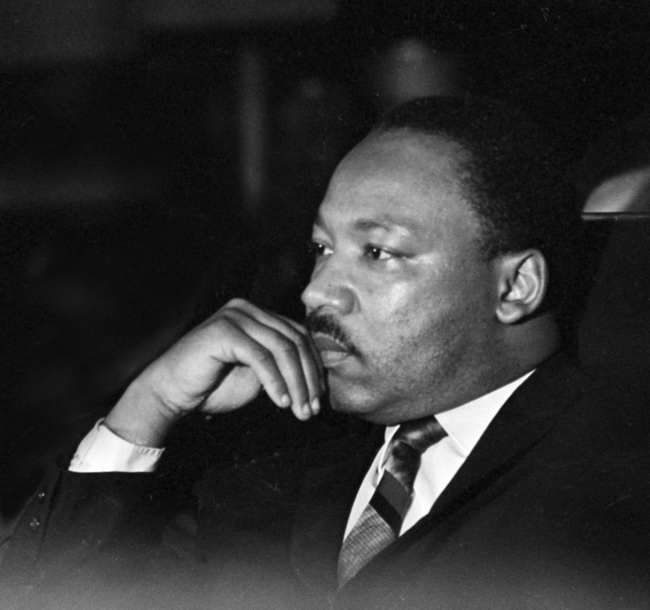

The meeting between Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Memphis Invaders is a footnote in the history of the civil rights giant’s time in Memphis, but it says volumes about him.

Dr. King sent word that he wanted the meeting following his Memphis Sanitation Strike march on March 28, 1968, that turned into a riot in which windows on Main Street businesses were smashed, the Memphis Police Department killed a 16-year-old African American boy in its aftermath, and Dr. King’s leadership and ability to lead a nonprofit protest was called in question.

The reports by the Commercial Appeal – which became notorious for referring to Dr. King as “Chicken a la King” after he was led away from the march by local strike leaders after it burst into violence – and morning daily newspaper and its afternoon sister, the Memphis Press-Scimitar, developed two primary narratives: the violence was caused by lawless, young African Americans and Dr. King was an outside agitator who did not appreciate the strides made in Memphis and could not guarantee a peaceful assembly.

The president of the Memphis Chamber of Commerce moaned that “Negro ministers” should stick to ministering and that “you can’t take these Negro people and make the kind of citizens out of them you’d like.” Memphis’ Republican Congressman Dan Kuykendall said the march had exposed the “evil results of (Dr. King’s) activities.”

The Blame Game

For days after the riot, the news media and most of the white leadership structure hammered home the message that the problem did not lie in the unfair policies directed at sanitation workers but in union organizers, out-of-town protest leaders, and ungrateful sanitation workers. About all that was missing – just barely – was calling them “uppity.”

The narrative about the cause of the riot relatively quickly turned to the Memphis Invaders, the city’s local version of the Black Panthers. They became easy scapegoats for the blame, and mainstream civil rights leaders were quick to point the finger at them, leaving some of Dr. King’s associates were furious with them as a result.

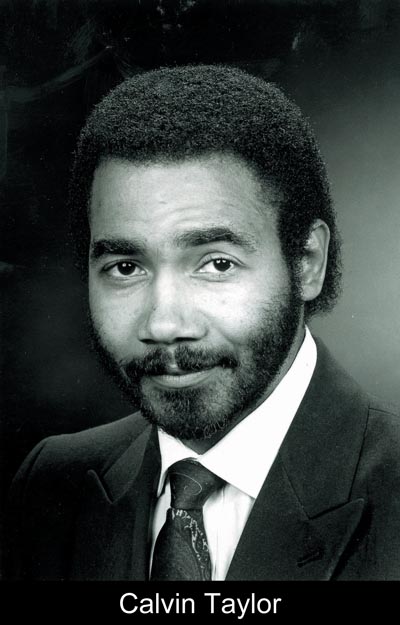

And yet, Dr. King wanted to meet them, and the day after the failed march, Charles Cabbage, Calvin Taylor, and Lorenzo Childress were ushered quietly into the Holiday Inn-Rivermont (now the Rivermark Apartments at 655 Riverside Drive) to meet with Dr. King. Dr. King would later move to the Lorraine Motel where he had stayed several times previously, and we have memories of harangues by the media and some white officials that he was a hypocrite for not staying at a minority-owned motel. “It was a smear tactic,” said Mr. Taylor. “The white media forced him out of the Rivermont after making the case that he didn’t really care about poor black people.”

