In observance of the Memphis Bicentennial in May, 2019, we will feature regular posts about Memphis as it moved toward its founding and the slow progress it made afterwards. Our first chapter was “Native Americans and Fort After Fort” and covered the period from 800 CE to 1809. This second chapter focuses on the role of three Middle Tennessee developers, Andrew Jackson, John Overton, and James Winchester, in carving a town from the wilderness encampment of 50 hearty souls. This is a greatly abridged history and we encourage you to read the many excellent books about the founding of Memphis that can be found in the Benjamin Hooks Central Library

Chapter Two

It turns out that Fort Pickering, the last fort at Memphis, was never a popular posting and there were complaints about the “lawless vending of whiskey and the insolence of the Indians in the absence of a garrison.” It was targeted for decommission by 1811, a year known more for the massive earthquake in December along the New Madrid fault that created Reelfoot Lake. The tremors sent most of the residents of Memphis to the hills, there were reports of the land opening up and shacks falling down. Some said the Great Comet of 1811 months earlier in the year had foretold the disaster.

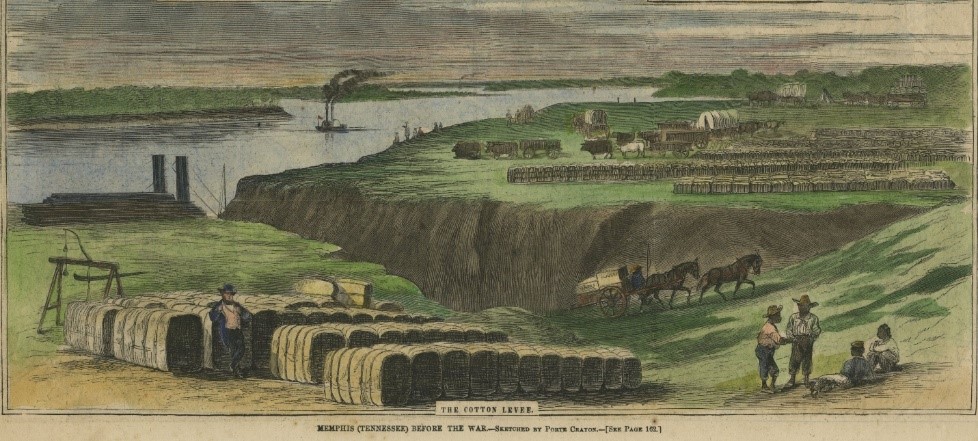

Life at the site at the time was like most similar outposts on the frontier. Activity centered around the fort and the few white settlers traded and intermarried with the Native Americans. There was a little cotton and corn, some hogs and chickens, and trade with passing boats. About the only excitement was when an explorer or traveler came by.

It was not until inveterate land speculators Andrew Jackson, James Winchester, and John Overton set out to lay out a new town that Memphis could be called an actual place. Jackson and Winchester were generals and Overton was retired chief justice of the Supreme Court of Tennessee. Overton and Jackson had partnered on many similar ventures – some of them questionable for the way they mixed their public duties with private profit.

In 1783, in Hillsborough, North Carolina, 5,000 acres adjacent to the Wolf River were recorded for John Rice, a large-scale land speculator who was killed in 1791 by Indians near Clarksville, and a similar amount immediately to the south for John Ramsay. North Carolina – Tennessee was still part of that territory until 1797 – had no right to sell the land because its rightful owners were the Chickasaws, but the rights of native Americans were casually ignored many times as the new nation moved westward.

It’s Just Business

In 1794, Overton bought the Rice acreage for $500, or the equivalent of $10,299 today, and two year later he sold half of it to Jackson, who in turn sold part of his interest to Winchester. By 1819, Overton owned half, James Winchester one-fourth, and Andrew Jackson and the heirs of William Winchester one-eighth each. Ultimately, Jackson sold his interest for $5,000. He had paid $25. In modern terms, the treatment of the native American owners amounted to fraud, but at the time, it was merely common practice. The fact that Jackson was involved in negotiating a treaty that involved land that he owned was done blatantly, and in time, it became a political attack from his foes that did little to tarnish his heroic profile.

