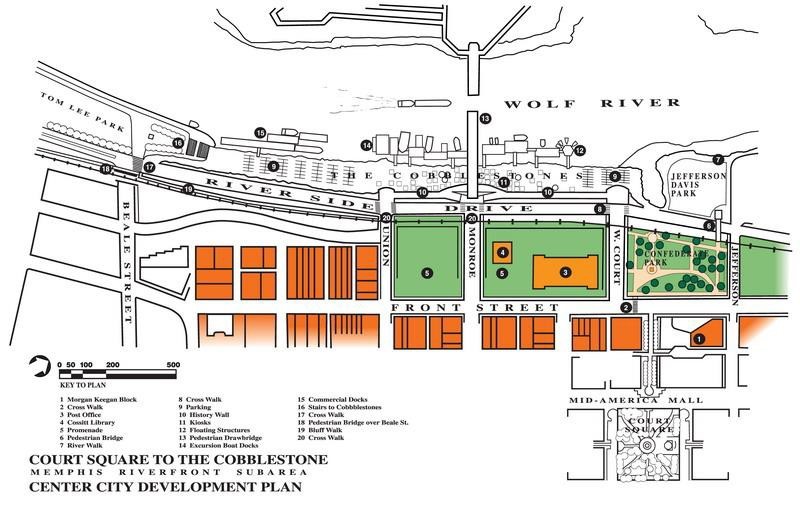

CENTER CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR THE RIVERFRONT SUB-AREA (1987)

This plan, by the firm of Venturi, Rauch & Scott Brown, included a pedestrian bridge to Mud Island, a Mud Island Aquarium, and a collection of kiosks on the Cobblestones. “The Memphis riverfront is completely unique with its unspoiled natural amenities, its lack of industrialization, and its general accessibility and proximity to Downtown. Historically, the river and the bluffs determined the very establishment of the city at this point. Favored by the natural beauty of the river and a dramatic view to the fertile Arkansas flood plain, the Memphis riverfront offers young and old a serendipity for the senses and an easy escape to nature…At the bluff edge, handsome stone parapets should be constructed. Walkways should make frequent connections to Front Street to encourage pedestrians to meander away from the street to experience the river views and breezes.”

The plan’s recommendations included: (1) improving the Promenade as a grand civic open space connecting the river with downtown; (2) historic restoration of the cobblestones and making the wharf area into a place to visit with such amenities as floating restaurants and places for art; (3) something special at the foot of Beale Street; (4) a bluff walk with pedestrian bridges to cross over Riverside Drive from the bluff to Tom Lee Park; (5) a pedestrian drawbridge at Monroe Avenue to connect with Mud Island; and (6) the addition of an aquarium to Mud Island River Park.

RIVERFRONT BICYCLE AND PEDESTRIAN SYSTEM AND RIVERSIDE DRIVE BEAUTIFICATION MASTER PLAN (1992)

This report established the plan for the Bluff Walk. Much of this plan has been built and it is impossible to imagine the riverfront today without this special way to enjoy the riverfront and revel in its various river views.

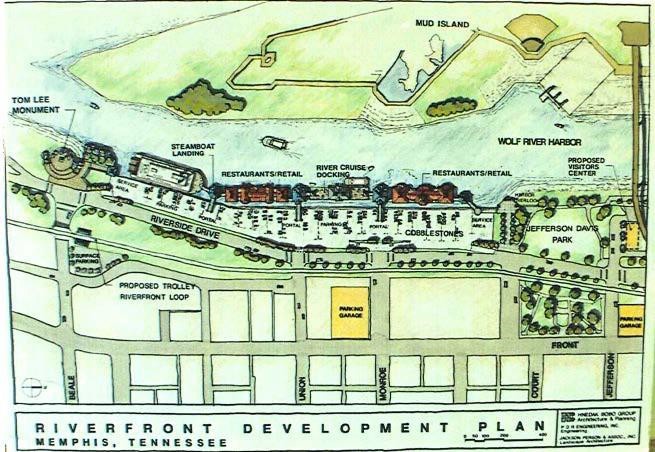

MEMPHIS RIVERFRONT PROPOSAL (1996)

Completed by the Riverfront Redevelopment Task Force of the Downtown Redevelopment Planning Committee, its recommendations included turning the Wolf River Harbor into a recreational basin with boat rentals for crew, canoeing, sculling, and kayaking. It also proposed a casino on Mud Island. In addition, it recommended a waterside restaurant row below the cobblestones. Since then, better understanding of how waterfront entertainment districts operate suggests that an isolated collection of shops and restaurants is less likely to thrive than one better integrated into either existing urban fabric or a broader collection of civic and residential uses. This report also recommended the creation of Riverfront Development Corporation.

