We’ve written over the 13 years of this blog about the risks associated with hypnotizing ourselves with our own hyperbole, and as examples, we cited the overuse of “renaissance” to describe downtown as it languished a decade ago, the notion that The Pyramid was a “state-of-the-art” arena, and that our community’s stubborn poverty rate really doesn’t affect the rest of us.

Today, we don’t have to rely on exaggeration as much because there is a new optimism producing evidence of momentum and because of it, we have real bragging points and lessons we’ve learned, specifically on the importance of place in defining a city’s real economic success.

Maybe it’s just us, but in the face of this perceived progress, there seems less hyperbole in our discussions and our overstated talking points about Memphis. We’d like to think that today’s conversation is more grounded in results and a bolder agenda for what the future can and should be.

All of this is not to say that the obstinate grip of 180,000 of Memphis’ citizens by poverty is any less of a crisis, but now, as a result of grassroots persistence, the conversation about equity is at least on the table and hopefully, with a current of optimism flowing in Memphis, we will turn all the talk about buildings into importance, honest talk about people.

Falling One Place

In that vein, the celebratory attitude by some as a result of the Memphis region no longer being #1 in its poverty rate should not be allowed to become hyperbole that diminishes the priority for the Memphis region to tackle equity and opportunity in ambitious and sustained ways to reduce the number of families living in poverty.

That said, while celebrating that the Memphis region was no longer #1, it was almost lost that it was #2, hardly a reason for fireworks and parties. We quickly point out that despite the headlines in the media that routinely refer to Memphis being #1, and now #2, in poverty, they’re actually referring to the Memphis region.

Memphis itself is down the list around #6 or #7, but it is the anomaly of poverty rates outside Shelby County that drive our MSA to the top of the rankings. As we have repeatedly said here, although people living outside Memphis prefer to point at the city as the root of all problems in our region, the truth is that once you drive outside Shelby County, incomes drop and educational attainment falls.

It is an anomaly of the Memphis MSA, because in many regions we envy and which are prospering, once you drive out of Atlanta, Indianapolis, and Louisville proper and into the region, all of the key indicators go up, not down.

Moving In Right Direction

We hope that the 2.3% decrease in the poverty rate is the beginning of a downturn that continues, but the trend line for this community has been erratic over the years so we’ll have to wait and see. As for the child poverty rate, which finally dropped below 40% (it was 45.7% in 2013), we hope and pray that it is indeed the beginning of decline that takes us far from the top of this ranking.

Meanwhile, economists place more confidence in the Census Bureau’s Supplementary Poverty Measure which puts the national poverty rate at about one point higher than the regular Census Bureau report, and this becomes a cautionary tale for us as well.

The economist Timothy Smeeding who studies poverty and economic mobility found no reason to celebrate that the national poverty rate has declined – by a modest 0.4 percent – and said: “If this is the best we can do, it isn’t good.”

It was encouraging that Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland was in no mood to spike the football, and instead struck a similar position. “Our current rate remains shameful and reversing it is the challenge of our time but we must also acknowledge positive momentum when we see it,” he said.

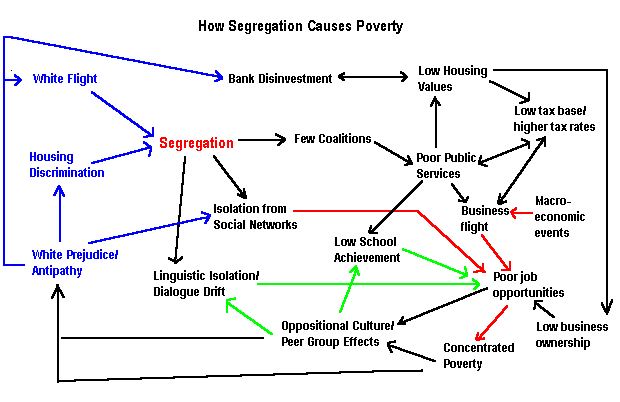

Reversing poverty in Memphis hinges on addressing the over-arching problem of economic segregation.

Connections

Memphis, both the city and the region, have too long fought problems, conditions, and lost opportunities that stem from the way that economic opportunity is always out of reach for too many people locked into neighborhoods of concentrated poverty. If the structural problem wasn’t difficult enough, the sprawl of the past 40 years has exacerbated the problem as it festered into economic measurements that have been doggedly difficult for Memphis to turn around.

Put simply, every problem becomes harder to address because of economic segregation, and it has gotten worse. Between 1970 and 2010, the number of high poverty census tracts in Memphis increased from 42 to 78, and they are now home to 104,150 people. These are the areas racked by an epidemic of foreclosures, outmigration has cut their population in half or more, proliferation of vacant houses increases blight and crime, and chronic joblessness is a fact of life for many.

Research by Harrison Campbell, associate professor of geography at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte, proves what Memphis has experienced. He concluded that when segregation is high in metro areas, their economies perform worse when compared to places with less segregation. More to the point, segregated regions have seen lower rates of income growth and lower appreciation of property values.

