Maurice Cox is arguably the most-respected planner in the U.S., and in his Monday presentation in Memphis, he proved why.

It had been 10 years since he was last in Memphis – speaking to the Center City Commission annual meeting on July 9, 2008 – as director of design at the National Endowment to the Arts, and now, working as director of planning and development for the City of Detroit, what was philosophy then is grounded now in clear evidence in Detroit that his approach can turn around a challenged city.

His Monday presentation – “In Search of an Inclusive Comeback Story (Without Easy Answers)” – was a lesson in branding, planning, politics, and project management, drawing clearly on his experience as a City Council member, a mayor, an architecture professor in Italy and America, and now, as a planner.

Most of all, his 217-slide presentation captured an approach that is equal parts pragmatism, perseverance, and pride.

Our Take-aways

Here were our thoughts as we digested his wide-ranging points:

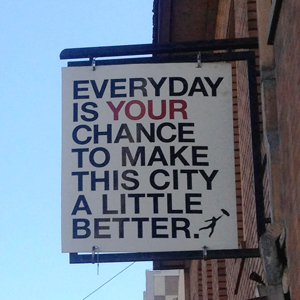

* His planning included an effective lesson in branding, basing it more on reality and a call to arms than clever slogans and a sidestepping of the challenges that everyone knew about.

* The power of a mayor to inspire and galvanize change is an indispensable ingredient in a city comeback, particularly when delivering efficient services in every neighborhood of the city and acting as an active champion for planning.

* The ability to articulate a plan shaped by neighborhoods creates the public’s shared stake in supporting change.

* A vibrant, vital downtown is a necessity for successful cities, but the “soul of any recovery resides in its neighborhoods,” he said. “If you don’t nourish the soul of the city, its heart stops beating.”

* Cities confident in themselves can establish values, principles, and standards that drive development – Detroit has never lost a development because it asks for more from developers.

* There is no substitute for creating a plan that is honored as context for public decisions and investments.

* Local government must be a full funding partner with philanthropy and nonprofits to produce the money needed for short-term impact that signals that real change is under way and the longer-range plan that shows that most neighborhoods will be part of it.

More Points to Ponder

* Aiming high to create the best planning department is key. With $2.5 million from Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan to “reimagine what planning could be,” and recruiting nationally, Mr. Cox grew his department from six planners to 36 people, emphasizing cross-disciplinary knowledge that can spark new thinking and innovative perspectives: architects, planners, landscape architects, and urban designers.

* The preservation ethic of the city administration means that rehab first is the mantra for neighborhoods rather than dropping in inappropriate houses. Detroit is demolishing 100 houses a week – a total of 13,000 so far – and what can’t be demolished is being sold at bargain prices. “We have renovated over 3,000 houses and not built a new single family house because we don’t need them,” he said.

* The riverfront belongs to everybody and design “really, really matters.” The public rallied to the promise that “this is going to be a riverfront for all and putting the first investment in adjacent neighborhoods.”

* Planning must be anchored in community values – inclusionary growth, economic opportunity, and an atmosphere of trust.

Time To Shift Gears

Until about five years ago on this blog, we admonished commenters again and again not to compare Memphis to Detroit, because we had more assets and more options for the future. Also, the comparison was often driven more by racist dog whistles than anything else.

Now, against all odds, we recommend Memphians to look to Detroit to see how a city can turn itself around. These days we can draw inspiration from the way that Detroit has set in place the fundamentals to drive its comeback story, the intentionality behind each decision, and the way the city has mobilized around a challenge to defy all predictions of failure.

“People want to be part of a comeback city,” he said. “People wrote us off but that special kind of grit now propels the work we do.”

There is so much in Detroit that runs parallel to Memphis – the demographics, a data-obsessed mayor determined to create population growth, and an energized cadre of believers who understand that place and economic growth must go hand-in-hand.

It’s The Neighborhoods, Stupid

When he was hired in Detroit, Mr. Cox described it this way: “We can build our capacity to do these more transformative things, which we are poised to do. People recognize that this administration is tending to the business of making this a functional city, and so it sets the foundation and the basis for what I can do, which is to ask them to dream along with us as we try to imagine complete neighborhoods that are places that they can imagine continuing to live, work, and play in for decades to come.”

This singular attention to neighborhoods defines his work in Detroit and becomes a persuasive lesson for Memphis.

Another lesson is the power and importance of a plan – like Memphis 3.0 here – to become the framework for smart decisions about policies and programs. Although Memphis’ comprehensive plan is supposed to be complete in about six months, decisions are being made – from tax freezes for apartments to the future of the long-closed Firestone plant – with disregard to Memphis 3.0.

It’s a sign of concern for the future, because if the plan is to have the impact envisioned for it, it must be valued and respected. That said, it will need strong staff and public advocacy for it because of the risk for politically connected people to have their way in spite of it (think: Unified Development Code).

