In light of White House Chief of Staff John Kelly’s recitation of neo-Confederate mythology about Robert E. Lee and the cause of Civil War, we’re posting an article we wrote for MLK50.com about how the Myth of the Lost Cause – from which Mr. Kelly drew his mangled understanding of history – played out in Memphis. (Thanks to Wendi Thomas for suggesting this article and previously publishing it at MLK50.com.)

A direct line runs from the myth of the Lost Cause to the reality of lost opportunity in much of the Deep South.

To understand this, you only need to compare a map of the slave states of the Old South at the time of the Civil War to present-day maps that show America’s most entrenched poverty, low educational attainment, poorest health outcomes and sputtering economies. The maps are almost identical, illustrating how clinging to romanticized notions of Confederate heritage in the Deep South Confederate states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina and Texas — later joined by Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia — led to an economy dependent on worker exploitation, low wages and low government investment in human capital.

The 2014 U.S. Census shows the South has the highest percent of population living in poverty of all regions — 17 percent; the highest percent of adults reporting fair or poor health — 20 percent; highest rate of infant mortality — 6.7 deaths per 1,000 live births; and lowest educational attainment, with 10 states of the Confederacy finishing among the bottom 18 states in high school graduation. In rankings of the 50 largest metro areas, the Memphis Metropolitan Statistical Area persistently ranks in the bottom in these same indicators.

The maps make a persuasive case that the Lost Cause has been a drag on the former Confederate states: The willful twisting of historical fact shaped economic decisions that still cost the South opportunity and prosperity today, when success is defined by high-skilled, highly educated workers in an infrastructure that connects cities to a global marketplace.

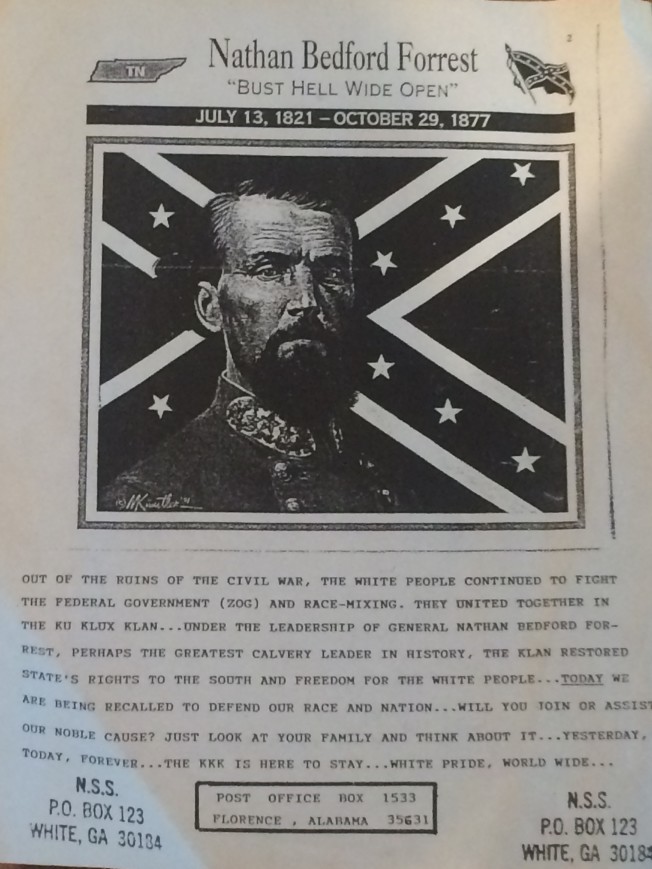

And yet, the revisionists persist, like the Sons of Confederate Veterans, which held its “reunion gathering” in Memphis July 18–23 aimed at “insuring (sic) that a true history of the 1861–1865 period is preserved for future generations.” It’s a place where the false history about the antebellum South features stories about state’s rights, chivalry and heroism, happy and faithful slaves treated as members of the family, and stoic Southern women who sacrificed their loved ones to the cause of liberty and freedom, all while explaining away the racism memorialized in statues like those of Nathan Bedford Forrest and Jefferson Davis.