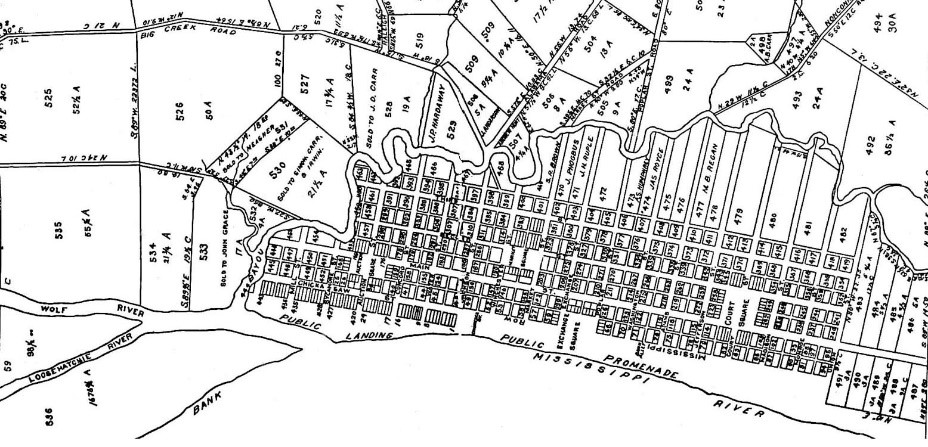

The Rice tract was described as one mile below the mouth of Wolf River with a tongue of land separating the Mississippi River from Wolf River in front of the bluff were the town would be laid out. At the time, the rivers met around where the foot of Jefferson Avenue is today and the Mississippi River struck the bluffs about where Union Avenue is today.

By 1819, the mouth of the Wolf River had retreated to today’s Auction Avenue as a result of Mississippi River erosion. The south boundary went eastward at what is Beale Street today and followed the future Union Avenue four miles to what is now East Parkway, creating a tract of about eight square miles.

By the time Memphis was laid out, Jackson’s skills as a soldier were magnified in heroic stories in which he bested the English and the Spanish; however, his interest in Memphis has been greatly exaggerated. It was a simple business venture like others that his friend Overton brought to him.

If Jackson’s trips down the Mississippi ever involved a stop at the future town of Memphis, it was never recorded, and the images of Overton, Winchester, and Jackson standing atop the bluffs overlooking a mighty river and naming the city Memphis is pure mythology, propelled in modern times no doubt by a diorama at the Pink Palace. The three were never in Memphis at the same time, largely because the route from Nashville was difficult and circuitous, covering 287 miles.

Laying Out A City

The Chickasaw Treaty becomes official on January 7, 1819, and five days later, the three inveterate land speculators agreed to lay out a town site and hired surveyor William Lawrence to do it. He produced one of the first planned communities west of the Alleghenies. It contained 362 lots on the northwest edge of the old Rice tract, laying parallel with the riverfront. None of the three developers planned to live in Memphis so Winchester’s son, Marcus, was sent to act as their sales agent.

The planned town is bounded on the north and east by the curve of Gayoso Bayous. Its plan laid out wide streets running toward the cardinal directions on the compass, with four public squares named for the function envisioned there – Auction, Court, Exchange, and Market. The public landing is planned for Auction Avenue, but because of the mud ruts on the most direct route, wagons were forced onto Winchester. The detour increased the value of Market Square which lay on the route.

Surprisingly, the plan included a spacious 14-acre promenade called Mississippi Row which extended the length of the riverfront along the summit of the bluff and no cuts on the bluff were to be made south of Market Street.

The south boundary of Memphis wasn’t set until 1832 when it only went as far south as Jefferson Avenue. Meanwhile, the Wolf River was so pure that steamboats stopped there to run its water through its boilers. The sparkling Gayoso Bayou has Carolina parakeets and wild swans.

Opposition arose from the handful of squatters who had been living on the bluff for years. Some were veterans of the War of 1812 and others bought their land from the Indians and thought they had a claim to the land. The new owners gave some of them lots to gain their silence, but their hostility continued to the point that Jackson sold his interest in Memphis to run for president.

Florid descriptions of the site were advertised in newspapers, including ones in Cincinnati, Nashville, Louisville, Pittsburgh, and New Orleans. Despite the heavy marketing, the sale of lots for $30 to $100 was discouraging.

The Founding

Once the survey was completed, the first lots were conveyed and temporary titles were issued. It was May 22, 1819, and everafter, this date became the official founding of the city of Memphis.

The first lot was sold to Benjamin Fooy, the most influential and wealthy person in the region. He had moved across the river to Arkansas after the land was no longer controlled by the Spanish for whom he served as local magistrate. He buys lot number 53 at the southeast corner of Winchester and today’s Front Street. It is generally the same place where his house was located when the Spanish were in charge.

After the founding of Memphis, Overton, and Winchester’s attention turns to the creation of a county around it. For a reason that remains unknown, Overton proposed a triangular county, but Winchester wanted one with four sides and it is the one we have today. By November 24, Overton has a petition signed by Memphians and other settlers in this corner of Tennessee that calls for creation of a county, whereupon, the state legislature created Shelby County after separating it from Hardin County (which was only 11 days old at the time). The county was named in honor of Isaac Shelby, Revolutionary War veteran, first governor of Kentucky, but most of all, the commissioner who, with Jackson, “negotiated” the purchase of the land from the Chickasaws.

Its county seat was designated as the Chickasaw Bluffs, but political machinations almost immediately tried to move it. As 1820 dawned, the optimism of the developers had definitely waned. There had been no stampede of people to buy property in the new town, and as the new year began, its population was 53.

For years, the settlement was often described as it was in a Jackson, Tennessee, newspaper in 1824: “the village on the Mississippi better known as Chickasaw Bluffs.”

Next: Defying the Odds