It there was any question about Detroit’s seriousness about its neighborhoods, it was erased once and for all in May when the successful investment of $42 million in three neighborhoods led city government and partners like the Kresge Foundation to launch a $130 million funding campaign for seven more neighborhoods. The goal: to build 10 vibrant, inclusive areas throughout the city, touching more than 60 individual neighborhoods over the next five years and expanding its scope to include streetscapes, park improvements, commercial development, and housing stabilization.

Getting Honest To Mobilize Change

Where Memphis for more than 10 years has denied it was in crisis, Detroit not only acknowledged it, but acting on the theory that “a crisis is a terrible thing to waste,” it asked for help. That openness about confronting a crisis animated the national conversation about Detroit but put it firmly at the head of the list of cities serious about change. Because of this open honesty about the state of things, Detroit’s resurgence predated Memphis by years when we were losing ground to our peer cities.

That lack of movement created a neediness in Memphis that led it to treat every job as a good job, every development as the right development, and every incentive as a good incentive.

Detroit took a wiser path. “We hold our principles up to developers,” Mr. Cox said, adding that his city has not lost a single project by insisting on its own values and standards.

As for branding, the messaging for the Detroit work speaks convincingly, refreshingly, and honestly about the city. Under the banner of “Detroit Matters,” it is said that “Detroit is BIG, Detroit is BLACK, Detroit is BEAUTIFUL.”

It’s a reality that Memphis and Shelby County have always found difficult to embrace. Mr. Cox proved Monday that it can power new community cohesion and motivation. That’s reason enough to say it loud and say it proud.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.

Detroit has always had so much more going for it than Memphis. The industrial, corporate, higher education, diversity, wealth, airport, and overall economic prowess of the region are huge benefits. Memphis and the mid south are nothing compared to Detroit in spite of its problems. Greater Detroit is also a much better place to do business and live.

Memphis has been in denial about the city’s many huge problems for decades. Far longer than the past 10 years. We have weak leadership at all levels, both govt and private. Unfortunately these weak leaders just try to hold on to their jobs as long as possible and they have successfully run Memphis into the ground. I get sick when I think of how Herenton, Lowery, Wharton and now Strickland have failed. Sad, but Detroit is much better off than here.

I have visited in both Detroit and in Memphis. For me I say to prefer Detroit. Memphis was city with lot of troubles.

thanks anonymous for the constant reminders about how much our city sucks. You should really find a way to move to another city that isn’t so terrible. I’ve lived in several of the “better” cities and i prefer

it here. Glorious Nashville is only 200 miles away, maybe you should try it.

I saw the beginnings of the Detroit Renaissance first hand from 2012-2014 and agree it’s truly inspirational. (Admittedly not having seen Mr Cox’s presentation) It’s hard to understand how you can talk about this transformation without talking about Dan Gilbert. Aside from his shenanigans with Lebron he

– Moved his company (and 3500 Jobs) from the suburbs into downtown

– Has invested ~$5.5B in the city

– Has bought over 100 buildings across the city

– Played an active role in redeveloping, retooling, and relaunching the ddetorit brand

In a city with ridiculously expansive infrastructure (you can fit Boston, San Fran and Manhattan inside the Detroit city limits), Gilbert worked alongside the government to rebuild. Has he been perfect, absolutely not. But Memphis needs a Dan Gilbert equivalent and there are a few people / families in the city who could pull it off (yes, I recognize it’s very easy to spend someone else’s money)

Tom: The Dan Gilbert is well-known and he was pivotal to turning Detroit around, but this was about Maurice Cox’s presentation and he did not mention him.

Appreciate the reply and apologies – thought this was a summary of lessons to learn from Detroit…not lessons from Maurice Fascinating that Maurice didn’t talk about Gilbert at all (but what can you do).

Would love to know what other lessons Memphis can takeaway from Detroit or other cities that have been through turnarounds…

Tom, another turnaround story might be Pittsburgh who has done it more than once. Smart City, I can’t get my arms around how branding around any one demographic promotes diversity. As far as what Eric Robertson and Community Lift is promoting while leveraging the successes in Detroit to support inner City redevelopment, that makes sense to me.

Competitive advantage – and branding – is based on differentiation. We have spent decades trying to obfuscate our most obvious difference when we should have walked toward it. Memphis has always been essentially an African American city – in culture, cuisine, and character. In a world and country becoming increasingly diverse, this can be a strength and our branding should acknowledge it and build on that foundation.

Other cities brand around their Latino culture and others on their ethnic strengths. There is no reason not to do the same with African American culture, but in America, we have a reluctance to state the obvious when it comes to black heritage.

And I would bet Eric would agree with this.

On another note, Memphis has turned around its economy as recently as the 1980s, but we bet too heavily on the thought that nothing would change, a tendency that is seen in today’s denials that logistics is not the promised land we thought it would be. Our history teaches us can turn it around again but we have to be honest in where we are and be bold in our strategies.