If the Lost Causers were merely confederates in rewriting American history, it would be easy to dismiss them as sound and fury signifying nothing; however, their attitudes and beliefs for 150 years have perpetuated discrimination, marginalized African Americans, deprived equal rights and built an economy predicated on low-skill workers.

Twisted History

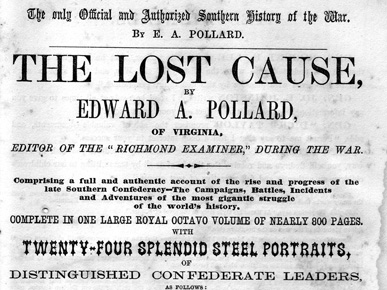

This distortion of history was embraced and propelled by Hollywood, beginning with the heroic portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915’s Birth of a Nation and continuing with dozens of films into the 1970s built around sympathetic portrayals of noble former Confederate soldiers. It was a theme powered by 1936 best seller, Gone With the Wind, which won a Pulitzer Prize and became an influential movie in 1939 that won eight Academy Awards, including best picture. As popular culture advanced the Lost Cause narrative, Hollywood consistently ignored the horrors of slavery and pretended that the forced labor of millions of men and women was just a footnote, instead of the primary cause, that led to the South’s secession from the Union.

Neo-Confederates sentimentalize the stories and assert that it was economic and cultural issues that drove the Confederate states out of the Union, but all of the arguments lead to the same place: Preserving slavery was the motivating issue for secession and war. Any other reading of history is disingenuous, deceitful and odious.

In time, it was not considered genteel in the South to defend slavery, so it had to be explained in other ways — ways like heroism. The Lost Cause became the force behind the instruments of white supremacy, expressed by the naming of parks and streets and the erection of statues and monuments honoring heroes of the Confederacy.

The message to African Americans was unequivocal: We may not have won the war, but we will not abandon the core beliefs that sent us to battle.

The Lost Causers saw the Confederacy as engaged in a noble cause and African Americans as a necessary evil required to support a commodities economy focused on selling products at the lowest price and paying workers as little as possible. Slaves possessed nothing and after the Civil War, former slaves had little more, but what they did have was prey for the “company store.” They were sometimes paid by “scrip” that was only redeemable at the company store, where costs were inflated along with interest rates. What land former slaves had was often taken to pay debts to the store. It was “slavery by another name.”

As an alternative to the fields and fealty, Memphis offered the prospect of “city work” although jobs for African Americans were normally menial and low-paying, accompanied by the persistent message that “they” should “stay in their place,” another Lost Cause meme. If the Confederate veterans marching through the streets and parks named in their honor were not enough to underscore this message, there were lynchings that continued well into the 20th century (with one as late as 1939), often accompanied by modest, if any, newspaper coverage.

The present silence about the Lost Cause movement in Memphis suggests that the city was immune to the message from groups like the Sons and Daughters of the Confederacy, but there is a direct connection between the Lost Cause and the relocation of the grave and construction of a statue of slave trader, Ku Klux Klan founder and Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. It moved from historic Elmwood Cemetery to a prominent park on a major city street and the dedication in 1905 was attended by 30,000 people. Forrest’s 8-year-old granddaughter unveiled the statue while the band played “Dixie.”

It was a major civic event in Memphis — at least for whites. For African Americans, it was a potent reminder that while Beale Street might be tolerated, they lived in a community where lynchings — a formidable form of community control — were not uncommon, where the offices of anti-lynching journalist Ida B. Wells were destroyed before she was ultimately forced to flee the city for her life, and where their limited opportunities were laced with subservience and obsequiousness.

20th Century Confederates

Nathan Bedford Forrest died in 1887 and 10 years after his death, with the turn of a new century approaching, a fundraising campaign headed by former Confederate officers was mounted in Memphis to erect a statue in his honor. Meetings of the Forrest Monument Association featured competitions between Confederate veterans’ drill teams.

