So, now what?

We’ve been waiting for years for this past week to come, and now it’s in the rear view mirror.

So, the question before us is what we’re going to make of it: congratulate ourselves for some impressive ceremonies and events, proudly post the selfies we took with celebrities and notables, conjure up personal memories of 1968 and the years after, or find inspiration from the calls to arms.

Essentially, do we return to business as usual or do we find it in ourselves to pivot as a community to a more urgent agenda for change?

Time will tell, but if the last week wasn’t enough to convince us that we have to do more, we are sleepwalking toward the future.

Case Study For Lack Of Progress

There has never been a time in the history of Memphis when there were more giants of the movement – intellectuals, activists, luminaries, legends, religious leaders, unionists, strategists, and King family members – in the city than there were for MLK50.

The overriding message from the week is the lack of fundamental progress in the United States despite the façade of racial equality. Along the way, some commentators treated Memphis as a case study for the lack of progress in opportunity and prosperity since 1968.

Here, we have a Memphis-centric focus, but we never lose sight of the fact that the depth of problems in Memphis have causes rooted deeply in national policies that limited wealth creation among African Americans and the lack of federal programs that dealt with the underlying causes of poverty rather than just addressing its symptoms.

We’ve written for 13 years about the serious challenges facing Memphis, and unfortunately, in that time, few of the key economic measurements and economic justice indicators have improved. For those of us who lived and suffered through the murder of Dr. King, it is difficult to understand – and accept – that so much remains to be done despite his sacrifice five decades ago.

Déjà Vu All Over Again

All in all, most national media concentrated last week on the speakers and a recounting by eyewitnesses to the sanitation strike and Dr. King’s murder, but when they did venture beyond the official program and the sites of the ceremonies, they described at best, a city that has made little progress, and at worse, a city in crisis.

All in all, it feels familiar.

In the wake of the assassination, the cruelest cut was delivered by Time magazine, which described Memphis as a “decaying backwater river town.” If there was anything positive that grew out of this brutal assessment of our community, it was that the smack down that deflated community pride already laid low by Dr. King’s murder and its own malaise helped to drive some people a few years later to fight for downtown’s future, to revive the Peabody Hotel and Beale Street, to start publication of Memphis magazine, to create Memphis in May International Festival, to fund the building of Mud Island, and more.

The sting of the Time magazine comment lingered when critics of the funding for Mud Island were met with a one-page advertisement in The Commercial Appeal that said: “Don’t let a few pessimists keep Memphis in the backwater.”

Looking back, there’s no argument that the initiatives that began to improve and reposition Memphis following the assassination were important, but there was not as much attention paid to addressing the poverty and lack of economic justice that brought Dr. King to Memphis in the first place.

Little Luster

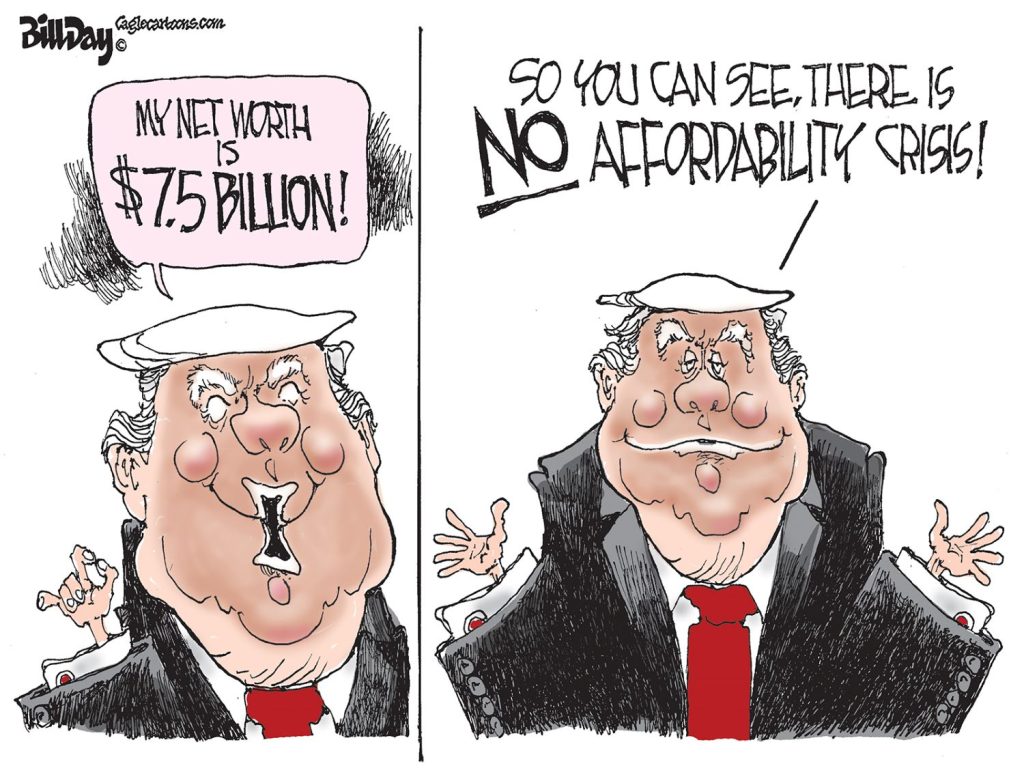

That inattention – which so often leads us to do the same and expect different results, such as issuing tax freezes that shift money from average Memphians to major corporations but don’t have any significant impact on improving median incomes – produced the 2018 version of the ”backwater river town” criticism when the New York Times wrote that Memphis, “a year shy of its bicentennial, feels like a place with little luster left to lose.”

