Walker Percy said that the problem with culture is that we must wrest meaning from experiences that come to us prepackaged and disconnected from our own assumptions and expectations.

Consumers today are being pulled in a multitude of directions by entertainment options that are increasing exponentially. More and more, people want what they want when they want it and where they are.

Trends in arts and culture are like those in business. More and more, success is found by going large or with a smaller distinctive niche. The ones in the middle are under the greatest stress.

These and other trends are why arts and culture groups are challenged today to increase attendance – and revenues. The world often seems to be rushing to places that make it harder and harder to achieve the impact and to attract the people they need to reach for higher ambitions.

No Better Time Than The Present

It’s also why it makes sense now for Memphis Brooks Museum of Art to determine if another location gives it the opportunity to a higher profile, to more paying customers, and to explore more effective ways for outreach and programming. After all, the museum has been talking – complaining – for 15 years about its building and the barriers it creates for the museum’s success, so for us, it seems like now – a time of increased momentum and self-confidence in Memphis – is the perfect time to consider what it would take to elevate the art museum to a higher tier and higher stature.

Regardless of the ultimate decision, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, at the end of its deliberations, must feel that they are no longer prisoners of a building, and instead, that its building contributes to its overriding purpose, which is not to preserve its shell but to operate a nationally important art museum.

In addition, when a totally new museum would cost approximately $84 million and that’s basically the cost of expanding by replacing the 1973 building and increasing parking, it’s only logical and responsible in their fiduciary roles.

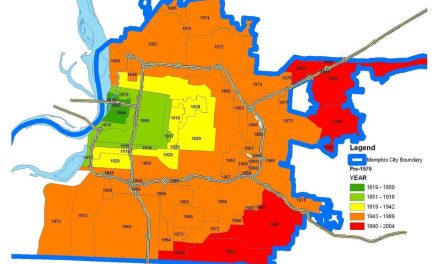

The museum was placed in its Overton Park location at a time when many city art museums were made major tenants of major city parks. When the building in Memphis was opened in 1916, it had no art collection, staff, or exhibit schedule. The city limits were just barely east of East Parkway, and the zoo had little more than a bear and an elephant.

Trying To Make It Right

The building’s architect was James Gamble Rogers, who was chosen as a result of his impressive designs of the Shelby County Courthouse and the Goodwyn Institute Building which both opened in 1909. In the years following his work in Memphis, he would essentially become the architect on almost every building for Yale University from 1924 to 1935.

Mr. Rogers’ building for the nascent art museum was named for the benefactor, Bessie Vance Brooks, who chose the architect, paid $115,000 for its construction, and donated it to the City of Memphis. The building was a white marble garden pavilion, inspired partly by the Morgan Library in his hometown of New York City, and by the sixteenth century Villa Giulia in Rome, and when it opened, it was called the Brooks Memorial Gallery of Art.

In 1955, the museum cut the ribbon on a $250,000 addition designed by Memphis architect Everett Woods, and in 1973, the $650,000 Brutalist addition designed by Jones and Mah was added. The 1955 addition was demolished for a $6.5 million Post-Modernist addition when Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill was hired in 1986 and the museum got a new entry rotunda, restaurant, gift shop, lecture theater, new galleries, and collection storage.

In other words, it seems to Baby Boomers that for much of their lives, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art has been trying its best to make do with a location that was chosen for it about 60 years earlier, and with 8,000 artworks that cannot always be kept in the environment needed for their protection, the cost of dealing with the increasingly inefficient building demands the analysis of options for the future.

Considerations

There are things that have to be considered: (1) most of the major benefactors to the museum live in East Memphis, and (2) the building and the bulk of the art collection acquired before 1989 are owned by City of Memphis (the museum took its present name in 1989 and became a private institution).

There will undoubtedly be some who call for the museum to remain where it is for sentimental or historic preservation reasons, but surely the building is not at risk. Surely no one has the gall to suggest tearing down the building, especially the part built in 1916.

Besides the problems caused by the building itself, it is inarguable that the museum and all of Overton Park has a parking problem, and with the continued, inspired work of the Overton Park Conservancy, it will only become a more pressing issue. Best of all, the Conservancy has put an emphasis on diversity that is improving a sense of ownership for a generation of African Americans who could only visit Overton Park on Thursdays. As the Conservancy continues to mature, there will undoubtedly be more activities and events.

In other words, the parking is only going to get worse.

But we digress.

Location, Location, Location

Here’s the most pivotal metric for us: with around 85,000 visitors a year and an annual budget of $4.7 million, the per capita cost is $55. Admission tickets are $7. The museum has 2,500 memberships, and the cost is $50 for individuals, $65 for families, and $150 for “advocates.”

That’s not an unusual balance sheet for arts and cultural organizations in Memphis, but it leads to the inevitable questions: can a different location increase attendance and memberships, leading to more revenues to support bolder aspirations for the art museum? Does it make more sense to go to where the public?

It’s a question being asked in a number of art museums across the U.S., and the answer has often been to move downtown. It’s a strategy to move to where the most people are, and the Memphis Convention & Visitors Bureau has long said that it seems that everyone who comes to Memphis as part of the city’s $3.2 billion tourism industrial eventually finds their way to the river’s edge.

More to the point, when – there should be no “if” – Memphis follows through with the exciting plans for the riverfront unveiled by Studio Gang for the mayor’s riverfront task force, it becomes a magnet for more Memphians to enjoy a variety of activities in an interconnected necklace of parks and special places. That too is another reason for downtown to receive serious consideration.

