Published in the current issue of Inside Memphis Business.

Innovation in Memphis is often viewed the same way we see our music: in the rearview mirror.

Just as we know the names of the Sun Records’ Million Dollar Quartet and the legends of Memphis’ unique brand of soul music, we know the stories about Fred Smith, Pitt Hyde, Abe Plough, Kemmons Wilson, Clarence Saunders, Wallace E. Johnson, and Robert Church.

And yet, like our music, innovation is very much a thing of the present, a fact proven again with this year’s Inside Memphis Business Innovation Awards.

These role models of innovation could not come at a better time. After all, we live today in an innovation economy in which economists calculate that about 50 percent of U.S. GDP growth is attributed to innovation.

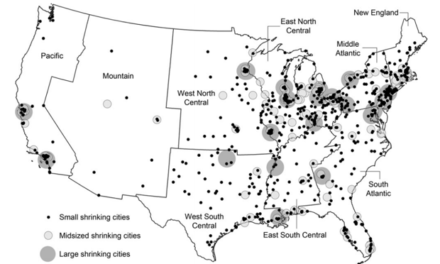

In its last City Vitals report, CEOs for Cities defined innovation by measuring patents, entrepreneurship, venture capital, and small business. In a ranking of the 130 largest MSAs, the Memphis region ranked #118 in small business, #117 in entrepreneurship, #60 in venture capital, and #67 in patents. In the ranking of just the largest 51 regions, Memphis trends toward the bottom, which speaks to the importance of celebrating current innovations and innovators whose success can inspire others.

The good news is there is renewed emphasis here on creating an ecosystem that breeds innovation and startups, particularly those technology-based ones that have an outsized impact on economic growth; however, it calls on us to be honest about the price we pay for our reliance on low-wage jobs.

Looking across all occupations, Memphis has a mean salary of $42,940, which is 78 percent of the mean salary in Minneapolis, 80 percent of Chicago, 85 percent of Atlanta, and 94 percent of Nashville.

“Usually, this would be represented as good news: you can move your business to Memphis, pay lower wages, and be more profitable, but the opposite may be true,” said David Ciscel, economist emeritus for University of Memphis’ Fogelman School of Business. “The lower salaries here – with a tradition of very low salaries for African American workers – will have the impact of thwarting economic development. The low salaries result in business sluggishness, the lack of need to innovate and invest to make a profit.

“Could it be our fate that Memphis salaries are just too low to inspire innovation and development in the local economy? Low wages do not inspire new capital investment. Business finds that using old technology is sufficient to make a good return – in the present. But without development, the future is very uncertain. The spurt that logistics clearly gave the local economy did not last, and part of the factor of regional stagnation may have been that Memphis wages, not just in logistics but throughout the local economy, were just too low to inspire large investment in innovative and labor-saving improvements to the regional economy.”

With our region’s historic reliance on agriculture and commodities and small margins for error, the focus was long on cheapness – cheap labor, cheap land, cheap utilities. In that environment, banks were timid with capital, especially venture capital, and the emphasis on cheapness in turn attracted more companies drawn by low costs and low wages.

The irony of our long-time mantra about a cheap place to do business is that some of the most expensive places in the U.S. with the highest wages and highest taxes are succeeding the most. That’s because they are investing in a culture of entrepreneurs and innovations. The kinds of companies that we are attracting to Memphis – and why people like FedEx executive and Greater Memphis Chamber chairman Richard Smith say we have to “up” our game – are those which avoid these economically dynamic cities.

Portland economist Joe Cortright, who has spoken in Memphis several times and understands its economy, said the environments of those cities drive innovation, because it is key to survival and success.

The opposite is also true: low cost locations like ours may actually insulate businesses from the need to be innovative. When costs are low and labor is low paid, mitigating risks, reducing human capital costs, and putting training on the back burner are priorities. Meanwhile, research suggests that cheap housing tends to attract and retain low-skilled workers, and as a result, low cost housing markets have lower skilled labor forces.

It is a vicious cycle. We have built a model of competitiveness that suggests low cost is always a winner, but in a rapidly changing innovation economy, it is the ability to create new breakthroughs, new products, and new businesses that are more and more the winning strategy.

In maintaining the labor force of the past, we ultimately weaken our ability to compete in the future. That’s why innovators matter so much. They are pointing us toward a better economy for Memphis.

This is all starting to sound like a broken record. Yes, the world knows that economy in the Memphis area is terribly weak, but all we seem to hear is more talk and constant moaning. Everything in this city seems to always be seen in the rear view mirror.

Innovation, small business, technology, venture capital, entrepreneurship, etc. always correctly rank Memphis near the bottom of everything. It is a vicious cycle that we will likely always be stuck in. Our continued simultaneous moaning and attempts at cheerleading are doing nothing to tangibly help improve the problems of this city and region. Talk is cheap and all we ever hear. There is simply no magic pill to cure this city’s woes, or to even point us toward a better economy.

I wish columnists could break the habit of making various income comparisons between Memphis and other cities around the country with vastly different costs of living. Those comparisons aren’t very meaningful, and instantly makes me suspicious of the writer’s motivation, qualifications, or both.

Scott: We hear you, and we’ve blogged several times over the years about the cost of living.

That said, we’re not aware of any research that indicates that college-educated workers who drive the economy base their decisions on where to live and work on cost of living numbers. We talked recently to a recruiter who was trying to convince a nationally prominent nonprofit leader to move to Memphis. There was a problem in reaching agreement on the salary, and we brought up the cost of living differential. His response was that workers who are coveted by cities today aren’t moved by cost of living comparisons. They are moved by the salary and how it compares with other cities. We were hoping for a different answer, but workers, particularly millennials, don’t seem to buy into our explanations about the cost of living.

And as we write, the low incomes here are actually an inhibitor for the level of innovation that we need to compete in today’s economy.

Good workers, especially millennials, want a city with a great quality of life in addition to a challenging job and advancement opportunities. Memphis falls far short in the quality of life category and most jobs here are just not that fabulous . They demand the requisite amenities, a cool vibe, and lots of things to do. They also want a city that’s well connected to other places and our dismal passenger airport is another big drawback. The lower cost of living is not a top priority for them. That’s why cities like Austin, Atlanta and Nashville are so attractive and growing so much.

From the Boyette Study, Louisville had the highest tax burden for HQ projects but they also have 35.5% total wage growth since 2010 compared to Memphis at 21.2%. From press reports, Louisville also has a relatively small economic development recruitment team compared to other cities. Given Louisville Memphis similarities in a border town and distribution hub, of all cities, I would be studying Louisville to gather ideas for best practices. One thing I am sure of is that they have a plan that is being implemented…..