To accentuate the city’s Confederate pride, the statue’s cornerstone was laid as part of the 11th annual national reunion of the United Confederate Veterans in Memphis in 1901. The city was festooned with 15,000 Confederate flags and bunting and parades by 15,000 Confederate veterans with their ribbons, medals and banners. A temporary “Confederate Hall” for 18,000 people was built in Confederate Park for the celebration and razed after the reunion.

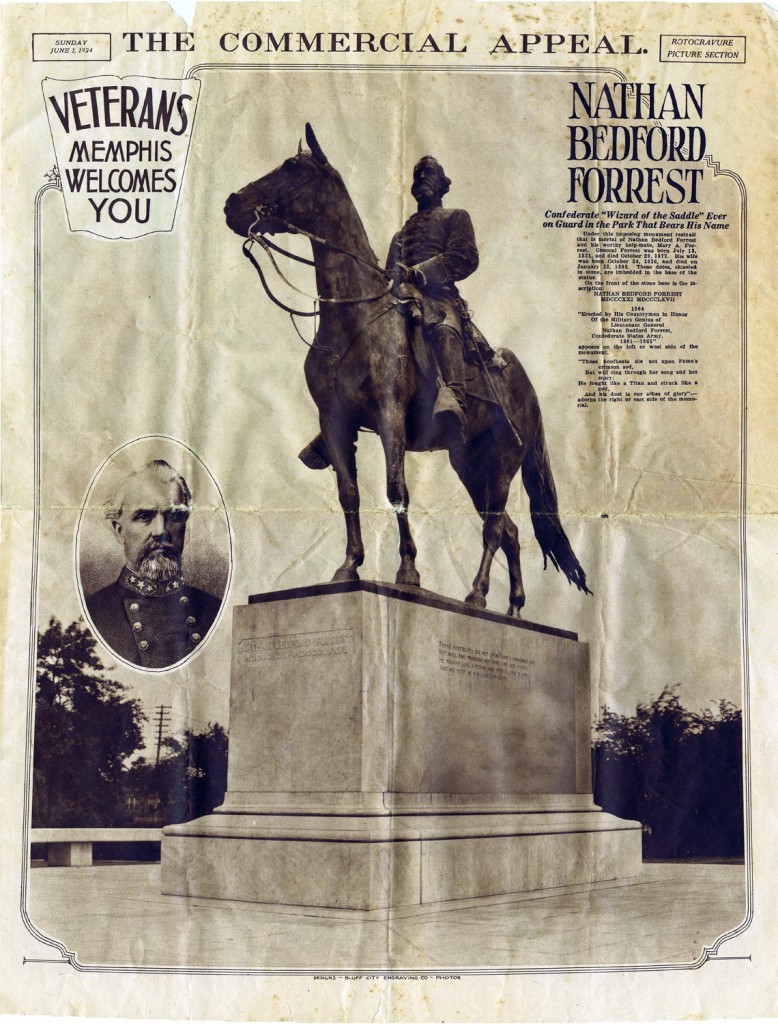

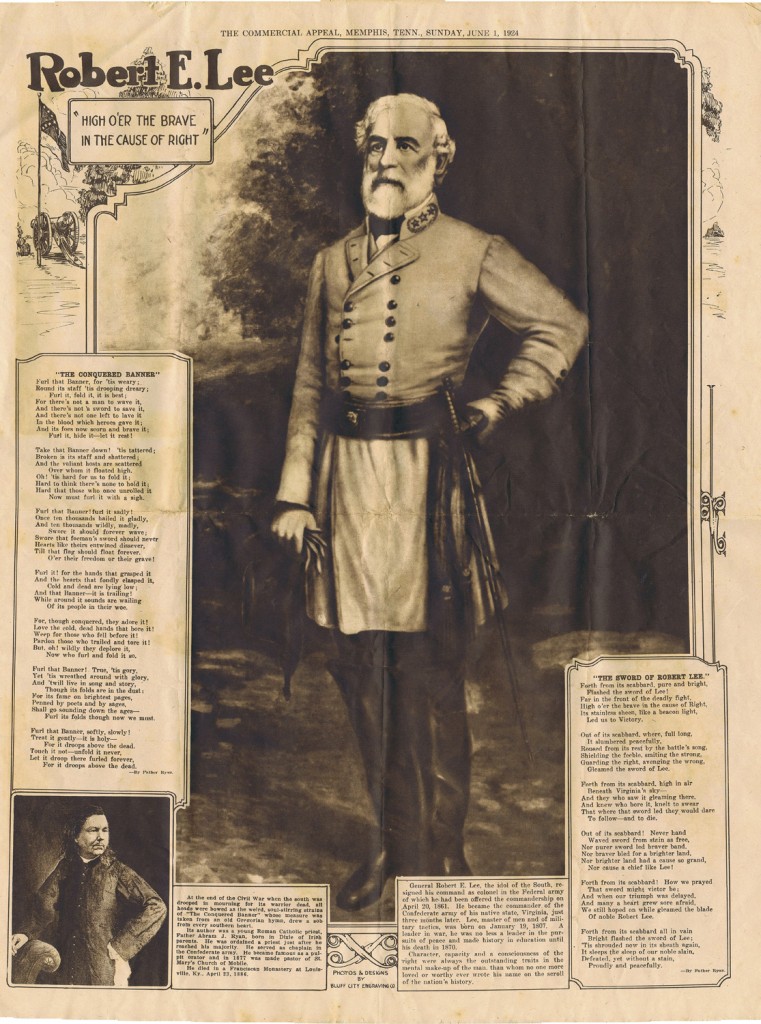

Other national reunions for the Rebel soldiers were held in Memphis in 1909 and in 1924. For the 1924 gathering, the Memphis newspaper The Commercial Appeal published an eight-page commemorative edition, Veterans: Memphis Welcomes You, with a front page consumed by a photo of the Forrest statue and the caption: “Confederate ‘Wizard of the Saddle’ Ever on Guard in the Park that Bears His Name.”

Other pages in the special edition honored Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee — “high o’er the brave in the cause of right” — and etchings of battles that even included the naval battle at Memphis (without any context that it was hardly the Confederacy’s finest hour). There were etchings of other officers with sentimentalized captions like the one that said some had gone on to “fame’s eternal camping ground.” The welcome from the Memphis chairman of the event emphasized that the former soldiers were “in the heart of the Confederacy, the home of General Nathan Bedford Forrest and of President Jefferson Davis.”

