Memphis in May International Festival has entered its fifth decade, and while its economic impact hits record levels, some important decisions loom in its future.

We’ve made no secret of our admiration for the way the festival’s president and CEO Jim Holt brought it back from the edge of bankruptcy when he was hired 19 years ago to a festival with today’s $112 million economic impact.

Without fanfare and shunning acclaim, he has guided the festival through a period characterized by escalating prices for music headliners, budgets shaken by bad weather, and ideas from the public that led to new events which lacked the attendance to make a profit.

When the first Memphis in May festival was held in 1977, it was an exercise in wishful thinking. The budget was $52,000 with events held in a downtown where the Chamber of Commerce was bankrupt, the Peabody Hotel was boarded up, Beale Street was abandoned, and businesses were closing their doors and hollowing out downtown’s economy – and hope.

By the time Mr. Holt was hired in 1998, downtown was showing signs of life but the festival’s assets were only $10,000. There were many who said it could not survive.

The Breakdown

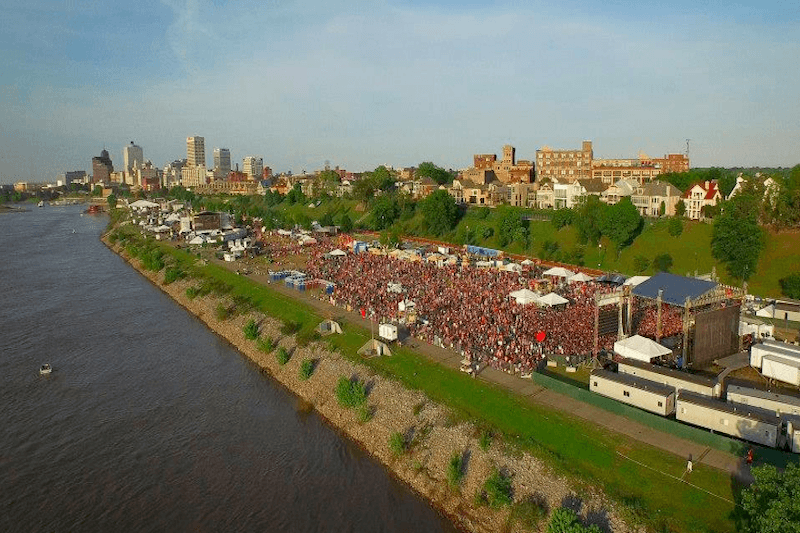

Today, the Memphis in May budget is just shy of $10 million a year and it brings 165,000 people to discover and rediscover Memphis’ first great place – its riverfront.

The individual breakdown of its $112 million economic impact is:

$55.7 million – Beale Street Music Festival (88,898 attendance)

$37.8 million – World Championship Barbecue Contest (63,721 attendance)

$18.2 million – Memphis in May annual operations

$184,814 – Great American River Run (3,730 attendance)

$172,709 – 901Fest (7,333 attendance)

Reflecting the festival’s strong national reputation, its two marquee events – music and barbecue – attract the majority of its attendees from outside Shelby County: 63% for the music festival and 56% for the barbecue contest. Out-of-county visitors had direct spending of $31 million for the Music Festival and $21 million for the Barbecue Contest.

New Rules

The popularity of the two prime events – the Music Festival was listed as one of the top 300 festivals in the world – suggest the long-term financial health of Memphis in May, but the changing dynamics of the music concert business in recent years, which have rocked promoters and venues across the U.S., have Memphis in May’s budget in its crosshairs. Despite that, ticket prices for the Music Festival remain lower than its peers.

The festival’s annual report suggests two things: 1) the music festival, once the cash cow and still drawing ticket holders from all 50 states and 14 foreign countries, today increasingly has less and less margin for error, and 2) the old adage that with good, warm weather, the festival would make meaningful money has given way to a new adage that says that it takes near perfect conditions to make some money.

The thinner margins for the Music Festival result from a harsh trend line: while revenues from the three days of concerts have doubled, the cost of talent has quadrupled. As a result, the Barbecue Contest now is a bigger profit maker than the Music Festival.

It’s produces a telling equation: the $112 million in economic impact produces $3 million in local tax revenues and international publicity for Memphis, and yet, Memphis in May itself netted a mere $278,655.

The Big Question

Speaking of publicity, the Kings of Leon performance was captured by a 14-camera, more than 50 person crew for PBS’s series, Landmarks Live in Concert. For the program, the band insisted on their Beale Street Music Festival concert being featured and described it as fulfillment of their adolescent dreams of headlining the Festival.

All this is context, and it positions Memphis in May clearly at a crossroads, chiefly, does it continue its international theme which is its distinctiveness or does it abandon it in the interest of financial prudence and as a result of the realities of a digital world.

In the past three years, the average amount spent on the Festival’s international agenda, including performers and educational programming, has been $3.2 million. Clearly, the elimination of the international component of the festival would make the annual budget puzzle much easier to put together.

That said, there is already a groundswell for the festival to abandon its international moniker for 2019. That’s the year of Memphis’ bicentennial and there are many who advocate that in that year, the festival should celebrate the city itself.

Right Sizing

That’s not as simple as it sounds. After all, several times over the years, Memphis in May created city-centric events, most recently 901Fest, but they have had trouble finding an audience and producing enough revenue to keep them alive. That’s why there is no longer a Memphis food festival or children’s festival.