Here’s the kicker: the impact isn’t just felt by African American and Latino families in segregated areas of concentrated poverty. It’s also true for everyone, regardless of where they live: neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, the urban core, the city as a whole, the suburbs, and the entire region.

As for economic segregation, Memphis ranks near the top of that list with more than 80% of whites living in a community of other whites and about 75% of African Americans live in a community populated by African Americans.

The Right Attack

A common question asked of Professor Campbell is how exactly does the segregation of poor African American families drag down the economic opportunities for college graduates working in job centers. His conclusions is that as the spatial mismatch of jobs continues to get worse, and as employment opportunities sprawl, people in segregated cities are isolated more than ever. But this doesn’t just create problems for low-wage workers. It is also bad for people with good-paying, high-skilled work, because economies rely on labor of all kinds.

This spatial issue is compounded in cities like ours – which is at the top of the rankings of the top 50 cities for the places where people pay the highest percent of their median household income in transportation (27.3%) – and when major job centers and office parks are located beyond the reach of public transit, as they are here, the inefficiency of the region’s development pattern starts to affect the region’s economy as a whole in a negative way.

In recent years, there have been new partners pledging to attack poverty, but unless plans include strategies to reduce economic segregation, they fail to attack the problem at its core. This answer would not just be an act of morality, charity, or empathy. Most of all, it is an act of enlightened self-interest.

Here are the Data Points on economic segregation for our region:

Large Metros Where the Poor Are Most Segregated:

1. Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis MSA

2. Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford MSA

3. Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington MSA

4. Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor MSA

5. Detroit-Warren-Livonia MSA

6. New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island MSA

7. Buffalo-Niagara Falls MSA

8. Denver-Aurora-Broomfield MSA

9. Baltimore-Towson MSA

10. Memphis MSA

Large Metros Where the Wealthy Are Most Segregated:

1. Memphis MSA

2. Birmingham-Hoover MSA

3. Louisville-Jefferson County MSA

4 San Antonio-New Braufels MSA

5. Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor MSA

6. Detroit-Warren-Livonia MSA

7. Nashville-Davidson-Murfreesboro-Franklin MSA

8. Columbus OH MSA

9. Charlotte-Gastonia-Rock Hill MSA

10. Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach MSA

Large Metros With the Highest Levels of Income Segregation:

1. Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor MSA

2. Detroit-Warren-Livonia MSA

3. Memphis MSA

4. Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis MSA

5. Columbus OH MSA

6. Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington MSA

7. Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale MSA

8. Buffalo-Niagara Falls MSA

9. Kansas City MSA

10 Nashville-Davidson-Murfreesboro-Franklin MSA

Large Metros Where College Graduates Are Most Segregated:

1. Birmingham-Hoover MSA

2. Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown MSA

3. Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana MSA

4. Columbus OH MSA

5. Memphis MSA

6. San Antonio-New Braunfels MS

7. Louisville-Jefferson County MSA

8. Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington MSA

9. Charlotte-Gastonia-Rock Hill MSA

10. Chicago-Joliet-Naperville MSA

Source: Martin Prosperity Institute, University of Toronto

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.

what is “Linguistics Isolation/Dialogue Drift”?

It’s based on a Census definition. Here’s some info from California about it: https://oehha.ca.gov/calenviroscreen/indicator/linguistic-isolation

And here’s an article about it from Anne E. Casey Foundation: https://www.aecf.org/blog/linguistic-isolation-still-a-challenge-for-some-kids-in-immigrant-families/

Its all confirmed in the data. Our local “visionaries” have implemented a culture and a design for decline that hurts all….

Somewhat Related: this shows our economic inferiority complex. We finally got a Trader Joe’s 10 years after Nashville got one and this is what TJ gives out at our grand opening! Also I see they sell Nashville mugs at the Starbucks in our airport! So very Memphis!!!

https://twitter.com/NicTheEditor/status/1040646220144885760

I thought Trader Joe’s explanation about the bags made sense so why get our nose out of joint over something like that. Convenient lack of memory about Ikea which Nashville is still wishing for, but you work to remember everything that can be spun in a negative way. So mature.

To borrow from the words of the Kerner Commission 50 years ago, Memphis is two cities, one black, one white, separate and unequal. White Memphis is enjoying a “renaissance” with growing wealth overwhelmingly concentrated in the white population, a new generation that has rediscovered urban living, and unchallenged segregation based on wealth, income and political control of the suburbs and state. Black Memphis continues to struggle to recover from a housing crisis that gutted the middle class, an economy built on low-wage work with glass ceilings still intact, and the high costs of decades of failing schools, mass incarceration and lack of police accountability. I suggest that people read the book “White Fragility” by Robin DiAngelo to explore why white Memphis — which continues to hold the power and the wealth to control this city — still fails to have the conversation necessary to bring this city together.