The celebrations overlooked the fact that Memphis was largely unscathed by the Civil War and was under Union control for most of it. Both “Battles of Memphis” were embarrassing disasters for the Confederacy. The first was one of the briefest naval battles in history, lasting about two hours in the early morning of June 5, 1862, and witnessed by thousands of Memphians who watched from the river bluff in a carnival atmosphere. By noon that day, after essentially destroying the Confederate presence on the Mississippi River, federal forces took charge of Memphis.

The second Battle of Memphis on August 21, 1864, at 4 a.m. was equally unimpressive and lasted only a few hours. It consisted of a raid by Forrest that achieved none of its military objectives. Its primary result was that it led to the Union beefing up its forces in Memphis until military rule ended on July 3, 1865. The event left few marks on Memphis, but inspired yet another bit of Lost Cause graffiti when an alley in downtown Memphis was named General Washburn’s Escape Alley in honor of Forrest forcing Union Major Gen. Cadwallader C. Washburn from his home wearing only his nightshirt to take refuge in a nearby Fort Pickering.

Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant took command of Memphis for a short time, and, after observing the smuggling carried out in the city, he said the disloyalty of Memphians to the Rebel cause was striking. That Memphis enthusiastically joined into the Lost Cause movement with such a dubious Civil War history hints at the depth of emotional support for it that existed in the heart of the Deep South.