There, it is possible for the museum – enhanced by the confluence by art and architecture – to command an iconic presence on the bluffs. It is possible to imagine the kind of spectacular architecture that would attract more national attention to a museum building that would speak more accurately to the museum’s DNA and to its determination to aim for great things in the future.

As the indispensable 9:01 Commercial Appeal columnist Chris Herrington wrote Friday: “If you read the fine print in the Memphis Riverfront Concept presented by design firm Studio Gang earlier this summer, in the ‘Fourth Bluff’ section, you’ll see – Convert Parking to Cultural Asset – replace the parking garage at Front and Monroe with a new cultural amenity that can replace the parking garage at Front and Monroe with a new cultural amenity that can anchor the corner and spill activity outdoors.”

Orlando’s Case Study

In Orlando, the Museum of Art has outgrown its current location in Loch Haven Park, and it is looking for a site where it could increase its current 19,000 square feet of exhibition space to 50,000 square feet, a bar and a café, a glass-blowing school, and a five-star restaurant experience.

Its plan, Forward to 100: Reimagining the Orlando Museum of Art in the 21st Century, was aimed at increasing attendance from 60,000 (just over half are paid admissions) and revenues. Its budget is $3 million a year. The 15 peer cities listed in the plan have average attendance of 356,000 and an operating budget of $6.25 million.

“Against this backdrop, we ask what is the best strategy to attract a much larger audience and increase the operating budget…to make Orlando Museum of Art a much more compelling offering? What are the factors that attract the number of visitors, the level of giving, and overall economic support of Orlando Museum of Art? What are the present and future trends that dictate what the museum should aspire to.

“…Think about what a 21 century museum should be. Make sure that it is always welcoming and available for events and programs that might not be directly to the Orlando Museum of Art offerings but nonetheless allow continued and enhanced explore to the community at large. Make it comfortable. Can people meet and talk? Can they feel comfortable being there without the necessity of viewing the art or participating in the programs underway? This is the public square in which the great expressions of man’s creativity…are specifically enjoyed through study and observation or simply by virtue as the setting for other activities.

“So what does it all mean? It means that we accept the notion that to maximize the potential of Orlando Museum of Art, a new container is needed…it is essential that we seek to become an integrated part of the urban fabric that is Orlando….We are persuaded that if Orlando Museum of Art is to be the museum of the 21st century, it cannot be optimized around a single use but must be integrated into an urban space that works on multiple levels and delivers on a myriad of needs.”

In answering these questions, the museum’s board voted to move downtown.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

Our downtown is in fact on the western edge of the city, and parking there is already difficult, especially at the times other things are going on – which is the time museum openings and events would happen.

Destroy an old parking garage?! Brilliant! less parking!

Being in that locale puts the emphasis on looking at the river, and sunsets, not on the very cool Brooks permanent collection.

The true heart of the city, I am afraid, is Poplar-Perkins.

There is too much parking downtown already. We go to other cities and walk blocks to see something of interest, but here at home, we expect to park at the front door every time.

But, there is the opportunity to replace a delapidated garage with new parking with a green roof.

Hopefully, there is not an option that is east of East Parkway although we could get interesting in a Broad Avenue location.

Thanks for comment, Dan.

Forget out east – purchase the Commercial Appeal’s building on Union Ave. and put it there. That part of downtown seriously needs an upgrade and the museum would really improve it and be located in a high visibility location.

Brooks is nice but definitely not a world class art gallery. The facilities badly need to be improved. While the $7 admission is reasonable it’s never been crowded when I visited which tells me a lot about the local market and their marketing or lack thereof. Moving downtown or out east would be a huge mistake. Parking is terrible as it is everywhere nearby near the park.

You say Brooks has 85,000 visitors a year, and the CVB says, “… that it seems that everyone who comes to Memphis as part of the city’s $3.2 billion tourism industrial eventually finds their way to the river’s edge.” Well, the CVB also says that 1,000,000 people (plus) visit the Zoo annually……less than a football field away is Brooks. hmmmm.

Orlando is a totally different beast and has no place in the discussion.

If, Brooks wanted a Brooks ll, then perhaps a downtown location would be desirable. I can’t help but wonder what exhibits would fill the year with showings, that are apparently not available now?

You mention the “parking garage”…That’s getting close to the public promenade, isn’t it? However, the only other place that’s left on the Bluff would be the Carlyle properties, and with all they have been given, and all the demolition on the Bluff, and still no announced Plan with a start date, they are probably salivating for it.

Sorry, but this may be the worst defense for Brooks leaving Overton Park, and especially from Smart City. I’m disappointed.

Memphis has 10 million visitors a year and CVB is right, they all go to the riverfront.

Also, if you just want to take one million at zoo and suggest that is primary market for Brooks, at this time, the museum is attracting about 8% of that total, which suggests to us that they have different markets.

We didn’t say Brooks should leave Overton Park. We said that the board members must exercise their fiduciary responsibilities and consider what they can do to attract more visitors and increase revenues. That’s not happened at the park for decades, so they are right to consider their options. Museums all over the U.S. are moving because no museum should be a prisoner of its building or its location.

As for the public promenade, there are already two garages on the public promenade, and either of them could be replaced with better garages with a green roof.

You sound like you are clinging to a past that hasn’t served the museum well. Whether they remain where they are or move, they absolutely have to attract more paying guests – to have fewer than 100,000 visitors is a disaster as proven by average attendance at comparable art museums.

Finally, have you ever been to downtown Orlando, not the tourist district, but downtown? It is much more comparable than you are aware.