At the time, Mr. Taylor was working as a reporter at The Commercial Appeal but his bosses were unaware of his role as a founder of the Invaders, and as a result, it surprised everyone at the newspaper when a photo taken by the Memphis Press-Scimitar showed him walking into Dr. King’s room overlooking the Mississippi River.

The Big Question

Mr. Taylor – a dear friend – and his fellow Invaders were greeted frostily by Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, a close friend of Dr. King and co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Dr. King’s associates appeared surprised that the Invaders were even willing to meet, said Mr. Taylor, adding that Dr. King’s first question was about the breakdown of the march.

“We said, ‘what makes you think we messed up the march?’” said Mr. Taylor. The Invaders’ tempers flared, and motivated by their black empowerment philosophy, they were cynical about the cause of the riot.

Mr. Taylor recollected: “His march was messed up from the beginning. He wanted one million African Americans to come to Washington (for the Poor People’s Campaign focusing on economic justice for poor people in the United States). They wanted an excuse not to allow it. There were black and white people out to mess it (the Memphis march) up. It was a riot because someone wanted to have a riot that day.”

Dr. King had attended Morehouse College with Mr. Cabbage so the conversation turned to reminiscences about those days. “They were just two Morehouse boys talking,” said Mr. Taylor, adding that the Invaders were jaded about the impact of the War on Poverty and were advocating – some said agitating – in Memphis for better schools, better jobs, and the end of mass incarceration for African Americans.

Double Lives

The Invaders – largely pictured by the media and police as out-of-control young African American thugs from the ghetto – were in truth college graduates who had given long and serious thought to the struggle for equal rights and economic justice in America. The group was regularly harassed by law enforcement because of their obvious resemblance to the Black Panther Party with their black berets and leather jackets.

They took their name from the popular science fiction television program of the day, The Invaders, about a secret alien invasion in which people who were normal looking Americans by day were aliens in their meetings by night. It reflects the way the group saw themselves, as proven by Mr. Taylor’s reporter by day and militant by night persona.

The early leaders were Coby Smith, honors student and one of the first two black students at Rhodes College; Charles Cabbage, a Morehouse College political science graduate; John Smith, military veteran and intellectual; and Mr. Taylor, University of Memphis journalism graduate. They debated political philosophies and quoted with ease the Bible, Gandhi, Cleaver, Mao, and the U.S. Constitution.

Looking back and recalling the forces arrayed against them and their calm demeanors over the years in recounting their stories, it’s hard to fathom a time when their names prompted fear and anger, a time when they were blamed for everything that happened in the black community – from school walkouts to bank robberies.

Yin And Yang

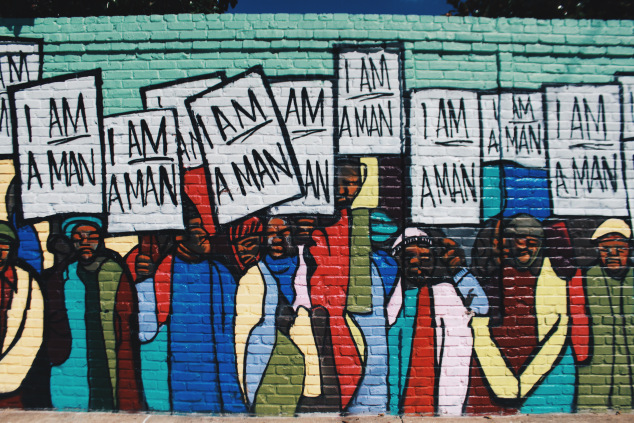

While mainstream civil rights leaders concentrated on settling the strike, the Invaders called for more self-determination by African-Americans, more disruption of the status quo, and a new black consciousness and pride. As a result, their military jackets and their berets became symbols of grassroots anarchy, and they were rejected by much of the African-American leadership.