WATERFRONT PLAN (1999)

The Waterfront Center was hired to work with the public to develop ideas for the riverfront. Those ideas included free, year-round access to Mud Island River Park, slower traffic on Riverside Drive, protection of the cobblestones, better docking for river tour boats, and eliminating Mayor Herenton’s idea to turn the harbor into a 28-acre lake.

MEMPHIS RIVERFRONT (2002)

Completed by the highly respected planners at Cooper Robertson for the Riverfront Development Corporation, the Memphis Riverfront plan has been called by author and New Urbanist Jeff Speck as “perhaps the most skillful and ambitious American design effort of the past decade.” By creating a neighborhood-size land bridge south of I-40 connecting Mud Island to the mainland, and making a lake out of the Wolf River Harbor, this plan envisioned the city truly embracing its waterfront, fundamentally changing its relationship to the Mississippi and its likely visual appeal. The report notes that Paris, Portland, and Pittsburgh all deal with fluctuating river levels, and expressed concern about the promenade as a barrier between downtown and riverfront. Discussing traffic patterns, the Riverfront plan noted that Riverside Drive is another barrier between the downtown and the river, and that a proper redistribution of traffic throughout the downtown grid would take pressure off this street and allow it to flourish.

URBAN LAND INSTITUTE REPORT ON MEMPHIS RIVERFRONT (2003)

This report by the leading real estate think tank was completed just after the Cooper Robertson plan, which it generally supported. Its relevant recommendations included:

* Support for the land bridge, albeit on a deferred timeline, and perhaps smaller.

* Connecting Beale Street Landing better with Beale Street.

* Clearing the bluff of (visible) parking structures and recreating it as the Grand Esplanade.

* Developing the west side of Front St. with mixed-use buildings rather thanopen space.\

* Adding a water taxi connection to Mud Island.

BEALE STREET LANDING (2003)

Plans for a dramatic docking facility and restaurant promise a powerful connection to the Mississippi at the foot of Beale Street. It is strategically located where the historic Cobblestone Landing meets Tom Lee Park, directly across the Wolf River Harbor from the tip of Mud Island. Its design was selected through an international competition entered by 170 architects from 20 countries and 28 U.S. states.

FRIENDS FOR OUR RIVERFRONT (2004)

The recommendations opposed Cooper Robertson plans and supported a vision for the entirety of the bluff to become a continuous public park, albeit one that preserves the historic structures of the University of Memphis Law School and Cossitt Library.

A FRESH LOOK AT THE MEMPHIS RIVERFRONT (2007)

Sponsored by the Friends for Our Riverfront, this report was completed by the Project for Public Spaces and included recommendations for reducing both Riverside Drive and Front Street to two lanes of traffic, connecting the individual bluffs with bridges, demolishing the bluff parking garages, and demolishing or reusing City of Memphis Fire Station and Headquarters.

THE COBBLESTONE LANDING (2008)

The challenge of the Cobblestones is twofold with twin objectives of preserving the past and enlivening the present. The central and largest feature of the cobblestone landing is that it is a rocky slope too steep to meet current safety and handicap codes and too historic to allow for the sort of reconstruction that would render it more usable. The plan calls for preserving the historic nature of the cobblestone landing, and a question to be answered is if it can then be used for other uses that bring people to the river’s edge, such as temporary installations.

MUD ISLAND RIVER PARK LAND USE STUDY (2010)

Completed by Looney Ricks Kiss (LRK) for the Riverfront Development Corporation, this land use study was executed with substantial public involvement, and included an urban design effort that went well beyond mere land use. It considered a full range of outcomes, from minimal change to a complete replacement of the River Park with mixed-use development. The ultimate outcome was a proposal that restores and improves the current Park, Museum, and Amphitheater while introducing a sector of mixed-use development between the park and I-40. Other relevant features include vertical stair/elevator towers in Jefferson Davis Park and east of the current; a museum, dramatically shortening the distance of the walk from downtown to Mud Island; a water taxi connecting many locations along the Wolf River; a pedestrian bridge connecting Beale Street Landing to the tip of Mud Island; the potential of a vehicular bridge connecting to Mud Island along Poplar Avenue; the reshaping of the marina to allow expansion of the developable property to its west; the southward extension of Island Drive and its adjacent Greenbelt Park well into the new mixed-use area south of I-40, and improvement to the existing park made possible in part by revenues associated with the development of this mixed-use property.