Resurrecting the “Forgotten Man”

An alliance between political boss Edward H. Crump, a white Democrat, and Bob Church, African-American Republican, controlled Memphis politics in the 1920s, but in the late 1930s, it ended with Crump’s betrayal and the destruction of Church politically and financially. Without Republicans in the White House, Crump no longer needed Church, accusing him of creating racial division and telling the Memphis World: “You have a bunch of niggers teaching social equality, stirring up racial hatred. I am not going to stand for it. I’ve dealt with niggers all my life and I know how to treat them…. This is Memphis.”

In 1956, with the centennial of the Civil War approaching, a fundraising drive was launched to honor the “forgotten man,” President of the Confederate States of America Jefferson Davis, who lived in the former Peabody Hotel for several years in the 1870s while working as president of a life insurance company. “Memphis is the only major city in the South that does not have a statue of this great man,” said the fundraising leader. Notably, before he died in 1954, Boss Crump put his stamp of approval on the plan and the Memphis Press-Scimitar, the afternoon daily newspaper, chronicled the fundraising drive for eight years.

For most of its life, Confederate Park (renamed Memphis Park in 2013) was uncluttered. A 1940 photo publication, “Memphis in Pictures,” shows a park free of a statue, cannons and the other Confederate dross that now populates the park. Signs of the times were seen in the publication: The only photos of African Americans show them waiting to be processed at the Memphis Police Department and a handsome, young black boy on the back page is featured above the caption: “Memphis sho’ am a swell place to live in.” It was reminiscent of “Hambone’s Meditations,” observations about the world by an African-American man caricatured in the one-panel cartoons of J.P. Alley on the front page of The Commercial Appeal from 1916 to 1968 with captions like “Sho is heap o’ hol’-ups roun’ heah — co’se ain’ no-body hilt me up yit, but dey neah bout runs me to death some times.” (Although the newspaper won a Pulitzer Prize in 1923 for editorializing against a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, that is not to say it was a champion for equal rights for African Americans.)

In this context, the erection of Davis’ statue delivered a prime Lost Cause message: We will never forget that our city is part of the Old South. The engraving on the statue says: “He was a true American patriot.” The base states that it was erected by the Jefferson Davis Memorial Association, United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, the Children of the Confederacy and Patriotic Citizens, groups which included members of some of Memphis’ most prominent white families, such as the wives of Harry Allen and Charles Crump, Lottie Blount, St. John Waddell, Byron Hyde, John Apperson, and Walter Chandler, former Memphis mayor, former Congress member and adopted father of Wyeth Chandler, who followed Henry Loeb to the Memphis mayor’s office in 1972.

The monument does not include any of the “forgotten man’s” quotes from numerous speeches setting out his ideas about the inferiority of African Americans, but it did not need to. Davis’ beliefs were for his race a commonly accepted mishmash of Christian salvation and Southern benevolence to justify slavery, an approach prevalent in the South well into the 20th century. Davis said African Americans were “gathered from the torrid plains and malarial swamps of inhospitable Africa … untaught in all the useful arts and occupations, reared in heathen darkness, they were transferred to shores enlightened by the rays of Christianity. There, put to servitude, they were trained in the gentle arts of peace and order and civilization; they increased from a few unprofitable savages to millions of efficient Christian laborers … their strong local and personal attachment secured faithful service to those to whom their service or labor was due … never was there happier dependence of labor and capital on each other. The tempter came, like the serpent in Eden, and decoyed them with the magic word, ‘freedom.’”

The dedication of the statue October 4, 1964, was clearly meant to portray a parallel universe in Memphis at the same time the civil rights movement was striking at the foundation of the Lost Cause: segregation.

Clearly, Memphis was on the wrong side of history.

Three months before the statue dedication, the U.S. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, and two months earlier, the bodies of young civil rights workersAndrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney were found in an earthen dam 190 miles south of Memphis. Ten days after the Davis statue was erected, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. received the Nobel Prize for Peace, four years before he would be murdered in Memphis as he led protests in support of better working conditions and wages for African-American city sanitation workers.