In this way, if they had not existed, the Memphis civil rights movement would have invented them. They were the militant yin to the mainstream movement’s yang. They were the tough talk to the leaders’ persuasive rhetoric. They were the grassroots organizers to the movement’s leaders.

But, most of all, they created a palpable fear in Memphis that kept white power brokers at the table talking to civil rights leaders that were seen as more reasonable and less volatile. Because the vocabulary and the actions of the Invaders was about Black Power, the demands of civil rights leaders seemed moderate and reasonable in comparison.

This was the backdrop to the meeting with Dr. King that most well-known Memphis civil rights leaders would have found objectionable if they had known about it. And yet, Dr. King talked with them about their agenda, their priorities, and what they needed to succeed. Mr. Taylor said they described their program of action and he asked them to prepare a budget for making it happen and bring it back to him. That did not happen because Dr. King was called out of Memphis and returned to Memphis shortly before his death.

A Man Of Peace

Dr. King’s calm attitude likely shocked the members of his entourage in the room, who were accusing the Invaders of being culpable for the riot, but Dr. King said it didn’t matter who was responsible; what mattered was having a peaceful follow-up march on April 8, 1968.

He said that the Memphis march leaders should have met with the Invaders before the March 28 march because they were “out there working” and then asked them to serve as security for the next march. Against all odds, they agreed to Dr. King’s request and agreed to help develop a plan to keep the peace.

When Dr. King returned to Memphis five days later, he moved the Invaders into the Lorraine Motel with him, a decision that infuriated some of his colleagues. Whether Dr. King recognized the value of grassroots involvement or whether he wanted the Invaders where he could watch them, he had the innate ability to bring disparate contingents into the fold.

Looking back five decades to those days, Mr. Taylor said of Dr. King: “He had an aura about him. He was the epitome of a nonviolent individual. He never raised his voice. There was no change in his demeanor. He couldn’t believe the black leadership in Memphis had never listened to us. He had a genuine desire to help people. Some say that he came here because of his friendship with James Lawson, but after he got here, he understood that the sanitation workers were the lowest of the poor people in American, earning 55 cents an hour, and it struck a chord with him because that was at the heart of who he was.”

Everything Changed

On April 4, only a couple of hours before a single bullet struck Dr. King in the neck and chin, severing his spinal cord, the Invaders were asked to leave the Lorraine Motel following an argument with leaders of Dr. King’s camp. Shortly after arriving at their South Memphis apartments, they would learn that Dr. King had been fatally shot. Mr. Taylor would learn about it by reading it on the teletype machine clattering at The Commercial Appeal.

In the wake of the shooting, an APB was issued that a person driving a Mustang had fled the scene. The Invaders drove a similar Mustang, and after being stalked by the Memphis Police Department got weeks and infiltrated by an undercover agent of the FBI (who later moved to the CIA), they can be forgiven for their initial fears that they were being set up.

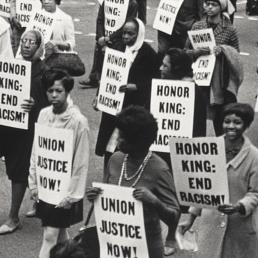

Four days later, on April 8, the massive march envisioned by Dr. King took place and stretched nine blocks from City Hall to Main and Linden and around the corner. But this time, it was a Memorial March in honor of Dr. King himself. Estimates were that 40,000 marched, including Coretta Scott King and the King children, celebrities, union officials, bishops, and rabbis, but most of the crowd were tens of thousands of African American Memphians.

Keeping their promise to Dr. King, the Invaders moved along beside the march, keeping order and handling security on the saddest day in Memphis history.

Eight days later, Memphis City Council adopted the memorandum of understanding as city policy. The union had won everything they were asking for and the next day, April 17, sanitation workers went back to work.

It is devastating to read the many news stories and social media posts of how Memphis has become a poorer and even more racially divided city over the past 50 years.

There is global attention on Memphis this week. I’ve yet to see or read anything really positive our encouraging about this city and it’s current state or future.

From the New York Times, April 2, 2018

The Triumphs and Trials of Memphis

“A city with little luster left to lose”

https://nyti.ms/2GrPqzW