“EXPERIENCE THE RIVER,” AN INVENTORY OF CURRENT RIVERFRONT PROPOSALS (2011)

This overview document by O.T. Marshall Architects for the City of Memphis was not a plan but collected different design proposals and modifications for the Pinch District and riverfront. It called for improvements to Tom Lee Park, connectivity between parks and attractions, and placing a three-block-long row of shopfronts on the west side of Front Street. It also analyzed the opportunities for a reinvigorated Pinch District that included renderings.

In conjunction with this inventory, City of Memphis commissioned RKG Associates Inc. for a report, ASSESSMENT OF DOWNTOWN AND RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS (2011), whose purpose was “to examine the array of planned and ongoing development projects along the city’s waterfront in order to help establish priorities for public sector action and funding.” Recommendations related to the riverside included focusing on the Beale Street corridor between Beale St. Landing and the night life to its east, paying special attention to the City-owned parking lot between Front and Main Streets; resolving issues surrounding the Promenade now; examining the possibility of making Riverside Drive more pedestrian friendly, including street tree planting, parking, and lane reductions; planning for a higher use of Mud Island, and finding a way to allow for more active use of the Cobblestones.

MEMPHIS RIVERFRONT ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS (2013)

Author, New Urbanist, and architect Jeff Speck, in consultation with Nelson/Nygaard Transportation Planners and urban planner Toni L. Griffin – was hired by City of Memphis to review 25 years of studies about the riverfront to develop short term, actionable recommendations to bring more activity, more people, and more vitality to downtown. The six priorities: (1) Make Riverside Drive a complete street; (2) Make Bass Pro Drive a complete street; (3) Encourage development along Bass Pro Drive; (4) remake then-Jefferson Davis Park; (5) complete the central Bluff Walk; and (6) improve Tom Lee Park with “rooms.”

MEMPHIS CIVIC COMMONS (2016)

The Strickland Administration’s Civic Commons plan, which received a $5 million grant from JPB Foundation, Knight Foundation, Kresge Foundation, and Rockefeller Foundation, focused on The Fourth Bluff project, four blocks of downtown Memphis deeded by the city’s founders for public use, linking prominent public assets concentrated together along the Mississippi River to bridge urban connectivity gaps that are both cultural and physical. The assets include Cossitt Library, University of Memphis Law School promenade, and the Memphis and Mississippi River Parks. The project bridges fragmented pedestrian connections that separate cultural assets and the riverfront and addresses negative public perceptions through reinvestment and community partnerships.

A popular initiative of the Civic Commons plan was the launch of RiverPlay which converted a section of Riverside Drive into an activated urban space to acquaint more people with the two infrequently-visited parks on each side of it. It embraced a sense of fun with a pop-up park that featured shaded places to sit and talk, places to run, a roller skating rink, three half-court basketball courts, and local food trucks. RiverPlay built on the momentum of the Fourth Bluff’s highly successful ice rink the previous winter, which drew 8,000 people in just a few short months. The ice rink’s popularity demonstrated that additional programming and activity will draw even more people to the Fourth Bluff over the summer. The initiative also set the stage for the development of Mississippi River Park into the whimsical and popular River Garden.

REPORT BY GEHL STUDIO (2016)

Design firm Gehl Studio, with offices in Copenhagen, San Francisco, and New York City, provided its observations about the Memphis riverfront in a public presentation culminating a two-day on- the-ground study. Matt Lister and Blaine Merker of the firm labeled the riverfront a “huge asset,” particularly the “miles of public waterfront access,” and praised the sunset over the river’s floodplain and the opportunity to connect the riverfront to a citywide trail network. They pointed out that the lack of connectivity makes it difficult to travel from one segment to another and treats them as isolated pieces. In addition, they emphasized the civic mental divide between downtown and the riverfront and that the streets between both should be activated. The key to success is for a public commitment that says “we want a world-class park on our world-class riverfront.”