It’s tempting to say that the journalistic dig is a real wake-up call, but there have been too many of those over the past 15-20 years.

In the end, one thing we learned last week is that our talk about mythic music, the artistic freedom found here, and the rich vein of entrepreneurship did nothing to mask the truth from these reporters.

That should be a lesson for us as some say what we need here is simply better marketing of the city. As we have written before, it’s not that we have to tell our story better. Rather, we need a better story to tell.

Memphis As Measurement

And just to be sure we understood its point, the New York Times added: “In concrete ways, and in far more subtle ones, Memphis is inexorably tied to Dr. King, and more than any other city, it is perceived as a place to measure the progress of Dr. King’s legacy and dreams. But in the half-century since Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis during his peaceful crusade against pauperism and racism, the city has been immersed in poverty, segregation and violence. Its triumphs are never far from its trials.

“In the beginning, Memphis seemed a worthy steward of the King legacy, swiftly electing the first African-American to represent Tennessee in Congress. In 1991, the city elected its first black mayor…But black financial success has never come close to matching that of politics, and Dr. King’s fight against poverty is a battle that Memphis has so far lost.”

The nation’s leading daily newspaper also said that the number of murders in Memphis is higher than much larger cities like Boston, Dallas, Denver, San Francisco, and Seattle…The gulf between rich and poor is gaping. The streets can feel desolate and forgotten, a certain sadness stretching block after block.”

And while the New York Times’ blunt observations were matched by some other national media outlets, those weren’t the most important critiques we should listen to. Rather, it’s the real experts of Memphis – the people who live in the city and care deeply about its future.

The Experts

One effect of MLK50 that had the most impact for us was to compress many expressions of tough love from our own African American leaders. It’s not that they hadn’t made similar comments before, but when heard as a collective spread over a concentrated period of time, they were speaking through a megaphone.

Otis Sanford, professor at University of Memphis and commentator for Channel 24: “It’s a malaise here. There is neither optimism nor strong pessimism, honestly. We’re just sort of standing still right now.”

Brad Watkins, executive director of Mid-South Peace and Justice Center: “We are expected to embrace a fairy tale of false positivity. The data is shocking, but it is data that we know. We know what our lyin’ eyes tell us. We have policy that is more interested in cheerleading and big projects and grand sweeping gestures and taking credit for other government sources forsaking its real responsibilities. We have to speak out for truth.”

Kenneth Robinson, president/CEO of United Way of the Mid-South: “It’s the story of a city that’s stuck. Fifty years later, we are still stuck. The data supports the fact that we are stuck. That’s not a good place to be, considering all the other advancements we have celebrated in this city. To be able to walk through our community and see an African American child and see what we have a binary choice: poor or not. We are stuck. The data compels us to tell the rest of the story. How do we get unstuck? It is one thing to talk about the historical story and institutional issues that kept African Americans behind, but the rest of the story is, where do we go from here?”

Wendi Thomas, founder, editor, and publisher of MLK50: “Poverty persists because somebody profits from it. I hear people say the system is broken, but the system is not broken. It is doing exactly what it was designed to do. Until we look at who benefits from other people’s discomfort and are willing to sit in that discomfort and ask tough questions about what it would look like to have the radical redistribution of resources King talked about.”

Stacy Spencer, senior pastor of New Direction Christian Church: “I see a rising tide of hopelessness. Our young people are drowning in hopelessness. When you have no hope, you have no regret. Proverbs 13:12 says hope deferred makes the heart sick. We have a sick city and a system that no longer benefits its people. We tell our young people to try harder, study harder, work harder, yet the rewards don’t match the work and then we wonder why millennials are making an exit, leaving a frustrated older population who don’t understand why young people won’t stay at home. We keep telling young people to pull themselves up by their bootstraps when people keep taking their boots.”

The Magic

There were many others, and the willingness to talk straight was a gift during MLK50 and a challenge to our community. The question now is, how does Memphis answer them. Does it respond with happy talk about billions of dollars of construction projects? Does it default to talking points that essentially ignore what we are being told? Does it drown out their criticisms with comments that are nonresponsive and patronizing?

There are no magic answers.

There is only the magic that comes from a community united to change its own future.

MLK50 reminds us of many things, including the power of one person to change the world, but even more, it reminds us that collectively we have an obligation to fight for those who are powerless, to speak for the voiceless whose words are drowned out by marketing statements, and to act in our own mutual self-interest to once and for all refuse to write off any member of the community simply because of where they live, what color they are, or how much they earn.

That’s the lesson of Dr. King’s life and death, and we don’t have 50 more years to get it right.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

MLK’s remarks about poverty are still valid as there where 50 years ago.

Not much has changed since then.

Memphis is stuck in a rut for a very long time. There are some signs that things might get a little bit better. But I am not crazy optimistic about that.

Memphis is not worthy of any part of the King legacy.

TIME magazine’s calling Memphis “a decaying backwater river town” is still entirely accurate. In many ways the city is worse off today than in 1968.

Memphis today truly “is a city with little luster left to lose.”