In 1968, following the murder of Dr. King, Memphis worked hard to down play the Lost Cause attitudes and anti-union and “separate and equal” sentiments in Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb’s office that provoked the strike by African-American sanitation workers, who were seen through a long-established lens as low-status workers. At the time, the average pay for sanitation workers was the minimum wage of $1.60 an hour. As a result, 40 percent of them qualified for welfare. Loeb, whose workforce at his family businesses was largely African American and powerless to negotiate better salaries, stonewalled the pleas of the sanitation workers following a long-standing Southern principle: African Americans could never be allowed to challenge the white power structure.

Memphis Workers Discounted

Ultimately the sanitation workers won the right to unionize and were promised a better wage, but the thinking of the past had already shaped economic policies that sold Memphis for its cheapness, especially when it came to labor costs, rewarding the men at the top and keeping a permanent underclass to suppress wages. These decisions have put modern Memphis at a serious competitive disadvantage in an economy that places a premium on innovation and technology by highly-skilled and well-paid workers.

In early July, the Memphis City Council, at the recommendation of Mayor Jim Strickland, approved payments of $50,000 each for the 14 living strikers and increased the City of Memphis contribution to sanitation workers’ 401(k) retirement accounts, resulting in a bump of between 1.5 and 4.5 percent in earnings.

About 25 years ago, when Memphis and Shelby County created the Industrial Development Board to hand out tax waivers through PILOTs (payment-in-lieu-of-taxes), the justification for the program was that it was needed in the near term because of the low quality of the Memphis workforce. It was said that workforce training would change things and tax waivers would then no longer be needed.

And yet, today, with about $70 million in PILOTs approved every year, the workforce is still said to be low-skill, provoking a Whitehaven resident to say during a 2013 City of Memphis public meeting about its five-year fiscal plan that it proves once again that “the rich get richer and the poor get poorer and that white folks always come out on top.”

That summed up well the working philosophy of an economic system built on forced labor, whose Lost Cause principles insinuated themselves into the post-Civil War South through policies that created and perpetuated disparities in income and opportunities between the races. Because of it, the monuments in Memphis parks not only pay tribute to Confederates who led a rebellion against the United States, but they also pay tribute to a philosophy that has held back progress in the South for 150 years.

The Sons of Confederate Veterans often repeat their talking point that we should not rewrite history by removing the monuments, but that begs the question as to why the history wasn’t written right in the first place.

After all, they don’t call for more complete histories of Memphis when it comes to African Americans or for statues that memorialize fearless anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells; Ed Shaw, target of the Ku Klux Klan in 1868, elected to City Council in 1873 and wharfmaster in 1874, making him the highest paid official at the time; or Joseph Harris, the first African American to own property (after first buying his wife and baby daughter). There are many, many more.

These are the real Memphis heroes — courageous, principled, and inspirational — and they represent the values of modern Memphis.

But the neo-Confederates are only interested in the warped history of the Lost Cause, which was embraced by the Tennessee Legislature when it passed the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act of 2013 to prevent Memphis from removing the Confederate statues from city-owned parks.

Lead sponsor for the law was Republican Rep. Steve McDaniel, who lists “Southern historic preservation” as an interest on his legislative website. He is historian for the Parkers Crossroads Battlefield Association, which commemorates a battle in which Forrest narrowly evaded capture. He lives in Parkers Crossroads, 111 miles northeast of Memphis, and from his town of 330 people — 81 percent of them white — he used his state office to mandate his Confederacy delusions on a majority African-American city of 652,717.

It just proves how alive and well the myth of the Lost Cause remains in our region, where its chief victims today continue to be history itself, a city working to move beyond a past of lost opportunity, and the 63.3 percent of Memphians who are African Americans and still subjected to symbols of racism on publicly-owned land as part of their daily lives.

The only word to describe Forrest, Davis, Lee or any other Confederate leaders is TRAITOR. If they deserve a statue, so should Benedict Arnold.

Great point, Barry, and the perfect word.