MEMPHIS RIVERFRONT CONCEPT (2017)

Commissioned by Mayor Jim Strickland’s Memphis Riverfront Task Force, with support from the Hyde Family Foundation and the Kresge Foundation, Studio Gang released its Concept to redesign and redevelop a six-mile section of the Memphis riverfront into a network of spaces and opportunities tied into the city and its assets and that benefits the entire community and lifts Memphis as a whole. Focused on connecting the city and its citizens with each other and the river, it’s a look at public design that attempts to create a signature civic gathering space. The Concept focuses on creating a series of separate spaces, or zones, to create a changing, progressive experience. Within the five different zones – the Fourth Bluff, Mud Island, Tom Lee Park, Martin Luther King Riverside Park, and Greenbelt Park – terrain and layout differs dramatically as well as amenities, such as an adventure playground or an outlook where people can enjoy live music at sunset, that offers activities and experiences that appeal to people of all generations, backgrounds, and races. The Concepts are segmented into short, medium, and long- range plans that include shovel-ready projects that can quickly build momentum toward more development.

Three design principles – foster, restore, and connect – underlie the Concept’s recommendations:

* Foster positive encounters, civic pride and identity, and new understanding of the Mississippi River.

* Restore natural conditions, native ecology, and a more dynamic relationship between people and the river.

* Connect assets along the river, the riverfront to the city (downtown and the neighborhoods beyond) and people with each other.

Operating on the principle that one size doesn’t fit all for civic design, the Memphis Waterfront Concept contains myriad options and amenities to engage and invite different populations to enjoy the water and to individualize their own special experiences. Proposed paths and trails, made for different speeds of movement and interspersed with areas for rest and shad, ensure those of different ability levels can all have an enjoyable exploring the park, from cycling through the park to savoring a sunset.

The Concept suggests that redevelopment doesn’t just mean going forward. It also means looking back to the natural ecosystems that initially made the Mississippi Riverfront so vital and restoring these organic elements as a priority. Part of the Concept includes an Eco Hub on Mud Island; a peninsula in the river to study freshwater ecology in an active place for learning, teaching, researching, gathering, and simply enjoying the outdoors; and elevating visitors above the river in Greenbelt Park, where a thick arch of native trees directs views across the Mississippi and provides great habitat for birds and other animals. Below the walkway, visitors can explore a native wetland on foot or by kayak, depending on the rise and fall of the river. A variety of new amenities at Tom Lee Park, from an adventure playground to an elegant pavilion, would provide park users with many activity options in all seasons. Different types of trails would allow for different speeds of movement through the park, while areas of respite and shade encourage everyone to relax and take in the Mississippi.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

In the mid 1990s I worked with the city (HCD) on a simple plan to put restaurants on moored barges at the cobblestones. While far less comprehensive than other plans (but similar to elements in the 1978 Memphis Riverfront Study) it could have at least drawn people and consistent activity to the riverfront, and perhaps spurred further development. There really hasn’t been a restaurant overlooking the river since The Pier closed many years ago.

All these plans and very little action. This track record does not offer much hope going forward. Surely it can be done as it has in other places. Baltimore’s Inner Harbor is a good example, it went from an under-ultilized industrial dump to a vibrant attraction. I tend to agree that there needs to be more than parks along the water. I’d like to see some restaurants overlooking the river.

I would love to see a land bridge, lined with the proposed aquarium, restaurants and shops that cross the harbor, connecting the bluff to Mud Island like the Cooper Robertson design. I love the MRPP and Studio Gang design for the parks, but I believe there should be more done to invigorate Mud Island and having a walkable plaza of shops and restaurants would certainly bring Mud Island to life. They should also enclose the amphitheater, with a retractable glass roof,so that concerts could be held there year-round.

Pedro, I agree with you. They should also add a multipurpose space that could be converted into an ice skating rink.

The current Riverfront Plan, which is being rushed, is not as good as several of the previous plans. Why not slow things down and get it right. We need to look back at all of the plans and pick and choose the best ideas from them. Tom Lee should not be the priority but because of the donors involved it has become the priority. Mud Island should be where we start along with a stronger connection from the south end of the island to the Cobblestone/Beale Street Landing Area.

The plan has been in the works for more than two years with extensive public input. Exactly how do you define something being rushed. Maybe another 95 years?

Tom Lee Park is the priority because City of Memphis does not know what it wants to do with Mud Island. It’s not about donors. It’s about opportunity.