It suggests that if 2019 is to be a year that spotlights Memphis, the challenge for the festival is to develop an event with the size and scope to take its place beside the Music Festival and Barbecue Contest as a major draw.

It is not without risk. The last big idea was the Memphis Tattoo. Modeled after the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo in which military bands and artistic performances perform on the esplanade of Edinburgh Castle in Scotland, its losses almost sank Memphis in May.

Beyond the Memphis focus for the bicentennial, it speaks to a broader, more fundamental question: should Memphis in May eliminate international altogether?

There is no argument that the festival’s association with an honored country each year has been a benefit for Memphis. It began at a time when the Memphis economy was sluggish and relationships between the city and international companies was few and far between. Coupled with Memphis in May’s tribute to Japan in its first festival and then-Governor Lamar Alexander’s courtship of Japanese investment, within a few years, Memphis led the state in the number of Japanese businesses here.

A Simpler Time

It was a time when there was no Internet, a few university courses in international business, and Memphis was at the bottom of the 50 largest MSAs in the percentage of its population who had traveled internationally. It also seems that foreign countries back then were more interested in educating American cities about their culture and economic opportunities, but today, many countries offer only meager help.

It is not easy to determine the impact that exposure to three dozen different countries have had on Memphis since the beginning of Memphis in May, particularly as it relates to the curriculum for each country that was used by area students. It meant that students learned about 12 countries by the time they graduated from high school, expanding their understanding of the world and its cultures.

However, today, there is no lack of information. Not only are there tens of thousands of websites for every country, but today, if we are interested in another country, we can even walk the streets of its cities with Google Earth.

We can make an argument for retaining the international connection or eliminating it altogether, but the lesson of 40 years of experience at Memphis in May is that whatever the final decision, the board should remain flexible and be ready to adjust as the results of its decision unfolds.

For the rest of us, we need to remember that while Memphis in May International Festival soldiers on, the battlefield is littered by similar events, particularly music festivals, that have been given up for dead in places. Among these are cities near us like Nashville, Little Rock, Birmingham, and Mobile.

It’s easy to take Memphis in May for granted but it’s an anchor event in our community’s civic life and every one of us should stand with it as it prepares for the future.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

The Memphis in May festival is showing its age and some changes are needed. It’s problem stems from competition from all types of music festivals taking place all over. Big corporates like Live Nation now totally control this segment of the entertainment industry and they set the acts and finances for all types of entertainment. MIM is now very small potatoes—almost a niche local event, certainly not like big league like Coachella or Bonaroo. The recent crowd numbers have not been impressive and Memphis looses out on the top tier music acts. In conjunction with the BBQ contest, MIM is more like a small city carnival without the midway. The organizers should it evolve naturally. Memphis in a May will never be much more than it is right now.

Haven’t attended the last few years but the many rain soaked festivals with storms and nasty deep mud everywhere do not make us yearn for a repeat visit. While it can be nice being on the river if weather cooperates, overall access and amenities are poor. Our kids used to go but they now deem the event and the music acts as “lame”

Live Nation is driving up costs which is why Memphis festivals in so many cities are folding. The music festival continues to get good acts considering that its budget is lower than all the gigantic events you mentioned – there’s a reason there are only a handful of those kinds of events.

The lineup this year was widely approved of and Memphis in May’s system for listening to community input about who to gook seems to be paying off.

It’s pretty silly to compare the music festival to Coachella and Bonnaroo even though they attract just barely more people than ours. The budgets are many times bigger and so is their ticket prices, which is why fans are complaining that they are being priced out of going and why attendance for the big boys is down.

We could learn a lot from Nashville where enormous crowds gather all over their downtown for the CMA festival every June. Nashville now has some of the largest crowds and biggest fireworks displays and concerts in the US for July 4th and for New Years Eve. All of those are far larger events with much greater economic impact than Memphis in May.

Also Nashville has the new Ascend Ampitheatre on its downtown riverfront snd the acts there are booked by Live Nation except for the outdoor concerts by the Nashville Symphony. Interesting too that Franklin now hosts the annual Pilgrimage Music Festival. This year Justin Timberlake headlined and invested in it. JT has built a huge mansion in Williamson County plus a home nearby for his parents.

We’re now in apples and oranges territory. It’s not Memphis in May’s job to build downtown amphitheater or fireworks displays for fourth of July. We definitely need higher expectations by city government, our arena, etc. I liked that Franklin lineup but it still sells only one-third number of tickets as Music Festival here.

And I’m already tired of JT cozying up to Nashville.

Just noticing there were 7 comments on the article before reading it I was curious with what this was about how anyone could start comparing it to Nashville in some way to make us look inferior– sure enough as always there was some comparison virtually out of nowhere!

Maybe it was mentioned because Nashville was referred to in the article. Memphians need to get over the envy of all things concerning Nashville. We all know that Nashville eclipsed Memphis a long time ago.

well just because Gnashville gets Jimmy Buffett for New Years Eve and we get a gun show at the agricenter is no reason to diss on Nashville…

wait….

Anonymous you used the term “Gnashville”. That is a term some people from Nashville use to reference their hockey team. Are you from Nashville?

We should go back to calling it “Cotton Carnival”